AROUND THE WORLD

Anti-submarine Indicator Loop stations in the United States

Peaks Island/Fort Elizabeth, Maine

Drawing by Gerry Butler

This report draws heavily on a review of station logs and war diaries for Naval Unit 1F (Peaks Island and Fort Williams) made by Dave Pierson at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Trapelo Road, Waltham, Massachusetts. These logs and diaries were handwritten and typically cover two to three days per page. They were all stamped 'secret' but are now declassified. The other Naval Units' records await a later trip to Waltham.

|

If you worked there or have any feedback please email me: Dr Richard Walding Research Fellow - School of Science Griffith University Brisbane, Australia Email: waldingr49@gmail.com |

LINKS TO RELATED PAGES:

Indicator Loops - an overview (YouTube, 70 minutes)

WW2 comes to Casco Bay

The United States entered the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. The next day, the old coast defense guns at Fort Williams in Cape Elizabeth, Casco Bay, Maine were test fired. The concussion of the firing blew the doors out of four recently constructed garages near the battery. The Coast Artillery quickly moved out its mobile artillery to Biddeford Pool and Popham Beach to temporarily extend the defenses of the harbor. By April 1942, the US Navy installed anti-submarine nets and the highly secret anti-submarine indicator loops at all the entrances to the harbor (the indicator loop technology was developed by the Royal Navy in WWI and modified by the USN in the 1930s to suit local needs). The Coast Artillery planted mine fields in the main channels into Portland Harbor. Coast Guard patrolled the waterfront, and troops were sent to Maine to guard vital highway and railroad bridges, such as the Grand Trunk Railroad bridge at Yarmouth Junction. The Navy was a popular branch of the service in Maine, and a mass enlistment in Navy took place in Portland June 7, 1942.

Peaks Island/Fort Williams Loop Station

The following gives some of the day-to-day details at Peaks Island and Fort Williams loop stations from 1942 to 1944. This information has been extracted from the Waltham, Massachusetts archives by Dave Pierson.

In April 1942 a site was selected

for the station. Possible sites included Fort Williams, "Smiths" on Peaks

Island; the 8th Maine Regimental Property (on Peaks); the Smith

House opposite head of beach, 600 feet from tail cables; the knoll to

the east; west end of beach - 800 feet to tail cables. The USN decided

against Fort Williams for several reasons, notably - because of the greater

distance to the loops and tails; the need to add extra 'tails', the proximity

to the heavy gun emplacements (vibrations upset galvanometers); and the

risk of damage to the landing tails by the rocky shore. Eventually, the

Peak Island site was chosen - a cottage about 1 mile from the gun emplacements.

A quick lick of paint and then they moved in. The officers were stationed

in luxury at Oak Cottage, about 1¼ miles from the loop station.

|

|

Submarine cable located in Casco Bay - supplied by Chris Whalen (email: Whalenolder@aol.com). Chris operates a salvage business along the coast of Maine and has recovered some submarine cables from Casco Bay. His company, Coastal Reclaim, LLC salvages abandoned utility wires that riddle the mid-East Coast ocean floor, as well as lighthouse cables that are obsolete due to solar technology. |

|

|

|

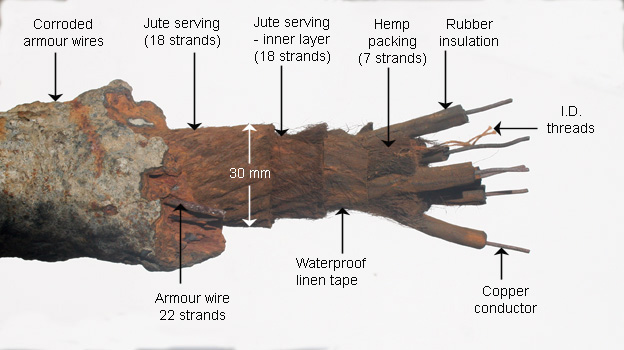

The cable shown in these four photos is a 6 conductor #16 gauge, rubber insulated, jute, armored cable. It was located at N43° 44.859, W70° 00.082 running parallel to the shore, but is yet to be confirmed as indicator loop tail cable. |

|

|

|

Chris Whalen sent me the Boston cables to Australia where I examined them more closely. The six cores and the copper conductors can be seen clearly, as can the remains of the steel armour wires. |

