|

| Sunset over Toorbul Point viewed from across Pumicestone Passage, Bribie Island, Australia. The Toorbul Radar Station was on the lookout for enemy planes in these skies during WW2. It was located 5 km inland from the opposite shore. |

When The US submarine fleet arrived in Moreton Bay destined for the Port of

Brisbane in 1942, it became even more imperative that the wartime defences of Moreton

Bay be upgraded. Extra gun batteries were installed by the Army on the nearby

islands and mainland and the Royal Australian Navy installed indicator loops,

antisubmarine booms and controlled minefields in the bay. The Royal Australian

Air Force was responsible for the operation of a number of radar stations in the

area. This webpage deals specifically with the Toorbul Radar Station No. 210

about 5 km inland from Toorbul Point. Indicator Loops (long lengths of armoured cables laid on the seabed in

shipping channels designed to detect submarines passing overhead) are dealt with

in my

Indicator Loops

around the World (Home Page) and other Moreton Bay fortifications are in my

Moreton Bay Defences web page.

|

|

|

| Moreton Bay is in Southern Queensland near Brisbane | The Toorbul Radar Station is 5 km to Pumicestone Passage |

|

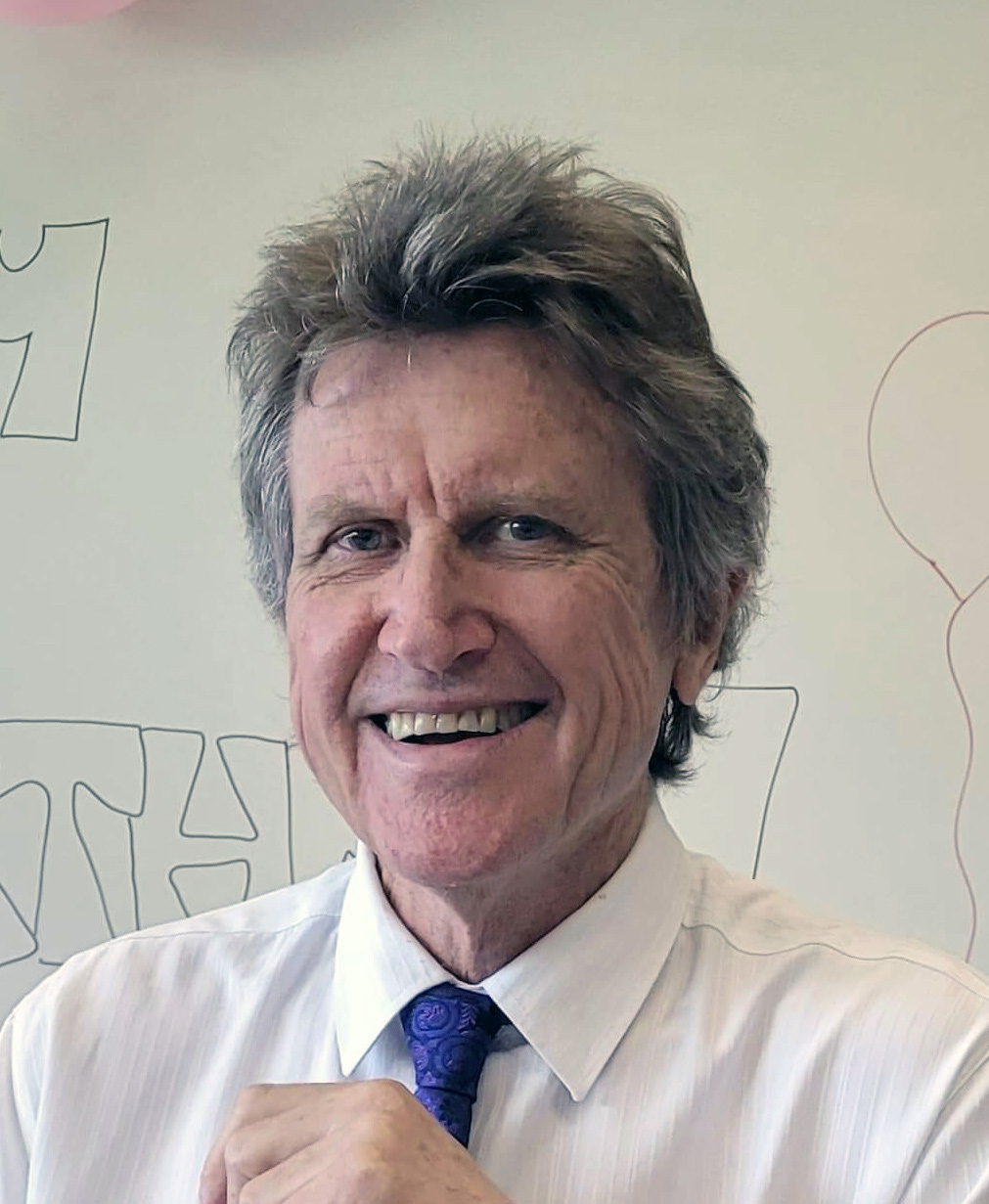

If you have any feedback please email me: Dr Richard Walding Research Fellow - School of Science Griffith University Brisbane, Australia Email: waldingr49@yahoo.com.au |

|

I'd like to thank the following people for help with this webpage:

Ldg Aircraftman Lionel Gilbert of Armidale NSW Ms Elizabeth Parry-Okeden - daughter of the former property owner Sgt Ed. Simmonds, 1RIMU, of Westhaven, NSW Ldg Aircraftman Alan 'Herman' O'Rourke of Blackburn, Victoria Ms Margaret McNaught, Local History Officer, Moreton Regional Council, Qld. |

LINKS TO MY RELATED PAGES:

Moreton Bay Defences

How an indicator loop works

SIGNIFICANCE

The former RAAF Radar Station No. 210 at Toorbul, comprising remains of

the RAAF radar installation is a significant example of Queensland's

participation in the WW2 network of air warning radar, established in

strategic locations along Australia's coast during World War II. It is one

of nine 'Advanced Chain Overseas' (ACO) radar stations established on

mainland Australia using British imported ACO radar. Its setting

demonstrates the importance of Brisbane's industrial region, as a major port

for US submarines and as the training ground for forces prior to and during

the south-west Pacific campaign against Japan. The site has potential

