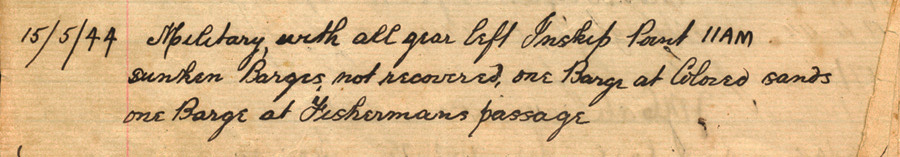

INSKIP POINT

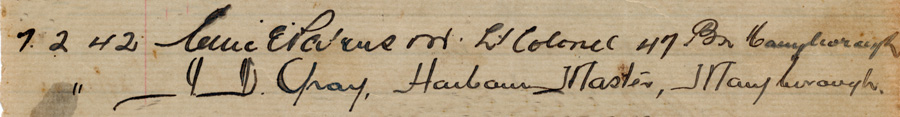

LIGHT AND SIGNAL STATION

|

|

|

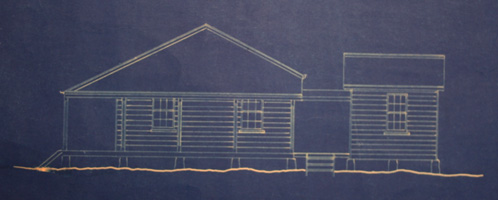

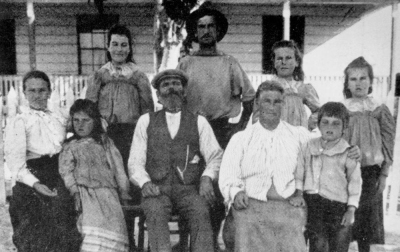

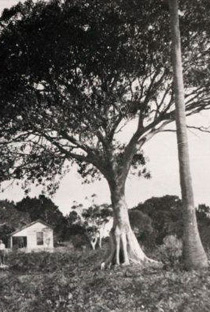

| Pilot's Cottage 1902 | Unloading at Inskip 1902 |

Former cottage site - Inskip 2009 |

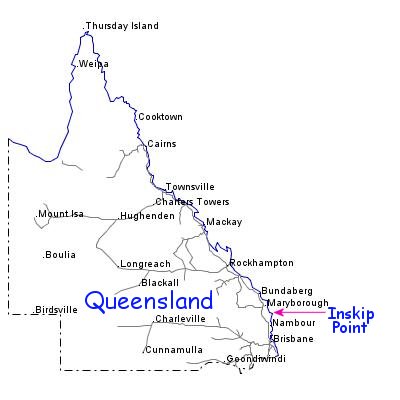

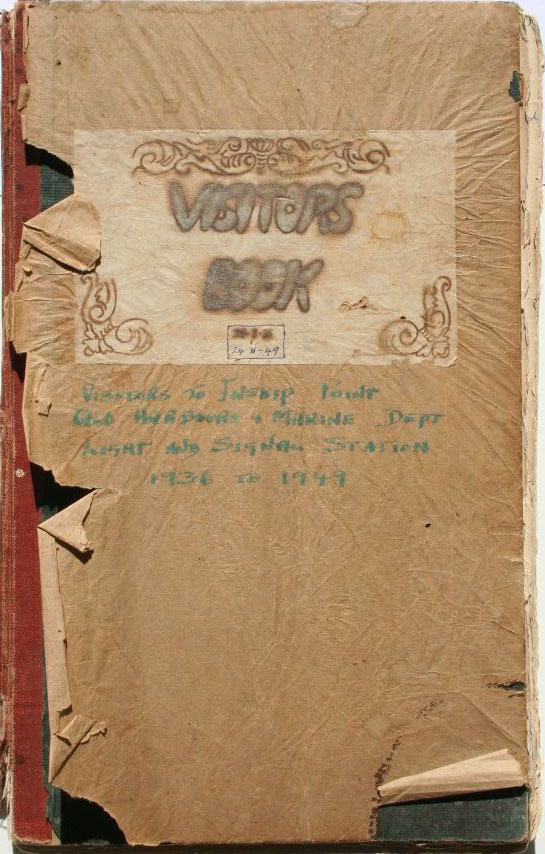

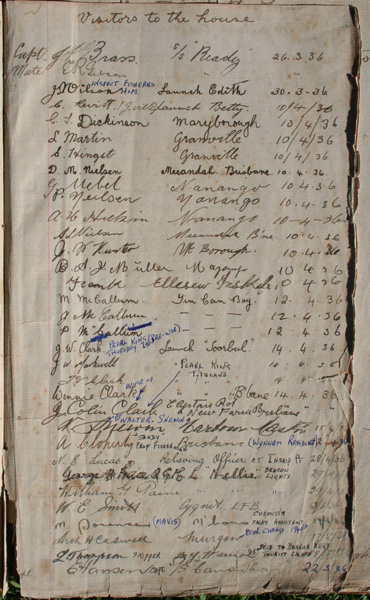

This is the story of the light and signal station at Inskip Point - just next to K'gari (Fraser Island), Queensland, Australia. The station began as the location for a beacon for the port of Maryborough in the 1860s, to a pilot station in the late 1800s and a light and signal station in the early 1900s. For more than a century the light station and pilots at Inskip were responsible for the safety of ships at sea. It was a lonely way of life for a succession of men, often with families, as they responded to the call of people in need.

|

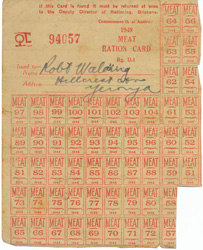

If your family was there or if you have any feedback please email me: waldingr49@gmail.com Dr Richard Walding |

|

|

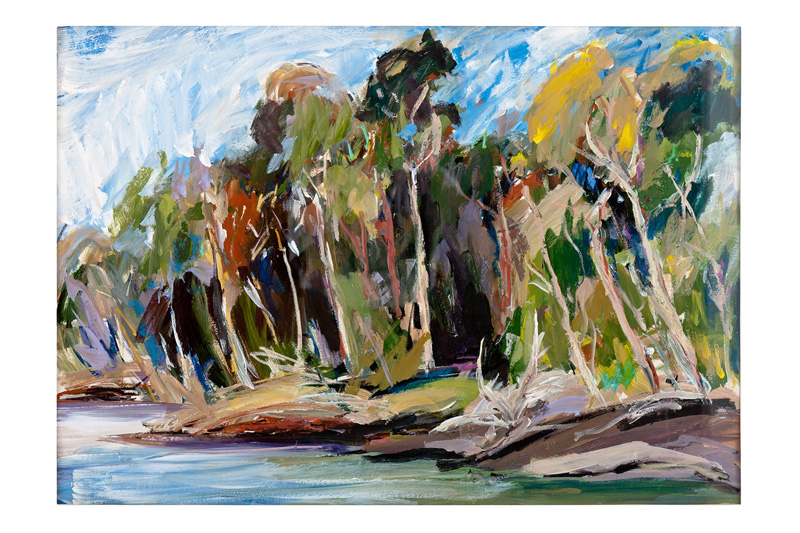

The main beach at Inskip Point where stores would be unloaded for the light station - once located 70 m inland to the left. On the right is Snout Point - so named because it looks like the snout of a dolphin. It is the landward side of the southern tip of Fraser Island. In the distance is the Great Sandy Strait and the Port of Maryborough. "Bar-bound" ships would anchor in the deep channel just beyond the tip of Inskip Point. (R. Walding, 2009) |

LINKS TO SOME OF MY RELATED PAGES:

Comboyuro Point and Cape Moreton Light Stations

Moreton Bay Harbour Defences - World War 2 (Bribie Island, Fort Bribie, Moreton Island)

Inskip Point - Latitude: 25° 48' S, Longitude: 153° 04' E.

ORIGINS OF THE NAME

Inskip Point was named by Captain Owen Stanley, the Admiralty Hydrographer and Commander of the HMS Rattlesnake in October 1849 after Captain George Henry Inskip RN naval officer who served in HMS Rattlesnake and HMS Bramble October 1846 to 1849. Captain George Henry Inskip, born in Plymouth around 1824, was son of Peter Inskip and Harriet Palmer. His father was a sailor and his brother was Captain Peter Inskip (b 1808). It seems George was quite prolific in naming remote coastlines and spent some time in the 1850s in British Columbia. The 1881 census lists him as Head of the house (click to view census document).

|

.jpg) |

| The HMS Rattlesnake depicted near the reefs of the Louisiades to the north of Australia on 14 June 1849. While the Rattlesnake hauled off and waited, Lieutenant Yule of the tender Bramble (to the left) examined the opening in one of his boats. State Library of NSW. | HMS Rattlesnake, painted by Sir Oswald Walters Brierly, 1853. National Maritime Museum, London. |

The voyages of HMS Rattlesnake and tender HMS Bramble along the Queensland coast were really rather famous. From 1846 to 1850 the Rattlesnake, an ageing 'donkey frigate' (28 guns) tendered by the schooner HMS Bramble, carried on from the earlier surveying work of HMS Beagle (Darwin's ship)1. On 16th October 1847 Rattlesnake visited Moreton Bay en route from Sydney anchoring at Cowan Cowan Roads in Moreton Bay. She departed 4 November. In this time Scottish-born naturalist John Macgillivray (1822-1867) visited Moreton Island and studied aboriginal languages (this was the first encounter of the Rattlesnake with aborigines) and collected flora and fauna.

In a second visit, HMS Rattlesnake under the command of Captain Owen Stanley, and HMS Bramble (under command of Lt Charles B. Yule and 2nd Master George Henry Inskip) entered Moreton Bay on 17 May 1849 on their way from Sydney to Cape Deliverance passing Fraser Island and the Great Sandy Straits. Rattlesnake and Bramble surveyed much of the northern East Coast of Australia - (treacherous because of the massive string uncharted reefs & shoals of the Great Barrier Reef ) and later Torres Strait & southern New Guinea.2

Macgillivray's journal is available online.

WHY INSKIP POINT?

Brisbane had been established as a penal settlement as a part of New South Wales in 1824 after surveys by John Oxley in late 1823. The first navigation aids to assist vessels entering Moreton Bay were those placed by John Gray in 1825 to mark the outer bar and inner channels for vessels entering by the South Passage. It was about this time that Fraser Island, and to some extent the point now known as Inskip, assumed world notoriety due to the Eliza Fraser story.

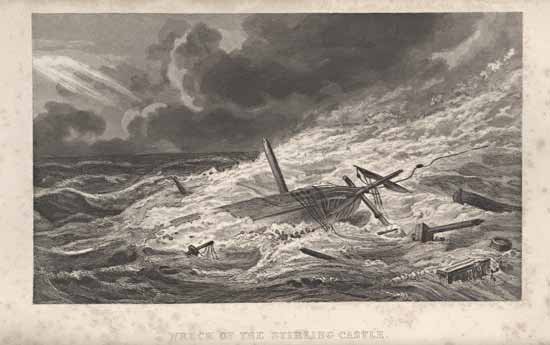

In 1836 the Stirling Castle was wrecked on the Queensland Coast and two boatloads of survivors headed south to Moreton Bay. One boat bypassed Moreton Bay and arrived on the northern New South Wales coast - with one survivor. The other boat containing Captain Fraser, his pregnant wife Eliza and 10 other men made it to Orchid Beach on Fraser Island, 20 miles south of Sandy Cape. There they were watched-over by local aborigines - the Dulingbara clan. Because she was still bleeding after giving birth (to a baby that only survived a few hours), Eliza Fraser was confined to living with the aboriginal women at Hook Point on the southern end of the island (see map above). She was taken over to Inskip Point in canoe and thence to Rainbow Beach and rescue at Lake Cootharabah.

