|

|

|

|

| The Men | The Spirit | The Ship | The Mission |

|

|

|

|

| The Men | The Spirit | The Ship | The Mission |

USCG CABLE SHIP PEQUOT - UNITED STATES

HARBOR DEFENCES

OUR SAILORS' STORIES

This page tells another one the stories of the sailors who served

aboard the U.S. Coast Guard

Cable ship Pequot during World War II. The Pequot served as a harbor defense

cable-laying and repair ship under direction of the US Navy. Her full story

can be found on the Pequot Home Page.

Seaman Mike Luongo has contributed extensively to the Pequot

website project and donated numerous photographs. In addition to providing us

with his biography, in February of 2010 he was interviewed at length by

Pequot researcher Chip Calamaio about life aboard the Pequot. Much of

that information is included in his story. All images courtesy

of the Luongo family unless otherwise indicated.

THE MIKE LUONGO STORY

|

|

|

|

|

Seaman 1st Class Mike Luongo in his dress blue uniform. |

||

Michael “Mike” Luongo was born on July 10, 1922 in Newark, New Jersey. He was raised in the neighboring town of Belleville. Before the war he worked for a company that made fuel lines for heavy construction equipment. In 1942 after World War II broke out Mike enlisted in the Coast Guard to serve his country when he was 20 years old. Like a lot of his Pequot shipmates he went through basic training in Manhattan Beach, New York.

|

|

| Like these recruits and many of his Pequot shipmates Mike when through Coast Guard basic training at Manhattan Beach Training Station in New York. (USCG & Library of Congress Photos) | |

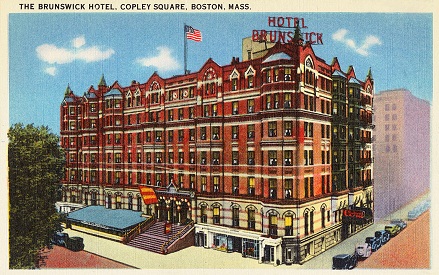

“There were about ten thousand recruits in there with me,” Mike tells us. “They organized us into different details. They got us up at 5 am and we trained until 10 pm every night. I heard that due to the war they’d taken 6 months of training and squeezed it down to a few weeks.” Once he finished basic training Mike went to fire fighting school in Boston. “After I finished basic training and fire fighting school I was in a big hotel in Boston that the Coast Guard used as a receiving station.

|

|

The Brunswick Hotel in Boston was taken over by the government and used by the US Coast Guard to house sailors between duty assignments out of the Boston District. (vintage postcard Boston Public Library Collection) |

I was with a group of about 10 guys and we were supposed to ship out on one of the big Coast Guard cutters but it never came into port. The story was that it had just sunk four German subs and then rammed a 5th one so it was laid up in Nova Scotia for repairs.”

Instead Mike was sent to the Coast Guard Station in Portland, Maine where he served under the "Captain of the Port" command (COTP). He was assigned to port security duty along the docks to guard the piers. This was during the height of the Battle of the Atlantic when many Coast Guard Cutters and Navy escort ships were based out of Portland during convoy escort duty and fierce battles with German U-boats.

|

|

|

Mike patrolled the docks and piers during his duty assignment with the Captain of the Port command at the Portland Maine Naval Base (Naval Historical Center & USCG Photo) |

|

Next Mike was sent to gunnery school at the US Naval Training Station in Newport, Rhode Island. “We were given instruction on the 20mm and 40mm anti-aircraft guns along with the 3 inch 50 caliber deck gun,” Mike explains. “They divided us into groups and we had competitions shooting at sleeves towed behind airplanes.

|

|

| The anti-aircraft Gunnery Training Center Mike attended at Prices Neck on Newport Rhode Island’s Ocean Drive. During November 1943 alone over 14,000 sailors went through the school. (Naval War College Museum) | A WASP A-24 dive bomber towing a gunnery target. Mike and other seamen practiced their anti-aircraft marksmanship during live fire practice by shooting at these airborne target sleeves. We assume the tow cable was much longer! |

The platforms the guns we were shooting from were platforms that moved to simulate being on the deck of a ship. We practiced with tracer rounds at night using special red goggles. They also had us take firearms apart and put them back together again in the dark.”

|

|

| Mike trained on the 20mm and 40mm with tracer rounds at night using Variable Density Goggles like these. We have records of Captain Sande ordering these same goggles for the Pequot crew. (usmilitariaforum.com) | USCG Sailor James A. Flathery on a 20mm using the revolutionary Mark 14 gun sight that Mike Luongo trained with. This sight was never issued for the Oerlikons aboard the Pequot. (USCG Photo) |

Mike was also trained in the use of

the newly developed Mark 14 gun sight for the 20mm Oerlikon and

40mm anti-aircraft guns. “That sight would give you the distance

to the target and figure out the speed of the airplane you were

trying to hit and determine your lead firing distance. It was

really great but for some reason we never did get those for our

20mm guns on the Pequot,” Mike adds.