The hemp serving can be seen in this close-up. It helps with flexibility and protects the rubber insulation. |

|

A longitudinal section of the cable. The outer armour wires are badly corroded from 60 years in a salty environment. The original diameter was about 40mm (1.6 inches) assuming there was an outer waterproofing covering of tarred jute. The steel armour wires are 2.5 mm diameter (10 gauge AWG) protect two layers of jute, each wound clockwise and consisting of 18 strands. Under these is a waterproof linen tape which surrounds the six cores of the cable. Each core consists of a tinned copper conductor of 1.3 mm diameter (16 gauge AWG) insulated with a rubber sheath of 5 mm diameter. The cores are protected and separated by seven strands of hemp packing. There is also a twin white thread enclosed with the cores - possibly an identification thread. To gat a sense of the scale I have shown the diameter of the outer jute serving as 30 mm. This cable is quite possibly a indicator loop tail cable. Cables from other harbor defenses around the world can be see at my Cablemakers website. |

Two loops - initially called 1 and 2 - were laid by the army. As they had cable laying ships for the controlled minefields in the area, this proved ideal. These loops were soon renamed Affirm (Loop A) and Baker (Loop B) (see map above). They were both of the three-legged design (see Indicator Loop technical page for details). Affirm consisted of three 3000 yard legs, spaced 120 yards apart (3000, 120 + 120); Baker was a 4000, 160 + 160 loop arrangement. Both were in water 15 fathoms deep. The tails were connected to the loop station on 21st April 1942.

A week later (27 April) the electrical equipment was installed in the loop room. It consisted of General Electric Flux Meters (galvanometers) and a teletype machine. Testing then began. What appears to be the first magnetic signature recorded was that of the 37,000 ton battleship USS North Carolina, just before she headed off to the Atlantic to defend convoys against the German battleship Tirpitz. Signatures of a cruiser and an aircraft carrier were recorded and all were mounted on cards for reference and training purposes (see below).

Two Lights to Baileys Island Loops

An outer ring of five loops was established

from Bailey's Island to Two Lights.

The northern section comprised three loops - C (4000 yds), D (4200 yds) and

E (6000 yds) and connected to a receiving station on Baileys.

The southern section consisted of two loops - F (6600 yds) and G (7000 yds)

connected to a loop station at "Two Lights" (lighthouses). This gave some localization of

the contact, and matched the capabilities of the loop technology.

Taken together these gave an inner

ring (A, B) of loops from Fort Williams to Peaks Island to Long Island, and an

outer ring from Two Lights to Bailey's Island (C, D, E, F, G). The inner ring was

also fitted with moored and radio linked-moored hydrophones. All

other navigable passages into Portland Harbor were closed with Anti Submarine

Nets for the duration of WWII.

|

|

USS New Jersey |

Loop signature record |

Loop signature record

This recording was made by seaman S. Handler

at the Fort Williams Loop Receiving Station on 20th December

1943 when USS New Jersey, (shown above), under the command of Capt.

Carl Holden, made an inward crossing of Able Loop at 11.52 am. Visibility

was high that morning (10 mi). The galvanometer being used was the GE Type

OS-2, Serial No. #19, set at a shunt ratio of 125:1 and the sensitivity

control set at zero. An injected voltage of 0.06 V to the Right was used

for centering. The graph has the characteristic pattern of two crests and

one trough, with the trough height (31 "lines" of flux) about twice that

of the crests (18 "lines"). A "line" of flux is determined by the sensitivity

control setting on the amplifier. In this case, the setting was zero which

meant the sensitivity was left at it's base rate of 1000 lines per mm.

The peak-to-peak distance is 18 + 31 (= 49 lines) which corresponds to

49000 Maxwells of magnetic flux linkage. This can give operators a idea

of the size of the boat. For example, a 250 ton undegaussed U-Boat has

a magnetic flux of 40000 Maxwells at 10 fathoms at this latitude. The speed

can be calculated from the vertical lines (1 cm apart) and 1 cm = 1 minute.