Five men sailed separately to Inskip Point and three walked to Bribie Island to be rescued to Lt Otter and two men walked to Lake Cootharaba. Another two men, Elliott and Doyle, tried to swim from Hook Point to Inskip Point but drowned during their attempt. Fraser Island had become world famous - more for the increasingly elaborate and dramatic stories by participants and witnesses than for the natural beauty and resources of the island.

|

The Wreck of the Stirling Castle - 1836 |

In the following years exploration and closer examination of Queensland's coast proceeded. For example, in 1842 Andrew Petrie discovered and explored what is now the Mary River and considered the land nearby suitable for grazing sheep. In 1847 the first shipment of wool from the Wide Bay district was taken to Sydney by the Schooner Sisters. By June 1848 wharves had been built on the north side of the river and the port became known as Port of Wide Bay - later Port of Maryborough. With the start of free settlement in 1842 the number of ships heading for Queensland increased dramatically. At the time of Queensland's separation from New South Wales in 1859 ports had already developed where there was access to the hinterland and safe anchorage for ships: Moreton Bay, Wide bay (Maryborough and Bundaberg), Port Curtis (Gladstone) and Fitzroy River (Rockhampton).

The Wide Bay district continued to grow and in 1848 the first Harbor Master for Wide Bay was appointed: Government Botanist John Carne Bidwell. Not only did he perform harbour duties but he was also Commissioner of Crown Lands, Registrar of Births, Marriages and Deaths and had to perform marriage ceremonies and act as a magistrate. He died in 1853 aged 38 after being lost for 8 days in the bush at the head of the Mary River. He had forgotten to take his compass. The Government of NSW, located in Sydney, was not over-generous to the northern ports, especially as separation approached. Nevertheless, in 1857 £1000 was voted for improving navigation (mostly for wool ships) in the Mary River.

In 1859, the Sub-Collector of Customs for Wide Bay Richard Sheridan was appointed Harbor Master and, although not a nautical man, remained at this post for 19 years. He worked single-handed at first from a little office which later became the kitchen for the Criterion Hotel in Wharf Street, Maryborough. Not only was he the Harbor Master but also Water Police Magistrate, Emigration Agent and later, Polynesian Inspector for the kanaka labourers. The first pilot he employed was Joseph Mungomery from Sydney. Note spelling of harbour when referring to the place, as distinct from the title Harbor Master. This has changed in the official Queensland literature over the years.

On a personal note: I sailed around the southern end of the Great Sandy Straits in October 2009 and the recent maps of sandbanks and channels had to be read with caution. Many of the sandbars had moved and channels were not where they were expected. We revisited the spots mentioned by Jack N. Devoy in his travel narrative of the Great Sandy Straits "A Yachting Cruise".3 This revisitation is described later.

|

|

Solar powered beacon with Fraser Island to the right. |

We passed over this sandbank two hours earlier. |

The harbour pilot and two boatmen were stationed at Maryborough, several kilometers up the Mary River. Masters of vessels frequently had to leave their vessels at anchor in the bay and go up in their boats to secure the Pilot's services. The discovery of gold increased the trade at this port but an increase in pilot staff did not come at the same time. There was just the pilot and the coxswain of the pilot vessel. When the coxswain was engaged as the pilot, there was insufficient crew left behind to man the pilot vessel. A situation that was clearly going to get unmanageable.

WHY IS THE WIDE BAY BAR SO DANGEROUS?

The Wide Bay Bar - like all bars - is a shallow area of sand deposited near the mouth of a bay or river. When the water from the Sandy Strait slows down to meet the ocean, it deposits tons of silt and mud that it carries. That's the Wide Bay Bar - which extends across the southern entrance near Inskip Point. The seas along the bar are usually much larger and steeper than the ocean swell or the wind waves outside the bar (and certainly larger than the calmer waters in the Strait). Add together a powerful current coming down the Strait, large areas of dangerously shallow water between Inskip and Fraser, and tricky navigation with channels that shift frequently, and you have a recipe for disaster, even for large vessels.

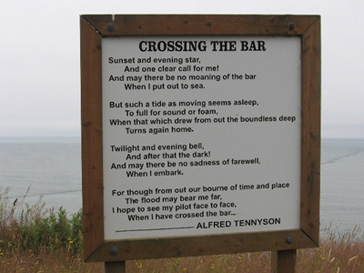

The benefit of having a lightkeeper at Inskip (and Hook Point) is that they can signal the state of the bar so captains can get their timing right. Flags were flown from posts at Inskip Point and Hook Point: a "four seas" pennant meant that four "seas" or breakers were visible on the bar and that coastal vessel should not cross. Later, signal arms were used (as limp wet pennant flags are not easy to decipher). It was considered advisable not to cross if more than three-seas were running. Wide Bay Bar conditions are strongly influenced by tides.

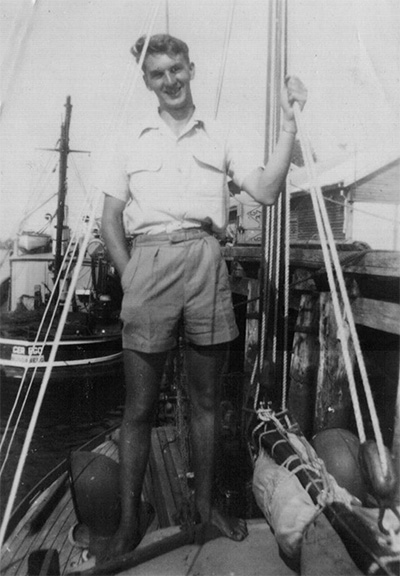

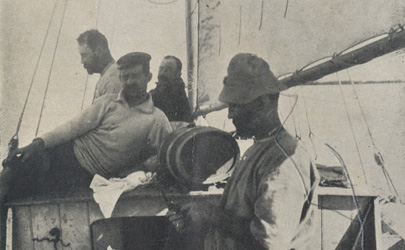

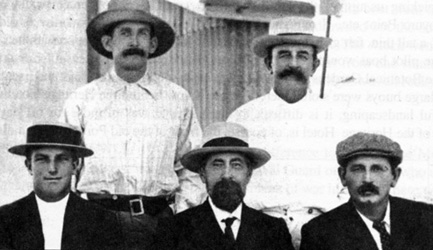

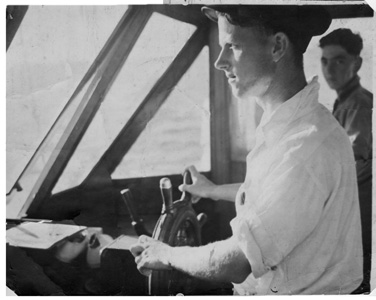

Barry Mulligan was a Cadet Surveyor with the Harbours and Marine Dept in the early 1950s. The photo abovewas taken aboard the QG MV Ferret moored at Hyne & Sons wharf at Maryborough. While the photo is not dated, it was taken at the time they were doing the Wide Bay Bar survey. The vessel in the back ground is the Cerego which ran weekly services between Brisbane and Maryborough via Wide Bay Bar. The Ferret and crew were involved in a complete survey of the whole Hervey Bay /Wide Bay area including Urangan and approaches, as well as a bank to bank survey of the Burnett River from the Town Reach to Burnett Heads. This was related to the introduction of bulk sugar terminals. |

Sometimes the current is so strong that smaller or slower vessels simply can't make headway against it, and it can quickly sweep a vessel into dangerously shallow water and breaking surf. Often, these dangerous conditions will subside dramatically when the tide turns. Many accidents on bars are the direct result of mariners either being unaware of the tides or choosing to cross at the wrong time. The lightkeepers of Inskip Point have saved countless lives in the 100 years they were there.

THE ROLE OF THE PILOT, COXSWAIN & BOATMAN

|

An ocean-going steamer takes a pilot aboard from the smaller pilot steamer while the boatman rows the coxswain back to the Pilot Station. This was sketched by J. R. Ashton in about 1885 from first-hand experience while he lived Queensland. The ships and location are unknown but, given the date and the route of Ashton's perambulations, it could be the pilot steamer Llewellyn lying off Bulwer in Moreton Bay. Source: Picturesque Atlas of Australia (1887). |

It is worth describing the various titles and functions of the pilot staff at Maryborough, and in fact this will apply to Inskip Point as well. The coxswain is the master of the pilot boat (owned by the Department of Ports and Harbours). He will take the pilot from shore station out to the steamer or other ship requiring safe passage through the straits. He steers the boat. The coxswain will have one or more deckhands to operate the sails or row the pilot boat. These deckhands are skilled operators of boats and are called boatmen.

Once the pilot has boarded the ship (often by Jacob's Ladder) he will advise the ship's master of the course to sail. The pilot provides advice (only) to guide the ship through dangerous or congested waters. He will have knowledge of the tides, swells, currents, sandbanks and shoals that may not be on nautical charts. He has local knowledge. He is not in charge as the master remains in charge (legally). The pilot may give instructions such as "10 degrees to port" to the seaman on the helm who carries out his instructions with the agreement of the master.

You may ask if the Pilot would ever row the pilot boat himself. An experience coxswain - Kevin Mohr - said "not bloody likely". In other situations such as at Bulwer, off Moreton Island, the Pilots would live aboard the Pilot vessel (such as the steamer Llewellyn) and the Pilot vessel would lie at anchor awaiting signals from the lighthouse (in the case of Bulwer Pilot Station, that was Cape Moreton Lighthouse).

When a coastal ship was spotted by the Lightkeeper at Cape Moreton, typically at 8 miles distant he would fly a particular pennant and the Pilot vessel at Bulwer - some 7 miles (11 km) away - would take note. When the ship was closer, perhaps 4 miles, the pennant would be changed and the Pilot would await a "want a pilot" signal. Pilots would be rowed ashore only when their period of duty was up - be it days or weeks.

THE PILOTS AND LIGHTKEEPERS OF INSKIP POINT

At its inception in 1859, the new colony of Queensland adopted the laws of its parent - New South Wales. Responsibility for ports was given to the Harbor Master in Brisbane (W. H. Geary) - under the control of the Customs Department - which in turn was under the control of the Colonial Treasurer.