LIFE ON THE PEQUOT

In the spring of 1943 Mike received orders to ship aboard the Pequot where he served as a Seaman 1st class until his discharge after the war. “What I liked about Pequot duty is that we made port at Staten Island a lot. So I could take the ferry and subway to Jersey and spend a lot of time at home compared to the other guys,” he remembers. “My family lived only about 9 miles away, close to Giant stadium, so I could easily go home when I wasn’t on duty, and my girlfriend, Lee lived only two blocks away!”

|

|

|

The Polo Grounds was the home to the New York Giants in the neighborhood where Mike Luongo grew up and where he would spend time on liberty when the Pequot was in the New York area. Photo left: footballforum.com; right (Photo Air Edited ++) |

|

“That first night aboard ship when I went to turn in was the only time I really got scared,” Mike admits. “I was lying there and everybody had a life jacket right where you slept and attached to the life jacket was a flashlight and whistle. Yea. I was more scarred than anything else. After that I didn’t have a hard time sleeping at all , except when some guys would come back from port drunk and wake everybody up.”

|

|

|

Coast Guards sailors wearing the standard issue “Kapok” life vest that Mike wore aboard Pequot. An emergency locator light could be tied on up near the collar. (USCG Photo), (usmilitariaforum.com) |

|

When examining our 1909 deck plans of the Pequot when it was first constructed as an Army mine planter, Mike said some things were very different by the 1940s. “We had a laundry room and there was one big head with rows of commodes and sinks and lots of shower heads. The fresh water came from a coated tank and bilge water was used for the showers” Mike remembers the Pequot had one large galley that ran across the ship and the large aft cabin on the main deck was the crew’s mess hall. "The mess served as the crew's meeting place," he recalls. “We had coffee available 24/7 and a radio was on all the time. In the evenings we would write letters, play cribbage, talk, or play cards. They kept the government radio station on so we’d get war news. I also remember sitting back there and listening to broadcasts of the World Series.

|

|

|

During batting practice before game one of

the 1943 World Series four B-17 bombers dropped down out

of the sky and buzzed Yankee Stadium clearing the

flagpoles by about 25 feet. Many, including the radio

announcer, thought the flyover was all part of the show,

but the four air crews on their way to England who pulled

the spontaneous stunt were arrested when they landed in

Maine that afternoon. Rather than court martial and lose

valuable air crews at a critical time in the war they were

given letters of reprimand and fined $75 each. An Air

Force General told the pilots, “You and your crews will

probably be killed anyways.” (baseball-fever.com) |

Mike and the Pequot crew listened to the unusual 1944 World Series on the radio where the St Louis Browns and St Louis Cardinals played each other for the world championship at Sportsman Park - a stadium they shared during the regular season. (Saint Louis Browns Digital Museum)

|

We ate family style and the food was prepared by the mess cooks. We sat on long benches with folding metal legs. The clean-up crew would fold the legs up and put the benches on top of the tables so they could swab the floors after chow time.” He said the main crew sleeping quarters were in the forward part of the ship, in the fo'castle. “The forward deck hatch worked side-to-side like a door that’s how we’d get down there. It had bunks four high with four rows on one side and four on the other. This area slept 32 men. The best spot was all the way forward on the top bunk. It was all by seniority. Before I was discharged I finally got that bunk.”

|

|

|

Mike and his shipmates would listen to the radio in the Pequot’s mess hall. Here we see Frank Sinatra clowning around to entertain the troops during an Armed Forces Radio Service broadcast and announcer Jack Brown with Hollywood stars Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. (AFRTS photo) |

|

“The Captain's quarters had it’s own head. The crew’s head was located away from our sleeping quarters and we had to go outside to get the to head," Mike remembers. The “Black Gang” the engine room crew, had their own sleeping quarters in the aft part of the ship. “They kept to themselves, Mike remembers. “We’d meet on shore when we were on Liberty and got to know a few of them really well. They had to load all the coal themselves when we’d make port, but everybody had to pitch in when we were loading cable, even the cooks and the bakers. They had to help with cable and loading ammo.” Mike couldn’t remember if the large spools of cable arrived in port from a barge or by railroad but he said they had to load cable manually. “It was really heavy and we’d coil it aboard. It was all basically done by hand. We’d use a winch to get it up to the fo’castle deck then we’d go by hand to load it down into the cable hold.”