From start to finish took the 888 ft long USS New Jersey six minutes

which corresponds to about 1.5 knots, assuming the loops are each 150 yards

wide. Two weeks later, New Jersey headed off to it's first naval

engagement - in the Pacific Theatre.

|

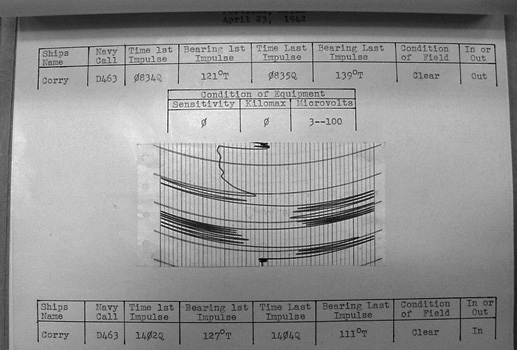

This chart shows the signature of DD463 USS Corry April 23, 1942, as she passed over one of the Portland loops. She was later the US Navy's only major loss on D-Day. (Martin Dwyer, copied from Waltham Archives in Massachusetts). The interpretation of the signature and some more examples can be found at: Reading Loop Signatures. |

Staffing

In mid-May (1942), six men arrived at the station to begin duties. The USN believed that one man was sufficient per four-hour shift as there was little traffic over the loops. Six raincoats were ordered (one mile to the barracks) and typhoid shots were given all round. The first bit of excitement was on the 11th May when a crossing was recorded in thick fog where no visual sighting could be made. The second was three weeks later (3rd June) when the station went on submarine alert. But it was just a false crossing caused by interference. To top it off, that afternoon a bottle of mucilage and a stapler were received in good condition, followed soon after by two pistols, holsters and 144 cartridges. But it wasn't all take - there was give. Three left-over cans of Benjamin Moore paint were given back and the army carried them away.

More problems

By 1st June 1942, the operators were still having difficulty with signals from Baker and one of the operators tinkered with it to get it working. The repairman warned the operators "don't do that". However, both recorders still proved erratic. Whenever the bay was swept for mines the recorders were disconnected so as not to blow their fuses. On June 22, 1942 a German U-Boat was suspected of making an inward crossing but due to faults in the other loop, it was not detected on its way out. The fault turned out to be from a loose terminals due to the continual doing/undoing so on the 27th July (1942) a knife switch was installed. A litany of other problems were reported – paper jams in recorders, all three recorders unsatisfactory, sensitivity problems with galvanometers, telephone problems, teletype line down, clock not working. One fluxmeter - the OS-50 - was found to have a resistor in the amplifying circuit that heated up causing unsteadiness in the recorder preventing the needle from centering. The flux meters used were labelled OS-02-09 (on Able), OS-0-51 (on Baker). OS-50 became the spare. The amplifier attenuation settings were usually 1:1 or 1:5. In cases where sensitivity was low (from a weak signal), the ratio was changed to 1:125.

On September 22nd, the station was officially changed in status from Naval Signal Station No. 6 to a loop receiving station (USN LRS). All of the signaling equipment thus had to be returned. This included 150 flags, one 12" searchlight, one rheostat and one typewriter. In return, four rifles were sent over to be "left loaded in strategic positions" near the loop station and the petty officer was henceforth required to carry a pistol.

Shift to Fort Williams

The first repairs to the cables

were made on 26th October. A break was found in the centre leg

of Affirm and when this was repaired and relaid, the recordings improved.

However, the army blasting continued, and the loop operators had to keep

turning the flux meters off. This was hardly good harbor defence so the

USN decided to relocate the loop station to Fort Williams. On 9th November, USCG Pequot spliced the tail cables to the new location. Mr Simpson

and Lt Sigafoos from BuShips (Bureau of Ships) inspected the station and

approved it as ready for the grand opening. The new loop room was 8' square

– hardly enough to swing a cat. Seven men were stationed there.