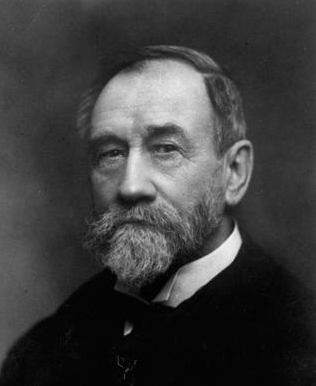

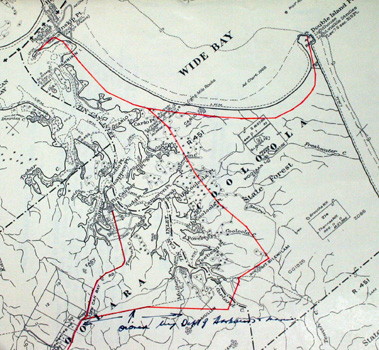

In September 1860 Lt George Poynter Heath RN was appointed Marine Surveyor in the Department of the Surveyor General. One of his first tasks was investigate a new harbour to the north of Brisbane which would provide shelter for vessels hindered by bad weather from crossing the Wide Bay Bar at Inskip Point, and also be suitable for vessels to load the timber which grew in Tin Can Bay and Fraser Island. Aboard the Spitfire, Heath departed Brisbane on 15 April 1861 and reported back to the Board which was delighted with his work.

In 1862 Heath was appointed to newly created position of Port Master to take overall charge of the Harbour Master's Department and and in 1863 a new Marine Board was constituted and given responsibility for the renamed Department of Ports and Harbours. Maryborough was one of eight ports to be recognised and had its own Harbour Master (Richard Sheridan), Pilot (Henry Croaker), an Acting Pilot (Joseph Montgomery) and two boatmen. Maryborough was booming; wool had already become an export commodity by 1860 and the only town in Queensland returning a trade surplus was Maryborough.

In 1866 the wage for the men at Maryborough was a total of £67-12-6 per month with the Lightkeeper at Woody Island (in the Great Sandy Strait) receiving a further £12-5-0 per month. The area seemed destined for new facilities but history proved otherwise. Prior to separation there had been only four ports in the colony: Moreton Bay (Brisbane), Wide Bay (Maryborough), Port Curtis (Gladstone) and Fitzroy River (Rockhampton). More ports were slowly being added to the list as Queensland developed and by 1863 there were another four: Curtis Island, Broadsound, Pioneer River and Port Denison. However, most of the ports were river ports which suffered from flooding, silting-up and difficult navigation. They were also developing somewhat haphazardly.

The government set up an inquiry into the state of harbours and rivers in the colony and in 1864 it made several recommendations for improvements - none of which included the southern (Wide Bay) entrance to Maryborough. This was disappointing for exporters using the Maryborough port. The Sailing Directions for the port made it obvious how inaccessible it was. They warned "do not proceed to sea if there is any break across the [Wide Bay] bar, as it is attended with great risk and danger from the short abrupt sea which comes in, in the shape of rollers, with great velocity." From the Wide Bay Bar at the southern end there was a buoyed and beaconed channel to the mouth of the Mary River passing over shallow flats having no more than 5 foot (1.5 m) of water over it.

Strangers to the area were advised to ask the natives of Fraser Island to come aboard and offer assistance guiding the ship through the narrow shallow channel. It was about this time - 1862 in fact - that the first emigrant ship to come directly to Maryborough from England arrived. The Ariadne left Liverpool on 5th June 1862 and arrived at Maryborough on 9th October with 260 people aboard. By the time direct migration to Maryborough stopped in 1890, 21000 emigrants had arrived at the port.

|

Lt. George Poynter Heath RN. Marine Surveyor and First Portmaster of Queensland, 1862- 1890. JOL. |

The discovery of gold at Gympie by James Nash in 1867 was reported in Maryborough on October 16, 1867. Within a week Maryborough was deserted, the sawmills were idle and crews deserted ships in their rush for gold. However, the opening of the goldfields at Gympie lead to a great increase in the demand for services at the nearest seaport of Maryborough but there was one big problem. The small staff could not cope with the demand and many ships went unpiloted.

Some of the problems can be attributed to the loss of men as they headed to Gympie seeking their fortune; but there was a second problem, namely the organisation of the services. A large part of the pilotage work was done by men employed in the Customs Service and because the [Mary] River Pilot was often doing the duties of the Sea Pilot he and his boat not often at Maryborough.

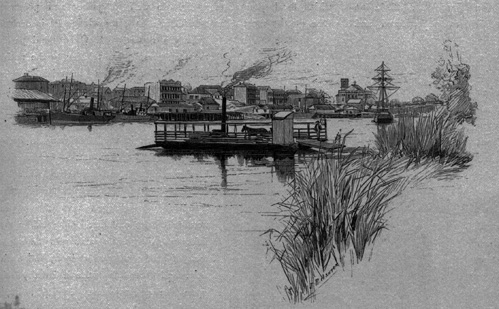

|

The Port of Maryborough in 1887 - as sketched by Julian Rossi Ashton (b 27 Jan 1851) while living in Queensland for the Picturesque Atlas of Australia (1887). These volumes were given to me from the James Campbell & Son (sawmillers) estate. |

Harbor Master Sheridan (also Collector of Customs) was not a nautical man but tried to maintain an efficient service. However, he had insufficient time to develop sound systems in the port. For example, for three months in 1868, the markers for crossing the Wide Bay Bar were not distinguishable from outside the bar in bad weather - a decidedly inferior situation. As well, about 40 miles north of Inskip Point was without channel markers. This may have been a small problem to boats of shallow draught that had experienced masters who travelled the channels constantly, but to vessels of increased draught there caused great concern. In fact, they would have to get some unqualified person to help or go the extra 160 miles around the Breaksea Spit at the northern tip of Fraser Island. In the first nine months of 1868, 49 vessels had crossed the Wide Bay Bar at Inskip Point all without the services of a pilot. Portmaster Heath in Brisbane was alarmed at the possibility of losing a ship on the Bar - with all souls - that he proposed a telegraph service be operated by lightkeepers at Inskip Point; but to no avail - not straight away. During 1868 ninety-three vessels required piloting to and from Maryborough compared with eight the previous year (not including those boats for which there was no pilot).

|

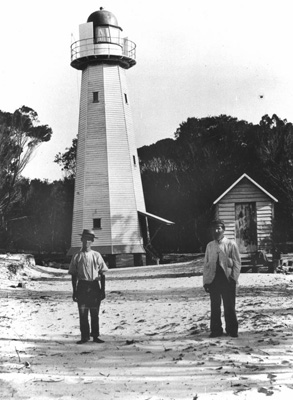

Inskip Point in the early days. Date and photographer unknown. |

The revival of the economy in the early 1870s saw renewed interest in attending to the Wide Bar Bar. A decision was made to build a light-keepers' cottage for a Pilot at Inskip and tenders were called on August 30th 1872, to be in by 27 September. A pilot station was set up at Inskip Point in 1872 to help guide ships through the Wide Bay Bar and up the Great Sandy Strait to the Port of Maryborough.

The first pilot was John Smith, coxswain of the pilot schooner at Port Curtis (Port of Gladstone) - appointed 1 September 1872 on a salary of £96 pa - assisted by coxswain and two boatmen according to the Government Gazette (28 December 1872). Two lightkeepers were also appointed - John Carbery (b 1857) and John Watson (b 12 July 1823). Pilot John Smith was born in Lubeck Germany (70 km NE of Hamburg) in 1836 and migrated to Australia probably in 1861 (to Moreton Bay under the name Schmidt - we can't be sure) and made his way to Gladstone. There he took an appointment as coxswain of the pilot schooner at Point Curtis on 4th August 1871. He married an Irish woman Anne Cullamy - aged 27 - in Brisbane in 1872 and had returned to Point Curtis to resume work before being appointed to Inskip Point.

An additional appointment was made in 1873 - that of Head Lightkeeper - George Byrne. That was the year of a big gale that caused severe landslips at Inskip Point and, as timber merchant William Pettigrew noted in his diary, the Pilot's house being built and all their belongings - boats, boat-shed, tents and provisions - had been washed away (Friday 19th January 1873) [BC 22 Jan 1873].

|

The barges for Fraser Island now leave from the edge of the sand. One day this will all slip away quite unexpectedly - and then return. Looking East. |

By early 1875 a telegraph line had been installed from Maryborough to Inskip and the job of Post and Telegraph Office Keeper was given to the Lightkeeper George Byrne. As lightkeeper he was awarded a wage of £96 pa plus £40 pa to act as Postmaster and Electrical Telegraphist, another £40 pa as a "Foraging Allowance" and for the purposes of budgeting, the value of the Lightkeeper's Quarters was £26 and a further £10 was allocated for Long Service Allowance. Byrne continued in this role until 16th April 1886 when he was transferred to Double Island Point and Daniel Gorman took over. In 1877 Pilot John Smith and his wife Anne had their first child - a daughter Mary Anne born on 4th September at Inskip Point.

THE REILLY FAMILY: INSKIP POINT 1875 -1902

|

Depiction of a seaman migrating to Maryborough in 1887 - as sketched by Julian Rossi Ashton for the Picturesque Atlas of Australia, p366. I imagine that seaman Samuel Reilly would have dressed like this. |

My great grandfather was Samuel James Reilly (pictured below) who joined the Queensland Lighthouse Service (Marine Department of the Queensland Treasury) as the Pilot & Receiving Officer at Inskip Point on 1st December 1875. He arrived at Inskip with his wife Emily and 5 month old daughter Emily Jane, born in Maryborough. His real name was Samuel Crouch - born in Middlesex, England, on 21 February 1839 - son of Stephen Crouch and Mary Ann Crouch (nee Reeves) and became an Able Seaman by age 19. He had a brother and four sisters.

The 1851 and 1861 census documents from England make this clear. He was a seaman who arrived in Sydney in February 1864 aboard the Castle Howard from England under the assumed name Samuel Riley. Instead of continuing his contract he "jumped ship" in June 1864 and deserted instead of sailing to Shanghai and back to London aboard the Castle Howard. He was charged with desertion, convicted and spent 14 days in gaol. Riley worked as a seaman on ships between Sydney and China before settling settling in Queensland in about 1869 under the name Reilly. He worked as a mariner on coastal ships between Sydney and Cooktown. In April 1875 at Maryborough he married Emily Compton - from Middlesex England - who had arrived in Maryborough aboard the Glamorganshire 3 May 1874 (aged 20), accompanied by her sister Amelia (26) - also from Middlesex England.

|

|

Emily and Samuel Reilly - 1906 |

Samuel Reilly - 1906 - in the heathland swamp behind the Comboyuro Lighthouse on Moreton Island; an area once known as "The Shallows" or Clifton Waters. Source JOL 170525 |

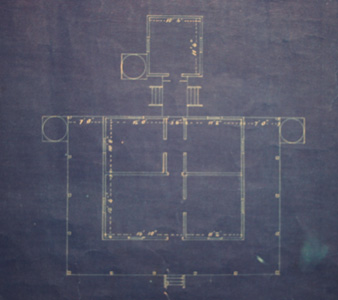

In June 1875 their first child, Emily Jane, was born and then the following year, May 1876, their second child Amelia Beatrice Reilly was born at Inskip Point but she died the following year and was buried at Maryborough Cemetery. On 27th April 1877 tenders were called for the erection of Pilots' cottages at Inskip Point. The tenders closed on May 18 that year but the successful tenderer Messrs Helmes & Co. were not appointed until 4th March the following year (1878). They began on the first cottage almost immediately and by November they had erected four more there. In the Government Gazette of 26th January 1878 tenders were invited for the construction of a Lightkeepers Cottage at Inskip.