When the Pequot was laying or retrieving cable Mike’s duty station was up on the fo’castle deck. “I was up front with the winch equipment when we were playing cable out and I remember running all sorts of cable out to lighthouses and light ships, Mike explained.

|

|

|

Mike at his duty station with the large forward cable winch and the Pequot crew stowing cable by hand in the forward hold. (Mike Luongo Family) |

|

“When we had to

retrieve a broken cable end from the seafloor we used a big

grappling hook and the Captain would drag for it. Sometimes we

laid one end of the cable onto a buoy. Later the electricians

would splice it and toss it overboard. There where two main

electricians who did that work, Sullivan and O’Keefe. They were

both Irishmen from Boston who had worked for the power company,”

Mike tells us.

Mike’s assigned battle station was on the gun crew of one of the 20mm Oerlikons. “The gun locker was down below decks for small arms. But when general quarters sounded we never knew if it was for real or if it was a drill. We never did any live fire training with the 20mms but we were ready for combat all the time. A couple of times we spotted mines out in the ocean.” Mike adds. “Our escorts were mostly 83 footers with ash can depth charges on them. We seldom went out alone. We never had abandon ship drills but sometimes we would use one of the lifeboats to get ashore for liberty.” Mike tells us that every day at 1 pm they would have some kind of drill. “When we were in port we’d march, and if somebody screwed up the deck officer would embarrass us by making us march for punishment right there on Constitution Wharf in Boston. We were surrounded by Navy guys and they’d make fun of us and call us the “Hooligan Navy.”

|

|

|

| Boston's historic Constitution Wharf was the Pequot's home berth. Sailors Livingston, Luongo & Cidoni against a warehouse wall. | Time ashore on a winter's day. Mike Luongo (bottom) and two Pequot pals. | Mike Luongo on top of Paul Quinn who is on top of Bob Livingston |

“Out at sea we were assigned four-hour watches when we were on duty. We did all sorts of things like chipping paint and re-painting. We were doing that all the time, and every day the general seaman would wash the Pequot down,” Mike explained. “If it was very foggy we could pull lookout duty and have to stand watch up at the bow.” Mike said that sometimes the sea ice would get really bad on the Pequot’s deck and superstructure and they’d have to chip it off by hand.

|

|

|

Heavy ice from cold sea spray in Northern waters can build up to the point where a ship can capsize and sink. The Pequot’s mission often took her into that frigid danger zone. When ice would build up Mike and his crewmates would chip it off by hand and use a steam hose to break it free. Here behind her executive officer we see Pequot escort Subchaser 1296 covered in sea spray ice. (courtesy Marilyn Chapoton / map from NOAA) |

|

“Once up around Nova Scotia we had to break off a lot of ice and we even had a Coast Guard Ice Breaker ahead of us clearing a path for the Pequot,” Mike said. “It seems like in the winter we were up North freezing and in the summer down South where it was hot, but I do remember we’d anchor in warm water during the summer and have swimming parties. Guys would dive into the ocean off the mast and somebody would be in the dory as our lifeguard.”

LIFE ASHORE

When in port and on shore leave the Pequot crew had their favorite taverns around the Boston yards where they would get together, socialize, and let off some steam. "We had port liberty on alternate days they called Starboard Liberty. So you were on one or the other. I think the cooks had liberty anytime they wanted and on St. Patrick’s Day we all got special Liberty,” Mike remembers. “The very first night I went on liberty in Boston we all got in a bunch of trouble. They had a law there, which I’d never heard of, that said you couldn’t move drinks from one table to another,” Mike recalls with a laugh. “Well a bunch of us did that so they called the Shore Patrol on us. They picked us all up and hauled us all back to the Pequot in some big grey trucks that had seats in the back and a canvas top.”

|

|

In addition to the Pequot team that Mike and his shipmates played on, The Boston USCG District had an official basketball team that played throughout the region. (Patrol Magazine, January 1944, Catherine Calamaio WWII Scrapbook) |

Mike remembered some shore station recreation also, “We had a basketball team - The Pequot Basketball Team. Our uniforms were red jerseys and they had “USCG Training Station” on the front of them. We would play against teams from other ships that were in port. Bob Livingston was our big shooter. We called him “The Big Gun.” Our Chaplin and other crew would hold non-denominational church services, Mike tells us. “Even the Jewish guys would come and we’d all sing hymns.”