By 8th December the Navy decided that the cables were not functioning properly and relaid Affirm with 'slack lay' to reduce the pertubations caused from laying a cable too taut. The following lengths of Type 111 cable (in yards) were added to the cables: Affirm – inner 135, middle 300, outer 450. To Baker, 150, 135, 135 was added respectively. This seemed to improve sensitivity and they were now getting between 200 lines (Affirm) and 400 lines (Baker) although magnetic interference from minesweepers (up to 8 miles away) was creating havoc particularly with Baker's recorders. Interference continued to be a source of problems at the start of 1943. Affirm was recovered and relaid nearby as loop 'Able'. The army cables near Baker's tail cable made balancing (centring) difficult. Various transmitters - such as those of the Harbor Entrance Control Post produced continual interference particularly on the 2150 kHz frequency. This caused fuses to blow in the resistor balancing box. On April 3rd 1943, representatives of the NLDF (?) found that the public power supply was improperly grounded and fixed that easily. However all they could do about electrical storms and the Northern Lights was to install double pole, double throw switches. This seemed to do the trick. Things were looking up - the American Legion sent over a gift of 31 phonograph records.

Monthly reports

They were now recording monthly

crossings of about 365 ships across Able and 37 over Baker. Also done monthly

were loop resistance checks. The resistance - in ohms - were as follows:

Loop Able B-R 19.71, B-W 19.18, R-W 19.84; Loop Baker 28.03, 27.79, 27.63.

Recall that Baker loop was about 1/3 longer than Able, hence the increased

resistance. The sensitivity readings varied between 77 and 240 for Able

and 164 to 455 for Baker which were quite acceptable and gave good, clear

signatures. As usual, all recordings were burnt at the end of each month

(i.e. March recordings burnt at the end of May).

Severe magnetic disturbances continued to cause problems at all stations. A comparison of signatures between Fort Williams, Bailey Island and Cape Elizabeth during mid to late 1944 confirmed that atmospheric disturbances were to blame. But by then, it didn't matter much.

On July 5, 1944, U-233, a German Type-X1B minelayer (90 m long) was sunk by aircraft and USN destroyer escorts USS Baker and USS Thomas after a 9 minute battle. It crawled its way 100 miles down the coast and entered Casco Bay where it finally sank. However, no loop recording was made. As the threat from German U-Boats waned, the loop stations were gradually wound down. What remains of them today is not known. But we're trying to find out. If you have any idea, please contact Richard Walding

Recovering the cables after the war

I had an interesting comment from Nelson Barter from South Harpswell, Maine (24 Nov 2010):

"When I was a teenager I worked in the lobstering industry (as that was the only way to make any money here); when working on boats owned by some of the locals that were here during the war I always enjoyed hearing their stories. Bill Henry Bibber was a colorful older gentleman and local fisherman/boat builder who told me a story about working after the war for the Navy, salvaging anti-submarine cables. He said that there was a huge pneumatic circular saw with a metal cutting blade on board. They would cut the cables into ten foot lengths and stack them on deck. It was grueling work; he marveled that the cables were so heavy to the foot. He described them as lead shielded on the outer layer which explained the weight".

SOURCE MATERIAL

NARA Naval Records

National Archives and Records Administration Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments (Record Group 181) 1784-0981

- 181.15.22 Records of Naval Unit 1-A (Loop Receiving Station, Bailey Isle, ME)

- 181.15.23 Records of Naval Unit 1-B

(Loop Receiving Station, South Portland, ME)

- 181.15.24 Records of Naval Unit 1-F (Loop Receiving Station, Fort Williams, ME)

- 181.15.25 Records of Naval Unit 1-I (Loop Receiving Station, Westport Point, MA)

* Text reference in paragraph 1:

Butler, Gerald (2000). The Military History of Boston's Harbor Islands. Arcadia Publishing, 2 Cumberland St Charleston, SC 29401 USA. 128 pages,

cost US$17 + US$9 p&h (overseas). Email: sales@arcadiapublishing.com.

Web address www.arcadiapublishing.com.

A fascinating book - 250 photos from 1860 onwards.

OUR THANK YOU I appreciate the assistance of the NARA archivists in making the Naval Unit files available for review.

Additional information, including a chart

fo the loop locations, may be found in:

Portland Head Light

and Fort Williams

Kenneth E Thompson Jr

The Thompson Group

55 Vannah Ave

PO Box 3897

Portland, ME

04104

And from the Gift Shop at

Portland Head Light Museum

Cape Elizabeth,

ME

SOME USN INDICATOR LOOP LINKS