On the 16th March (The Queenslander) it was announced that Messrs Helmes & Co. were again the successful tenderer. There were now five houses, including George Byrnes' cottage, and the attached Post and Telegraph Office. In July that year the Reilly's first son - William Walter - was born (July 28) , followed by Samuel Stephen on 12th September the following year (1878). The cost to masters requiring pilot services was set in 1878 at 1 pence per ton (foreign), ha'penny per ton (intercolonial) and a farthing (¼ penny) per ton for coasters.

|

Looking towards the mainland from the passage side of Inskip Point. To the right is Pelican Banks and beyond that is the Great Sandy Strait. To the left is Pelican Bay and further on is Tin Can Bay. (R. Walding, 2009) |

In 1879 Maryborough Harbor Master Sheridan visited Inskip and recommended that extra lights be installed to assist the crossing of the Wide Bay Bar. On 10 January 1880 two white leading lights were installed at the western end of Inskip Point under the instruiction of Portmaster G. P. Heath. Soon after (3 February 1880) Samuel Reilly was promoted to Boatman Pilot "for the Port of Maryborough for vessels whose draught does not exceed 12 feet". As well that year (1880) the Reillys had another daughter - Maud - in Jan (11th) and a son Herbert Winterly in April the following year (3rd April 1881). The infant Herbert died 11 months later in March 1882, and he too was buried at Maryborough.

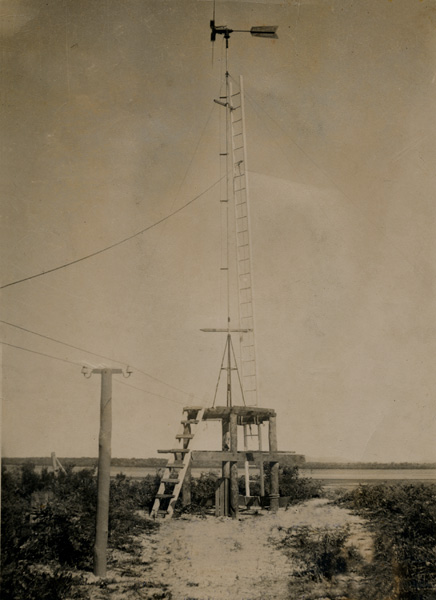

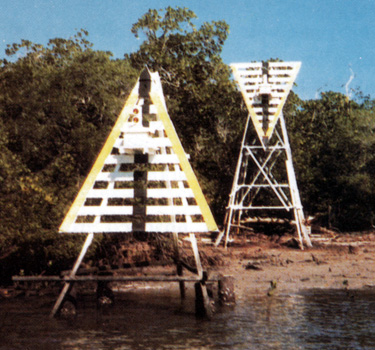

The year 1881 saw some dramatic improvements to the Wide Bay Bar. The Department erected large black leading beacons on the shore at Inskip Point. The use of black instead of the white previously used made them easily visible towards sunset when the light was behind them, although the old white beacons had the advantage when the sun was to the east. A cottage had also been built at Hook Point and he was responsible for lighting the leading lights for crossing the bar at night. Vessels could cross the bar at night from outside the bar providing the captain could judge, from the sea conditions and swell on the coast, as to whether the bar was safe to cross, but going out over the bar was far more difficult.

By 1881 three pairs of lights led a vessel not only over the bar but five miles up the Strait, and a further pair at the Quarantine Station led in between Mary Heads. Additional buoys had been placed near Snout Point and Southern White Cliffs both on Fraser Island where it was difficult to keep beacons in position because of the sandy bottom.

|

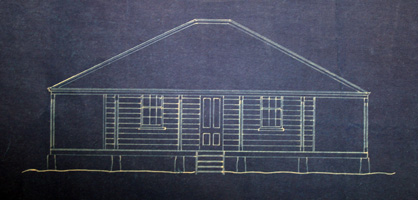

Plan of the Lightkeepers Cottages. They were about 24 ft wide by 21 ft deep and had verandahs 7 ft wide on three sides. The store was about 11' 6" square. You can also see the three 800 gallon water tanks. |

Staffing at Inskip remained unchanged until 1882, namely John Smith (Pilot), John Carbery and Watson (lightkeepers), Byrne (lightkeeper and telegraph officer), and Reilly (boatman pilot). Reilly applied for a Provisional School at Inskip Point to cater for the growing number of children. As well as his own four - Emily Jane (8), William Walter (6), Samuel Stephen (5) and Maud (3), there were a total of 11 school aged children. George Byrne and his wife Fanny (nee Williams) had George Thomas (8) and Reginald (6); John Smith and his wife Ann (nee Cullamy) had Mary Anne (6), Charles Anderson and his wife Elizabeth (nee Quinlan) had one - Charles (4), and Francis Peres and his wife Hilda (nee Strandquist) had two - Ellna Therese (5) and Hilda Elizabeth (4) - see below. Mr and Mrs Reilly also had twin babies - George and Blanche - four months old.

|

Jean Francois (Frank) Peres was born in the small village of Trèveneuc, Brittany, France, with a surname originally spelt 'Piresse'. He is shown here with his wife Hilda whom he married in Maryborough in 1877. Frank was a crew member aboard the 'Star Queen' that arrived in Maryborough in 1875. He deserted the disgustingly dirty 'starving ship' soon after. Frank was known to have had a sailing ship tatooed on his back which moved when he rippled his muscles. (Patricia Wiltshire) |

|

| The Peres family later in life: Celma (b 1885), Hilda (b1879), Amy (b1891), Ethel (b1893), Frank jnr (b1881), mother Hilda, Elsie (b1895), Agnes (b1897) and Theresa (b1878). Father Frank Peres (Snr) died in April 1916. (Patricia Wiltshire) |

My grandmother Ada May Reilly was yet to be born, as were also the other eight Reilly children. Up in Maryborough there was a changing of the guard: after 19 years as Harbor Master Richard Sheridan retired and Captain Edward James Boult was appointed in his place. In Sheridan's time three lighthouses had been erected (two at Woody Island and one at Sandy Cape), Hervey Bay had been charted and beaconed, and a Quarantine Station set up at White Cliff. On 12 July 1884 another landslip occurred at Inskip. It was about an acre in size. Smith, Carbery and Watson were awoken by a tent falling on them. Why they were in a tent is unknown. They had hardly any time to free themselves before they were surrounded by boiling surf and a constantly receding shoreline and soft sand.

Boatman John Frederick McGregor-SkinnerIn 1885 John Frederick McGregor-Skinner (Mariner) obtained work at the Inskip Point Pilot Station. Upon arrival in Townsville John McGregor-Skinner obtained work as a mariner at the Pilot Station on Ross Island at Townsville where the family set up home. This was the Pilot Station for Cape Cleveland. John and Mary's daughter Mary Eleanor died of TB four weeks later (on 6 December 1882). Five weeks later her twin sister Euphemia Elizabeth also succumbed to TB - no doubt caught aboard the ship. The girls were buried at the local cemetery. Just one week after Euphemia's death a son George Herbert was born at the Station (19 January 1883). John and his family left Ross Island in 1884 and headed south for Maryborough. It seems that John then obtained work with the Pilot Service for Wide Bay which operated out of Maryborough. The service included the Pilot Station at Inskip Point. It was here that John and his family took up residence in one of the station's cottages alongside the Lightkeeper George Byrne and Boatman Pilot Samuel James Reilly (my Great Grandfather). It seems that John was not an employee of the State Government as there is no mention of his appointment in the Government Gazette, either at Ross Island or Inskip Point. It is more likely he was a contractor carrying out mariner's duties.

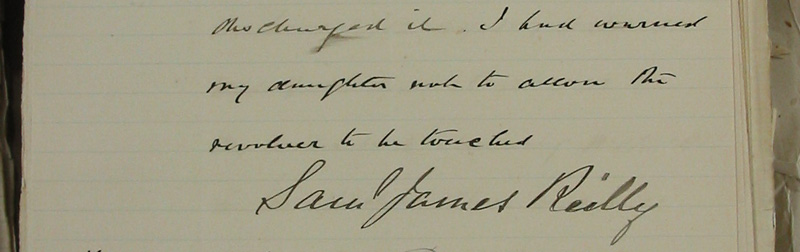

On 25 March 1885 John and Mary had a child - Robert Philip - at their cottage at Inskip Point. He was delivered by the Pilot's wife Mrs Emily Reilly (my Great Grandmother) who acted as nurse-midwife. At the age of 9 months on 7 January 1886 Robert died after a three-day battle with croup and was buried near the cottages at Inskip Point. Both Mr and Mrs Reilly were witnesses of Robert's death and their names appear on the death certificate. Click here to see a copy of the birth and death certificates. The other children - Fred (aged 9) and George (2) - were living there at the time. Fred attended school at the station. The family moved south again after their tragic start to life in Australia and arrived in Sydney in mid-1886. John deserted his wife Mary and married Elizabeth Reader with whom they had several children. He divorced Mary in 1893. John committed suicide at Botany Bay in 1905 with a gunshot wound to the head. My thanks to Donald Reid, great grandson of John Frederick McGregor-Skinner. |

In 1884 Francis Peres joined the team and Carbery and Watson were transferred. Captain Heath reported in November 1884 that a new cottage at Inskip Point had just been built and was just about ready for occupation. A most important change occurred on 1st February 1886 when George Byrne was transferred to the Double Island Point light. He was replaced by Daniel Gorman who was previously stationed at Sandy Cape on the northern end of Fraser Island. Daniel Edward Gorman (born County Cork, Ireland, 1838) and his wife Johanna (nee Hayes, b 1840) were married on 11th July 1864 at St Stephen's Cathedral in Brisbane and Daniel entered Government service immediately after. He was at Sandy Cape from 1873-76 and then at Gatecombe Head, Gladstone for three years followed by a few years Lady Elliott Island until 1882.

The Gormans moved back to Sandy Cape Light in 1882 to replace the 51-year-old John Simpson who had died of a gunshot wound. Simpson had been a lightkeeper for 26 years starting on 1 January 1856 as the principal lightkeeper in the port of Moreton Bay. After this he was the first lightkeeper at Woody Island in the Great Sandy Strait (from 1 October 1867) and then at Sandy Cape since 28 April 1870. Simpson and his wife Jane (nee Williams, daughter of Robert Williams and Ann Lobb) were married in 1859 had 10 children; the last three (Charles, twins Edwin and Percy, and Edith Maud) were born while Simpson was stationed at Sandy Cape. Youngest daughter Edith was bitten by a snake and died aged 8 months on 12 January 1877, but it was the death of John Simpson that brought the family's stay to an end. John Simpson, on Thursday 20 July 1882, was out hunting wallaby in the afternoon and had just shot one with his doubled barrelled rifle. As he ran to secure the wallaby John tripped over a log and as he fell the stock of the gun smashed off and the gun discharged into his left breast. He died face-down on the spot and was found by his son Charles soon after. An inquest a week later found that it was an accident. Simpson left a wife and 9 children (Elizabeth, Helen, Martha, Fred, William, Fanny, Charles, Edwin and Percy) to mourn his loss. A grave was erected on the track from the house to the lighthouse, beside that of Edith. The graves and gravestones are still there today. The Simpson family moved out and Daniel Gorman and family moved in, taking official residence from 4 November 1882.