OTHER DUTIES AS ASSIGNED

Over time Mike worked his way off the deck and started doing some of the ship’s typing. Among his other duties he took over as Pequot postmaster and was in charge of the ship’s mail after Yeoman Norm Zinner left in 1946. ”We had mail call everyday when we were in port,” Mike explains, “The Pequot had a “fleet post office number” so when we were at sea they’d send the mail ahead of us so it would be waiting for us no matter where we put in and docked. We’d tease the new guys about having to find the next “Mail Buoy,” Mike chuckled. “Or we‘d tell them to go get a “pail of steam! Near the end of the war I also would get “helm watch” where as a Seaman I’d be on the ship’s wheel and would work with one of the quartermasters and the deck officer to mark-up the charts.”

Mike said a lot of sailors steered clear of Captain Sande, “He was one tough old Norwegian and nobody got in his way. I think some of the guys were afraid of him,” Mike recalls. “But he did alright by me. In 1944 we were out at sea and the word came in over the radio that my mother had suddenly passed away from a stroke at age 44. They called me up to the officer’s quarters about ten o’clock that night and gave me the word. Sande had a jeep waiting for me when we made port in Boston and all of the paperwork was already made out for 10-days of emergency shore leave. I just made the end of my Mom’s wake.” I really appreciate him doing that for me,” Mike adds.

Among the highlights of his Pequot service Mike vividly remembers when the Pequot escorted the captured German weather ship Exernsteine into Boston harbor. See Quartermaster Lou Carhart’s story for details on that colorful chapter in Coast Guard history.

WAR'S END

Mike stayed with the Pequot

until well after Japan had surrendered. “On V-J day I rode

around on a fire engine. It was just an unbelievable party all

night long and you could get drinks for nothing. That was really

something else,” Mike recalls. “But once the war ended they

froze the ratings. That was OK since I had a good job but even

though I had enough points I was classified as “essential.”. If

you were stationed on land you would get 1 point but since I had

sea duty I got 2 points. But it didn’t matter. I was already

engaged to be married and was ready to get out. But since I was

classified as “essential” I had to stay in the service for

another 6 months. I wasn’t real happy about that at all,” Mike

adds.

|

|

| In this newspaper clipping we see that Pequot's Mike Luongo was an award winning bowler at the Fleet Club. | Luongo and Hoganson in their dress white uniforms. |

By this time the Pequot was starting to show her age and in addition to removing barnacles and general maintenance there were problems in the engine room so she spent time in port in Staten Island for repairs and later at the Charleston Navy Yard in Boston across the bay from the Coast Guard Station.

Mike was finally discharged in March 1946 from the Brooklyn Navy Yard while Pequot was in dry-dock. Shortly after getting out of the service he married Angelina "Lee" Gengaro on May 5, 1946. After the war he worked as a supervisor for a number of companies, including many years with a firm that manufactured disposable vacuum cleaner bags.

“There was a Pequot crew reunion of sorts in Chicago about 5 years after the war and I learned that some of the guys stayed on and made a Coast Guard career out of it, but after that I never heard anything else. Hoganson stopped once by to see us after the war with his wife and two kids. He went into the Naval Reserve and then they called him back into the Korean War until he was discharged out of Florida,” Mike recalled.

|

|

Mike at 89 enjoying the peace and tranquillity of the Atlantic Coast that he helped to protect as a young Seaman. Oak Island, North Carolina 2011. (Luongo Family Photo) |

In addition to supporting his family, Mike always found time to play cards with his friends, he stayed active in several bowling leagues, and just loved to play golf. He fully retired in 1985. Mike and Lee raised three sons and have five grandchildren and one great grandchild.

Seaman Mike Luongo currently

resides in Toms River, New Jersey.

Every effort has been made to trace and acknowledge copyright. The authors would welcome any information from people who believe their photos have been used without due credit. Some photos have been retouched to remove imperfections but otherwise they are true to the original.

FEEDBACK

If you have comments or queries specifically

about the Pequot or her escort ships, please contact

Chip Calamaio

chipaz@cox.net, Phoenix, Arizona,

USA. (H) 602-279-4505.

Click here to go to the Pequot Main Page.