After a short stint at Sandy Cape, the Gormans moved to Inskip in 1886. Daniel Gorman was to be in charge of the Post and Telegraph at Inskip (from 16th April). At the end of August 1886 the Post Office was closed down and he was left just in charge of the telegraph (until 1st July 1890 when John Smith had that added to his duties). Three sons of Gorman - Daniel, Elliott and Robert became lightkeepers at Inskip and Hook Point once they reached adulthood.

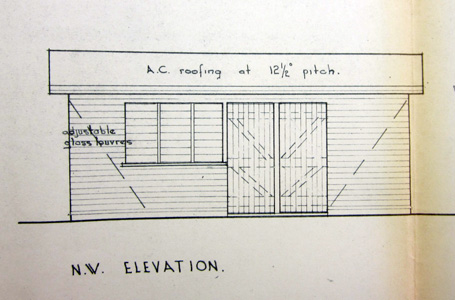

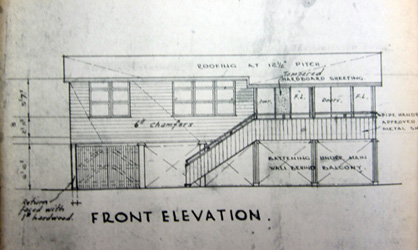

|

|

| Front elevation of the lightkeepers' cottages. The external walls were hardwood weatherboard; the veranda floor was of 4" x 1" hardwood and the internal walls were of 6" x 1" tongue and groove (T&G) pine. | Side elevation showing the store room at the rear. The floors were made of the same pine as the internal floors: 6" x 1" pine. The roof was galvanised corrugated iron. |

An unfortunate accident occurred in Jan 1887. The Pilot cutter was anchored at South White Cliff when at about 1am the steamer Balmain, coming down from the Mary River, struck her on the bow. The coxswain was unable to swim and drowned. Also in 1887 three cuttings had been dredged to a depth of 10 ft in the Great Sandy Strait and had been beaconed, but not lit, as there was no steam launch available to tend the lights. Consequently, all traffic along the coast for 30 miles was stopped at night, causing considerable annoyance to the coastal trade.

Two years later - in 1888 - James Turpin joined as a lightkeeper and Captain John James Hopkins as a boatman. James Turpin and his wife Hilda (nee Straudgrist) had three children with them: Lillian ("Lilly") Maria 4, Arthur Joseph George John Aggett (whew!) 2, and Elizabeth Emma 1. Their fourth child Clara Francis was born the following year. Captain John James Hopkins was an experienced ocean-going seamen. This was quite a step down for him: from master of a vessel recruiting black labour ("kanakas") from the south seas for the Queensland sugar trade - to a boatman at Inskip. Nevertheless it was a start and he rose rapidly through the ranks. He was born in London in 1860 and became a seaman at 14.

After quitting his kanaka trade he settled in Maryborough in 1880 and married Mary O'Leary four years later. Their only child Mary Ann was born the next year and arrived with them as a three year old at Inskip in 1888. Smith, Gorman and Reilly continued on, with Smith taking on the additional duties of Telegraph Officer Keeper (1 July 1890). In 1890 Peres left and was replaced by James E. Halliday (as boatman). As well John Dewar (boatman) and his wife Margaret took up duties. The following year (1891) the first pilot at Inskip - John Smith - died of apoplexy or a heart attack at Inskip (on 11 February) Smith's body was brought up by the steamer Llewellyn and interred in the Maryborough Cemetery.

Samuel Reilly took over Smith's Pilot and Telegraph Office duties (from the same day) for 10 weeks until Benjamin Nelson, the assistant Pilot from Normanton was appointed in his place on 27th April that year (he would continue in this role until 21 December 1893). Despite the cyclones and big seas, the lightkeeper's cottages at at Inskip Point remained in good repair.

|

In the distance is Hook Point, Fraser Island, taken from the beach at Inskip Point near where the original Pilots' and Lightkeeper's Cottages were located. The dangerous and deadly Wide Bay Bar is to the right. To the left on Fraser Island is where the Hook Point Lightkeeper's Cottage was once located. (R. Walding, 2009) |

Also in July 1890 a new channel had been buoyed and lighted across the Wide Bay Bar and when checked again the following year it was reported as maintaining its depth and direction. Now, in the Great Sandy Strait and Mary River, there were no less than 50 lights, most of which were leading lights burning by day and night. These lights kept two steam launches with their crews constantly at work attending to them; the Llewellyn, Norman, Ostrea and Diana were used for maintaining the lights and oyster fisheries in the Straits. As you could imagine - it was very costly and quite elaborate. The Department was keen to find another means of making the channels safe for a smaller outlay.

DEATH OF EMILY JANE REILLY

1891 In mid-1891 a terrible tragedy occurred at the Inskip Light and Signal Station. Samuel and Emily Reilly's daughter Emily Jane ("Jenny") was accidentally shot and killed by her younger brother William. The Brisbane Courier on Thursday 16 June 1892 carried the sad notice on the first anniversary of her death (also Maryborough Chronicle 15 June 1892):

The following are the depositions to the Magisterial Enquiry into the death of Emily Jane Reilly as reworded and reported in the Maryborough Chronicle - Tuesday 16th June 1891. I have compared them to the original depositions and despite the editorial changes, they give a reliable account. The original depositions are in the Queensland State Archives Inquest Files 36/190, 251-300.

REILLY.- In loving remembrance of our dear daughter, Jennie Reilly, who died at Inskip Point, on 15th June, 1891, aged 16 years. By her sorrowing parents. REILLY.- In memory of our dear niece, Jennie Reilly, who departed this life at Inskip Point, 15th June, 1891, aged 16 years. By her loving aunt and uncle. Pure, pure she was, as morning's earliest dew, Bright as its gem, but, ah ! as transient too. |

|

PHOTOS OF EMILY'S GRAVESITE

|

|

Emily Reilly's grave at Inskip Point. Note that there was a cross. Photo by Natasha Cooper, Kingaroy, 1994. Location: WGS84 is 25 48' 45.3", 153 03' 33.8". |

In July 2006, the Emily's grave was more deteriorated and the cross removed. The next year Council workers built a treated pine barrier to try to protect the site. (Marian Young, July 2006) |

|

|

| Dr Richard Walding at the grave of his Great Aunt Emily Jane Reilly. A fire had burnt many of the palings since the 2006 photo. A few months after this photo was taken a tree fell on the grave.The fence was built to keep the dingos out. There were many dingos at Inskip at that time and, in fact, that's the reason Samuel Riley had the loaded gun - "for the purpose of shooting a dog". (Photo Alan Marrs - Oct 2009) | Richard Walding at the gravesite. When the grave was prepared, it was located closer to the water. The Reillys thought this was a fitting place for Emily to look out over Pelican Bay. Since 1891, the changes in the shoreline have placed the grave much further inland. (Alan Marrs, Oct 2009) |

|

The quality of the original workmanship and care that went into the construction of the grave is evident from this photo: 4" x 2" hardwood rails and 1½" x 1" morticed hardwood palings. The treated pine barrier was a good temporary solution - if unsightly - to deter campers from taking the palings for barbeques and beach fires. But a better solution was needed. (Richard Walding, Oct 2009) |

|

| To find the grave, you need to head back out of Inskip along the main road until you come to the last set of rubbish bins on the left (next to the camping ground). On the opposite side of the road there is a steel pole acting as a gate to block entry into the old dump. If you step over the gate and head slightly to the left and walk along the old track to the dump (plenty of broken glass - wear shoes) then head left again through the trees for 2-3 minutes you should eventually find it. It is hard to find. Location: WGS84 is 25 48' 45.3", 153 03' 33.8" |

|

|

| David Lee of Caloundra visited the gravesite on Tuesday 8th May 2012 (this photo and one to the right). David said that it looked in good condition for a grave 120 years old, and that the fallen tree on it had been removed and the area kept clear. | David recorded the location as WGS84 25 48' 45.3", 153 03' 33.8" (Lee, May 2012) |

GOVERNMENT PLANS FOR PROTECTION AS A HERITAGE SITE

Plans are well underway by the State Government and Gympie Regional Council to manage Emily's Gravesite. The aim is to protect it from further destruction but not to make it a tourist attraction. You may be interested to read the letter from the Minister for Environment and Resource Management to the Acting CEO of the Gympie Council on 29 March 2011 to this effect (

click here). You may also be interested in an article by Gympie Times journalist Shelley Strachan on the gravesite, published March 17th, 2012, page 19 (click here). Professional advice on the care for Emily's grave was given by Paddy Watterson (the Principal Heritage Officer, Archaeology Team, Heritage Branch, Department of Environment and Conservation) on 4 March 2011. His four main points about heritage conservation of the grave site can be summarised as:

1. Maintenance is essential (sites such as these are more prone to vandalism if they are in a state of disrepair). 2. Do not unnecessarily remove original fabric (timber). The pictures seem to suggest an earlier wooden fence, which is consistent with what was commonly used in these contexts. You need to document the surviving fabric and if possible, reinstate the fence incorporating viable original elements. 3. Vegetation should be cut, not dug up. 4. A discrete marker [descriptive memorial plaque] is appropriate: the most enduring would be to have a small concrete plinth with an angled surface to facilitate water run-off. |

|---|

In May of 2012, a new Ranger with Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS) - Grant Phelan - was appointed to take on the project of the conservation and acknowledgment of Emily Jane Reilly's burial site. He is based at Rainbow Beach. Work began on the site on 22 May 2012. I'd like to thank Grant for his consultation. There is no intention of making this a tourist attraction or part of any heritage trail.

|

|

| QPWS Rangers clear vegetation around the grave site - as recommended by the Heritage Officer. (Grant Phelan, 22 May 2012) | The QPWS Rangers will try to ensure that any future fires do not destroy more of the grave site. The treated pine log fence will be removed during the conservation work. (Phelan, 22 May 2012) |

|

|

| On 1st June 2012 rangers built the new grave surrounds. I'm told their raised their glasses at the Rainbow Beach Surf Club that night in memory of Emily on the 137th anniversary of her birth (1st June 1875). Nice one! As well, a fisherman on holidays - Dave McQuaid - read about Emily's grave in the Gympie Times and placed a wreath of flowers there on her birthday. Thanks Dave! | The timber is treated spotted gum from the forest at Kin Kin (under a forestry permit) and sawn by Robertson Brothers Sawmill, Gympie. It has received a Lanotec (lanolin based) coating. The rangers will let it weather down and only re-oil every two to three years. (Grant Phelan, 2012) |

|

|

| The original fabric (timber) was too burnt and broken to be incorporated into the new structure as the Heritage Officer had hoped. It has been left there - at least for the time being. (Grant Phelan, 2012) | Detail of the bottom rail and palings. Machine work on the timber done by Graham. Carpentry for cross by Larry Shillig and carpentry for fence by Dave Palmer. (Grant Phelan, 2012) |

INSTALLATION OF THE PLAQUE

The plaque was prepared by Grant Phelan from an inscription written by Richard Walding - great grand-nephew of Emily Reilly. On Tuesday 7th August 2012 the QPWS Rangers attended the site to mount the pillar in cement in the sand. The plaque was affixed to a specially cut 250 mm x 150 mm slab of locally sourced and treated spotted gum with a lanolin preservative. I was pleased to be invited to attend the final stage of the restoration of the gravesite. On behalf of the Reilly family I would like to thank the Rangers for their fitting tribute to a life taken so young 121 years ago.

|

|

| QPWS rangers install the hardwood pillar on which the memorial plaque is mounted - 7 August 2012. (R. Walding) | Richard Walding, great nephew of Emily Reilly, was invited to take part in installing the pillar - 7 August 2012. (Linda Walding) |

|

|

| Richard Walding thanks the rangers for their work and talks about the circumstances of Emily's death. The Ranger Community Engagement - Grant Phelan - is to the right. He was responsible for the team managing and carrying out the last stages of restoration and gaining family involvement - 7 August 2012 (L. Walding) | The inscription on the plaque was suggested by Richard Walding at the request of Grant Phelan. (R. Walding) |

|

| L to R: Dennis Parton, Tony Moore, Grant Phelan, Richard Walding, Dave Palmer and Richard Whitney. (Photo: Linda Walding, 7 August 2012) |

UPDATE 7 AUGUST 2022 - 10 YEARS LATER

David Lee visited the site on 7th August 2022 and took these great photos.

|

| The gravesite is in great condition thanks to the care and attention of Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service rangers. The 7th August 2022 marks 10 years to the day since the gravesite was officially dedicated. (David Lee, 7 August 2022) |

|

| The cleared area has worked well in preventing fires from destroying the gravesite. (David Lee, 7 August 2022) |

OTHER GRAVES AT INSKIP POINT

|

Some of the graves that have been mentioned at Inskip Point over the years. |

My father Robert Walding recalls three of the four graves marked here. One of the two graves to the left (marked with crosses above) he said "was in the bushy part leading to Pelican Banks. It was complete with a cross and chain surround on low posts and we used to paint the chain and cross white". "Another grave was next to the coconut palm and fig tree near the house. Old-timers said this was a seaman's grave" (the coconut palm is in the modern-day roundabout). This is the grave of James ("Jim") Straightley Nolan (Gympie) who drowned early in the morning of the 11th February 1893 when the Daphne was wrecked on the Bar. He was buried at Inskip Point on the 14th by Samuel Reilly who telegraphed the Portmaster of the facts the same day.

As for Emily's Grave to the right he said: "In 1934, I remember looking for bush turkeys along the back shoreline at Inskip, about 200 yards past Bob's Bight, and about 100 yards into the bush from the mangroves' high water mark when I came across a grave. It was about 6 foot by 3 foot fenced with sawn hardwood timber about 2" x 1" properly spaced about chest high. There was no headstone - nothing else - to indicate who was buried there. I think the fence was erected to keep dingoes out. My mother said it was grave of her sister Emily - who died in the early 1890s". Charlie MacDonald - who was there from 1926 (as a 6 week old) to 1934 with his parents - lightkeeper Vic MacDonald and his wife Constance - recalls there were two graves on the left near Pelican Banks. Only Emily's grave has been located. On the 8th August 2012 I spent many hours in the undergrowth at the point looking for evidence of graves but none was to be found.

INSKIP POINT - 1892 ONWARDS

On the 8th October 1892, Benjamin Nelson was taken off Post Office and Telegraphy duties at Inskip and Samuel James Reilly given the additional task. Reilly continued in this role until Daniel Gorman's 17 year old son Elliot (born 1 April 1877 at Lady Elliott Island; notice the differences in spelling) took over on 13th March 1894 (which he continued to do even when the Post Office was closed in October 1907). For 1893 the staff were: Daniel Gorman (Telegraph Operator and Lightkeeper), Benjamin Nelson (Chief Pilot), Samuel J. Reilly (Coxswain and Boatman Pilot), Capt. John Hopkins (Boatman) and J. E. Halliday (Boatman). The relief lightkeeper at Hook Point was Henry James Sparshott who was down from his normal position as lightkeeper tending the leading lights at Mt Bramston over the south passage to Port Dalrymple at Bowen - and was to return to Bowen in November 1894.

The Argus, Melbourne, Thursday 16 February 1893

BRISBANE, Wednesday. With reference to the wreck of the schooner Daphne in Wide Bay, Coxswain Riley, of Inskip Point telegraphed to the port master yesterday as follows - "One of the crew of the wrecked schooner Daphne landed here on Saturday at 2 p m, after being 12 hours in the water. His name is Alex. Patience, and he considers that he is the only survivor. The body I picked up and buried was that of a passenger and the only name the informant knew him by was "Jim". There were seven, all told, on board the schooner when it was wrecked. The cargo consisted of 60 tons of general, 60 tons of coal, and a quantity of kerosene. The schooner was bound from Sydney to Dungeness. The survivor states that she capsized before he left her. She weighed anchor at Double Island at half-past 10 p.m., and struck and capsized at midnight on Friday the 10th inst. Nothing like her cargo or anything of value has been stranded here to date. |

The Hopkins family (John, the boatman, his wife Mary and daughter Mary Ann (8) left Inskip in 1894. Mary Ann had been attending school at Inskip and, in fact, John had been treasurer on the school committee. In 1895 J. McDonald was appointed Boatman in place of Capt. Hopkins who had been transferred to the Pilot steamer Llewellyn. Samuel Reilly's oldest son William Walter (now aged 18) was appointed to the crew of the Queensland Government Steamer Llewellyn at £5 per month from 1st Jan 1896.

The wage bill for the month of December 1896 tells the story: S. J. Reilly was Coxswain and Boatman for Inskip Point (£9.16.8) along with J. McDonald ((£8), Reilly was also given a foraging allowance of (£1) while aboard the pilot ship S.S. Norman. The lightkeeper at Inskip was Daniel Gorman (£8.16.8). Samuel James Reilly's son Samuel Stephen Reilly was now 18 and was appointed Assistant Lightkeeper for the Mary River and Sandy Straits (£4) along with C. Hume (£8.16.8) and Lightkeeper in Charge Patrick Farrell ((£14, an engineer). The three of them were also given £2.10.0 per month for attending lights at White Cliff. [Reference: Qld State Archives, Register of Salaries Paid, 1896-1907, Item No. 8797].

LIGHTKEEPER'S TASKS

The duties of Lightkeepers has varied over the years but their core responsibilities have remained the same. In brief:

|

The lightkeepers at Inskip Point were in contact with the keeper from Hook Point - who at this time was John McMahon. Hook Point was more isolated than Inskip and because there were no pilots stationed there was quite a lonely place. John McMahon asked Samuel Reilly to approach the Department about the state of the lightkeepers cottage which had been erected in 1878. On 4th March 1895 Reilly wrote suggesting that they shift the house as erosion was taking its toll. An inspector visited soon after and suggested a new house be built - which it was done - in 1906. The big news for Samuel Reilly at this time was that he was appointed to be a Sub-Inspector of Fisheries at Inskip - as well as his coxswain pilot duties (from 18 November 1896).

|

A small row boat is used to take goods and passengers to and from Inskip Point aboard the steamer Llewellyn. In the distance is an ocean-going liner possibly awaiting a Pilot. It is not certain where this photo was taken; possibly Inskip Point or Moreton Island. (JOL 84-1-1) |

On the 23 November 1896 Reilly was appointed "Pilot Coxswain" at Inskip Point. Samuel Reilly's monthly wage in the 1890s was made up of a base salary as Coxswain & Boatman of £9.16.8, and the following allowances: Attending the lights at White Cliffs £2.10.0; Lightkeeper for Mary River and Sandy Straits £4.0.0; Sustenance Allowance on SS Norman, £1.0.0, making a grand total of £17.6.0 per month or £208.0.0 per annum (which is about $25,000 pa in 2009 dollars). The Lightkeeper at Inskip Point - Daniel Gorman - was getting £8.16.8 pm while his counterpart at Double Island Point - George Byrne - was getting £14.11.8 pm but Byrne had two assistants: S. Kenny (£9.16.8 pm) and John Dewar (£8.16.8 pm).

Other people were working alongside Reilly on various tasks were: Keeper in Charge of the Leading Lights on the Mary River (Heads) and Sandy Straits - P. Farrell (£14.0.0) and assistant C. Hume (£8.16.8). There was no lighthouse as such at the Mary River Heads but an unattended illuminated "Lead" or "Leading Light" that assisted with navigation. As with other leading lights the men attending it would check and refuel it regularly. These men also received an allowance for attending the White Cliff Lights of £5.0.0 and £2.10.0 respectively. Reilly, at Inskip, also had an assistant Coxswain - J. McDonald - who received £8.0.0 per annum. These wages may seem low but, like Reilly's, there would have been other allowances paid; John Dewar, for instance, worked mainly on the Woody Point Light. [QSA Item 8797].

A sad note appeared in the Maryborough Chronicle at the end of 1898. There appeared the obituary for Mary Ann Hopkins, aged 14, daughter and only child of Captain and Mrs Hopkins (formerly boatman at Inskip Point). Mary Ann had died in Maryborough from "scarlatina" (Scarlet Fever). Captain Hopkins eventually became Pilot for Maryborough (1911) and was also Captain of the steamers Albatross, Excelsior and Woy Woy. He retired in 1922 and died on 7th November 1927 at the age of 67, predeceasing his wife Mary. His obituary appeared in the Brisbane Courier 10 November 1927. Back to Inskip Point.

In March 1899 Samuel Reilly's son William was transferred from the Llewellyn to become Lightkeeper at Mary River and the Sandy Straits (and to tend to the White Cliff light for which he received an extra £3.15.0). In September 1899 Reilly's next son Samuel Stephen Reilly (aged 21) was appointed as "Boy" to the Inskip station at £5 per month. In February the next year William Reilly was transferred out of the district. The regulations of the Department forbade any son of a Lightkeeper or Pilot from remaining with the family at a lighthouse or light station after turning 19 years unless permission was granted.

|

A car ferry now runs daily between Fraser Island and Inskip Point. This is the spot on Inskip beach where the QG supply ship Llewellyn would load and unload goods as shown in the photo above. A rowboat was needed to get out to the steamer. (Richard Walding, 2009) |

A YACHTING CRUISE

In April 1902 the Reilly and Gorman families at Inskip Point had special visitors. The visitors were not anything special to the Inskip Point fraternity but only special because the leader published a booklet on his adventure - "A Yachting Cruise of the Sandy Straits". The visitor was John ("Jack") N. Devoy, secretary of the Castlemaine Brewery and manager of the legal firm Quinlan, Gray, and Co., Limited.

He was born in Ireland and came alone as an eight-year old passenger aboard the British sailing ship Chariot of Fame in 1866. By the age of 20 he was a member of the No. 1 Battery Queensland Volunteer Artillery and became an excellent shot. It was his interest in rowing and boating that eventually lead him to Inskip. At the age of 21 he became am Intercolonial champion rower for the Brisbane Rowing Club, competing successfully in many events held at the regatta bend in the Brisbane River. He was soon the club president and life member. His rowing friends formed a "The Up-the-River Picnic Party" and would go on all sorts of boating adventures.

In 1891 he was appointed as secretary to the Castlemaine Brewery and soon after married Annie Fitzgerald - the niece of the man who was to become Mr Fourex of the brewery - Paddy Fitzgerald. That's a long introduction but it sets the scene for their story. In 2009, I decided it would be good to retrace the voyage of Devoy's boat Ide through the Sandy Straits. With two companions, Alan Marrs (Pilot and Coxswain), John Oates (boatman) and me as photographer, we visited as many of the spots mentioned by Devoy in 1902.

|

|

Me and Alan Marrs (right) - just near Garry's Anchorage on Fraser Island, south of White Cliff. This anchorage was named after aboriginal tracker Garry Owen in the late 1800s (see report later on). (Walding, 2009). It is with great sadness that I must record the passing of our great friend Alan William Marrs on 2nd September 2023. See below. |

Commodore Alan Marrs and boatman John Oates passing along Boult's Gutter. Whew, that's not where the map says. (Walding, 2009) |

Alan's wife Lee quoted the poet Nicholas Sparks in a memorial on 7 September 2023: "Love is more than three words mumbled before dinner. |

The Ide was a 26 ft yacht with a 2 ft draught and four berths. The crew was Jack Devoy (logkeeper and photographer), George (Commodore), Alec (scientist, artist and musician), Fred (deckhand), St John "Sin Jin" (chef) and they met on the William Collin & Sons jetty in Brisbane at 8pm on the 23rd April 1902 and watched the 4 ton yacht being hoisted aboard the cargo ship Flinders. The following morning they passed Double Island Point, over the Wide Bay bar ("calm"), past Inskip Point "cypress pines and firs".

|

|

Looking south towards Double Island Point. Jack Devoy and his party had their boat Ide aboard the Flinders when this photo was taken. (Devoy, 1902) |

View of Double Island Point from Rainbow Beach. You can see why Cook thought it was two separate islands. (R. Walding, 7 Dec 1993) |

|

|

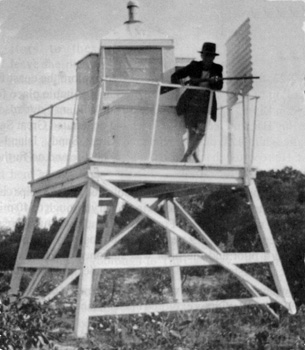

The Ide anchored at Inskip Point as the crew come ashore in a dingy - 24 April 1902. Photo: Jack Devoy, 1902. Annotations by Robert Walding 1934. |

The same beach at Inskip Point with Snout Point, Fraser Island in the distance - 4th October 2009. (Walding, 2009) |

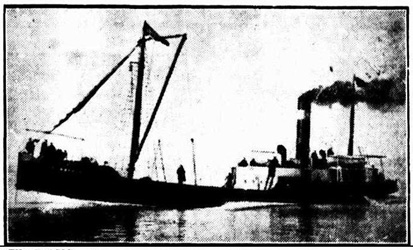

The steamship in the distance in the photo to the left is on it's way down the Sandy Straits from Maryborough "running down" the Inskip Point leading beacons for Sandy Straits and would then continue mid-channel to pick up the Inskip Point bar leads about one mile along the beach towards the right of the photo. It would then pick up the Hook Point leads on Fraser Island's east coast which finally would take them through the deepest part of the shifting sands of the Wide Bay Bar, to the open ocean. By the afternoon of the 24th April (1902) the Flinders had reached White Cliff - about half way up the Sandy Straits - where the Ide was lowered into the water. This is where the yachting cruise began and because of tides and winds the Ide's progress was somewhat of a zig-zag. Nevertheless in the 17 days available the Ide visited Mary Heads, Picnic Islands, Bogimbah Mission Station (Fraser Island), Judd's Camp, Inskip Point, Tin Can Bay, Figtree, Leftwich & Sons oyster grounds, Poona, Shell Island, North Cliff, South White Cliff, Mary Heads and home to Brisbane on the 9th May.

|

|

Launching the Ide off the Flinders at South White Cliff - Sunday 25th April 1902. When the Flinders ceased visiting Maryborough in 1920 the passenger trade almost died (although cargo ships still came). (Devoy, 1902) |

Here we are launching our boat at Tuan Creek because the tide was too low at Poonah Creek. On Saturday 4 May 1902 the Ide left Tin Can Bay and headed for Poona but the tide was too low for them to land there. (Walding, 2009) |

|

|

| 30th April 1902: The Pilot & Receiving Officer Samuel James Reilly and his family at Inskip Point. With him is his wife Emily (nee Compton) and some of their 17 children. Back row: Mildred (15), James (14), Ada May (12), Violet (10); Front row: Blanche (19), Myrtle (8), Pilot Samuel James Reilly, Pilot's Wife Emily Reilly (nee Compton), Cornelius (6). Other children include: William Walter (25), Samuel Stephens (24), Maud (22), George (19), Harold Wade (9). By the time this photo was taken three children had died: Amilia ("Milly") Beatrice (1877 at about 10 months old), Herbert Winterley (in 1882, aged 11 months), and Emily Jane (1891 at the age of 16). (Devoy, 1902) | Pilot Reilly's house with Telegraph Office to the far right (1902). The soil in and around the houses was sandy with little grass but a lot of rushes, bracken and hardy ferns. The trees were mostly cypress pine. On 15th June 1891, Reilly's oldest daughter Emily Jane (16) was accidentally shot by her 13 year old brother William Walter Reilly and died in her father's arms next to the tree at the front gate in the photo above. She was buried about 250 m away. The unmarked grave is there today (as described earlier). After 1902 the pilot's and boatmen's cottages were removed and only the lightkeeper's cottage remained (on the far left in the distance). (Devoy, 1902) |

|

|

The Ide at Leftwich's Oyster Lease - 3rd May 1902. He was one of the first to take up the Government's option of buying oyster leases. (Devoy, 1902) |

Leftwich & Sons oyster lease area outside Tuan Creek. Nothing left of the oyster operation now. (Walding, 2009) |

|

|

Some fishing for the crew of the Ide at South White Cliff at 8am Sunday morning on the 5th May 1902. (Devoy, 1902) |

South White Cliff is just to the left of centre, now overgrown. The Ide was dropped off from the Flinders here on 25th April 1902. (Walding, 2009) |

|

|

| The Ide moored in Yankee Jack Creek on 3rd April 1902. The creek was named after Jack Piggott who harvested timber for the Pettigrew's Dundathu Mill near Maryborough in 1863. (Devoy, 1902) | John and Alan - up Yankee Jack Creek. "Yankee Jack" Piggott was speared and killed by an aborigine at Rooney's Point in 1864 where it was suspected that he had gone to engage in blackbirding (the kanaka trade). Alan is telling his wife that he has a flat tyre and is not having fun. (Walding, 2009) |

|

|

The entrance to Yankee Jack Creek was hard to see. (Walding, 2009) |

A small hut on Moonboom Island. (Walding, 2009) |

|

|

The Ide's crew - fishing at Tin Can Bay - 3rd May 1902. (Devoy, 1902) |

Fishing boats today at Tin Can Bay - 2009. (Walding, 2009) |

|

|

The Ide's crew having a rest at Garry's Anchorage - 30 April 1902. (Devoy, 1902) |

We stopped at Garry's Anchorage for morning tea. (Walding, 2009) |

|

|

The Ide off Poona - Thursday 1st May 1902. They couldn't land because it was low tide. (Devoy, 1902) |

Looking over to Fraser Island from Poona at high tide - 2009. (Lee Marrs). |

|

|

Poona at high tide looking south east to Inskip Point. (Lee Marrs) |

You can launch a dinghy from Poona when the tide's in. The Marrs' bungalow in the background. (Lee Marrs) |

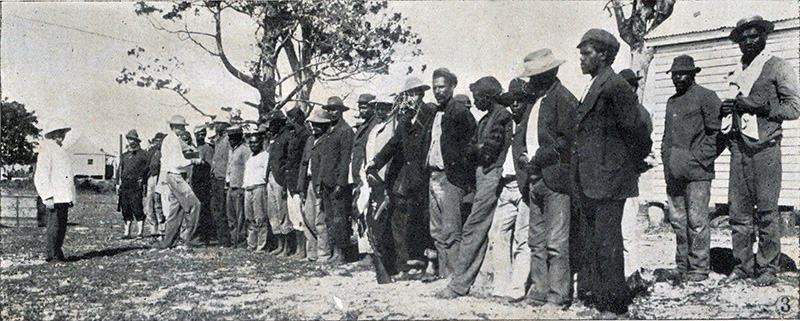

WHAT DEVOY DIDN'T MENTION - THE DISPOSSESSION OF THE BUTCHULLA PEOPLE

When Jack Devoy visited Fraser Island in 1902 he stopped off at the Bogimbah Mission settlement. This was located on Bogimbah Creek about 10 km north of White Cliffs (about 8 km north of where Kingfisher Bay Resort is today). It could only be accessed by a tidal creek and was skirted by a mangrove, infested with sand flies and mosquitoes. The camp was set up by the Government to intern indigenous (Butchulla) people who had been deemed to have "reached a deplorable stage of degradation, being completely demoralised by drink, opium, disease, and intermittent periods of semi-starvation" from the Maryborough district. By the time Devoy visited the camp it had been handed over to Anglican Board of Missions and had become an incarceration facility for indigenous people from around Queensland. Conditions at Bogimbah were dire, with inadequate shelter and rations. This was a shameful act perpetrated on the indigenous people of the region but perhaps Devoy didn't recognise this. He happily photographed aboriginal people in their awful camp and then he moved on. The captions on the next set of photos are by Jack Devoy.

|

|

| "A typical native residence at Boggimbah" page 20 | "Molly and I and the Baby" page 21 |

"AT THE MISSION STATION ON FRASER ISLAND"

|

|

| "Some of the boys at home" page 29 | "More mission members (one of the men is holding a tow-row, or native fishing net". |

|

| "Serving out the tobacco ration to the mission boys" page 29 |

|

| Devoy's caption: Some more of the native "residences" page 23 |

Two years after Devoy's visit, the camp was disbanded when most inhabitants were sent to various other Queensland missions mainly Yarrabah near Cairns and Durundur near Caboolture. However, some Butchulla inhabitants remained on the island, living on the back beach and their descendants are there today.

|

|

Big Woody Lighthouse. The Ide reached there in the afternoon of the 26th April 1902 and did some rabbit shooting the next morning. There were two principal lights on Big Woody Island. (Devoy, 1902) |

Big Woody Lighthouse - 2006. (photo courtesy of Marius Coomans) |

|

|

| We didn't make it to Big Woody Light as the strong NE wind was making life difficult so I went back in August 2010. (L. Walding) | The northern tip of Big Woody Island (R. Walding, 2010) |

|

|

| North of Big Woody Island whales came up to the boat. See the barnacles on his flipper. (R. Walding) | They were so close you could easily see the blowhole. (R. Walding, 2 August 2010) |

|

|

Supplies being taken to Hook Point light and signal station from Inskip Point. The Ide again dropped in on the Reilly and Gorman families on the 2nd May. The Ide's logbook said "Inskip Point - Commodore departs for Brisbane on passing ship. Quiet rest at Inskip for rest of day". (Devoy, 1902) |

Two ferries takes cars and supplies over to Fraser Island from Inskip Point. (Walding, 2009) |

NOTE ABOUT GARRY'S ANCHORAGE

|

'Garry's Anchorage' |

In several of the photos above, Garry's Anchorage or Garry's Landing gets a mention. This feature was named after Garry Owens - a full-blooded aboriginal tracker from the Butchulla people - the traditional custodians of Fraser Island. His name was possibly taken from the name for Fraser Island "Kgari". His son Isaac Garry Owens was one of the last full-blooded Butchulla. He died at Hervey Bay in 1977 aged 62, a bachelor like his elder brother. He made a statement on his recollections of Fraser Island to the Fraser Island Environmental Inquiry in 1975 and also accompanied the FIDO veterans tour to Fraser Island in September 1976. Ike Owens loved Fraser Island - his ancestral home. This verbatim and signed statement is one of the few recorded by a Fraser Island Aboriginal with 20th Century island connections. He talks about meeting the lightkeepers of Inskip Point.

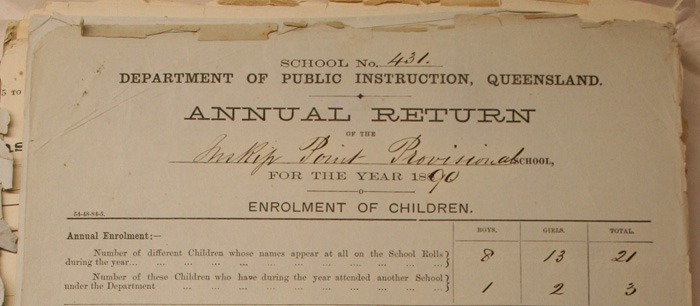

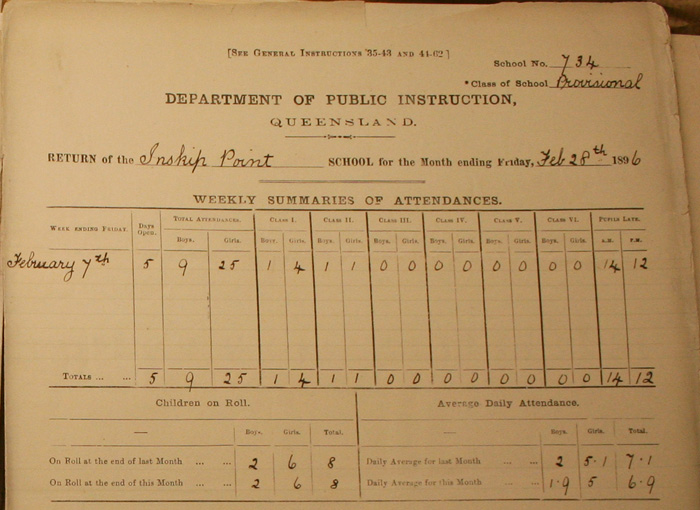

SCHOOLING AT INSKIP POINT

The Queensland State Government, like governments everywhere, will provide schooling for children if a need can be established. The State Education Act of 1875 established a new Department of Public Instruction, which was charged with the duty of providing free, secular and compulsory education for children between the ages of six and twelve years. Provisional schools were established where an average attendance of between twelve and thirty pupils could be maintained, and required that local people provided a suitable building at their own expense (over 30 pupils and the Department would establish a fully funded "State" School). Such was the case at Inskip Point.

Pilot Samuel James Reilly believed he had met the need for a Provisional School when he advised the Department of Public Instruction in October 1883 that there were eleven students ready for instruction the following year. While the Department paid for the maintenance of State schools, the School Committee was responsible for maintaining a Provisional school. The only expenditure incurred by the Department in approving a Provisional school was in paying the teacher's salary and providing a minimum of expendable supplies to keep the school functioning.

Reilly nominated eleven students with the prospect of more to come from the large families present at Inskip - nearly all of which had under-school-age children that would be enrolled in the not-too-distant future. He named the following children from the five families at Inskip: his own daughter Emily Jane Reilly aged 8 and her siblings William 6, Samuel 5, Maude 4. The others were the sons of Lightkeeper George Byrne, namely George Thomas Byrne 8, Reginald James Byrne 6, Mary Anne Smith (dau of Pilot John Smith) 6; John Anderson 6 and Charles Anderson 4, sons of Charles Anderson; Ellna Peres 5 and Hilda Peres 4, daughters of Frank and Hilda Peres, giving a grand total of eleven students. On 29th October 1883 Queensland Portmaster George Heath in Brisbane wrote to the Minister for Education Samuel W. Griffith (after whom Griffith University was named).

A school room had been built by the residents and he was able to advise that the Lightkeeper George Byrne would provide lodgings. He also told Sir Samuel that the local timbergetters could also take advantage of the school. The Provisional school teacher was usually an unclassified teacher who was not provided with a residence by the Department, and who received a salary less than that of the lowest classified teacher. Such teachers often had a barely adequate education themselves, and little or no training, but some of them were well-educated people who had been unsuccessful in other occupations, or educated women forced to provide for themselves.

These teachers often had to work under very primitive conditions, a roof that didn't leak and a wooden floor in the classroom being above average appointments. Their annual salary, just under ₤40 pa at the time, was less than a labourer's, and living accommodation was basic in the extreme. Yet they educated the pioneers' children, and most of them were women. It was widely regarded that women teachers were better than their male counterparts, and in 1881 District Inspector John Shirley wrote:

The Provisional school teacher has neither the comfortable buildings nor the suitable furniture of the State school teacher; he works under many difficulties and with little encouragement from those among whom he is placed; yet he does cheap, useful work for the State, and work that could not well be done otherwise. For such work a female teacher is much more suitable and more readily obtained than a male teacher, and, as a matter of fact, but few Provisional schools gaining credit by inspectors are taught by men. |

John Shirley's use of "he" when it was nearly always "she" in Provisional Schools is meant to be an inclusive pronoun. To the pleasure of the Inskip Provisional School Committee (Reilly, Byrne, Smith and others) new Regulations came into force in 1892, in which the Department had altered its policy, agreeing to pay for up to half the cost of the building and furniture for a Provisional school, if it were built on Crown land. And Inskip was Crown Land.

Their first teacher was 22 year old Mary Garsden from Wagga Wagga, NSW who began teaching as a 16-year old pupil teacher at West End State School in Brisbane. She taught began on 21 Jan 1884 but her "violent headaches" from the sea air were too much for her so she resigned to 30 April 1884 who resigned on 29th March that year to get married. The conditions at the school would prove a disincentive to teachers to stay long as Inspector John Shirley prophesised.

The rapid population growth in Queensland in the 1880s and 1890s saw the number of schools double. This situation strained the colony's limited education budget and created problems of inadequate teacher supply and training as mentioned above, a proliferation of poorly equipped provisional schools, and a perennial teacher housing problem in rural areas. These problems were exacerbated for the isolated lighthouses of Queensland. However, these problems should be kept in perspective: despite the difficulties, Queensland educators achieved the considerable feat in bringing basic literacy to most Queensland children in the last decade of the 1800s.

On 7 July 1884 Margaret Kenny aged 41 was appointed but her services were terminated after 3 months due to poor enrolments (4 boys, 2 girls). She was troubled by a drunken husband, "now dead" which made the Department anxious about her situation anyway. She was shifted to Bustard Head Lighthouse (about 250 km north of Maryborough) before being transferred down to Double Island Point Lighthouse - almost a stone's throw from Inskip.

Next was 22 year old Greta Herley who arrived on 5th Jan 1885 to teach 14 students - 9 boys, 5 girls - (she had arrived from Ireland one year earlier and this was her first teaching job). She left at the end of the year and was sent to Glastonbury Creek State School just west of Gympie - about 100km away.

In this all-too-familiar procession of teachers, next was Mrs Teresa Bridget Sullivan who arrived 1st Jan 1886 to teach 22 children (14 boys, 8 girls). Finally, the Department had provided an experienced teacher and one described by them as an "exceptional teacher, superior to most female teachers". She had arrived from England 10 years earlier and took up teaching at Nudgee Orphanage (just north of Brisbane) and then Tamborine State School in the hinterlands behind the Gold Coast to the south of Brisbane. At this time she married Michael Sullivan in April 1882 and became Mrs Teresa Sullivan.

By now the families providing a steady source of enrolments had grown: In 1888 the Reillys had ten (Emily, William, Samuel, Maude, twins George and Milly, Blanche, Amy; Ethel and Mildred); John Smith still had his only daughter Mary Anne at school; the Gormans had ten including two sets of twins aged 9 and 14 years; the Turpins had three; and Boatman John J Hopkins and his wife Mary were also there. Teacher Mrs Sullivan (nee Flanagan) had a total of 14 students to teach from ages 5 to 12 years old. Committee member John Smith was not happy with her professionalism: he reported her to the Department for being drunk and the committee asked for her dismissal. They changed their minds soon after and blamed "that useless skunk of a husband" on her problems. She left on May 31st 1886 anyway. But they gave her a beaut going-away concert and afternoon tea. Mr Turpin sang a plantation song and was assisted by Mr Gorman, "in negro costume" to perform the farce of "Professor Slocum" and his assistant.

Her replacement - the fifth teacher in 3½ years was Mrs Clara F Cafferky, aged 20, who started on 2nd May 1888 with 19 students (8 boys, 11 girls). She had come from Galway Ireland and was living in Ipswich to the west of Brisbane. The Inspector noted that her teaching was "fairly satisfactory", but there was friction between her and John Smith (wouldn't you know it). The Inspector agreed that her tongue was "an unruly member" but she stayed on until the end of 1889. In that year there were 9 boys and 8 girls enrolled.

|

Annual Returns are held at the Queensland State Archives at Runcorn, Brisbane. In 1890: 7 boys and 11 girls. |

Finally - a man - William George Reeve - an Englishman no less was appointed on 24th March 1890 to teach 21 children (8 boys, 13 girls). His annual salary was £54. He didn't last much longer than the other despite being more difficult to obtain (in the Inspector's words). The Inspector wasn't too happy with Mr Reeve; he said that no progress had been made and that the class was "retrogressive". Presumable the inspector meant that the class was going backwards - no easy task for any teacher to have students unlearn things.