to yield further information about Australian coastal defence efforts during

WWII and the use and development of radar technology by Australian

physicists and engineers. The Radar Station 210 is of State significance for

its association with the RAAF which was given responsibility for the

nation's air warning defence operations during WWII and to ex-service RAAF

and WAAAF personnel that served during WWII. It has strong associations with

the role of women WAAAF who served as radar operators during WWII. It has

potential to yield further information about Brisbane and Moreton Bay

defences during WWII and its role in the network of the nation's air warning

defence during this period. It is a reminder of Queensland's role in the

introduction and development of radar technology during the war. It is

pleasing to note Moreton Bay Regional Council has an interest in this site.

Today the properties are in private hands.

|

| Toorbul Radar Station - mockup photo showing the height and approximate shape of the towers. The igloos shown in the photo are 3.8 m tall and the towers are about 12 times that (43 m). The closest is the Receiving (Rx) tower. These towers were demolished in 1946 and sold for scrap metal and timber. |

HISTORY

In February 1939, the British Committee of Imperial Defence shared information

about radar to Australian, New Zealand, South African and Canadian scientists in

London on the understanding that these Commonwealth nations would undertake

further research and adapt the new technology for the particular defence

requirements in their home countries. In August 1939, the Australian

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) approved the creation of

the Radiophysics Laboratory Board concealed in the University of Sydney. In May

1941 Wing Commander Albert George Pither was put in charge of RAAF's radar

operations. Pither was in Britain, studying radar when the technology was put to

use during the Battle of Britain in 1940. He developed a plan to surround

Australia with a 'home chain' of radar stations based on his experience in

Britain. On the 7th November 1941, one month before the attack on Pearl Harbour,

the RAAF was given full responsibility for Australia's early warning radar

operations and adopted Pither's radar defence plans. The British-made Advanced

Chain Overseas (ACO) radar installations were distinguished by robust towers

capable of withstanding hurricanes in the Far East. These radar installations

were regarded as sophisticated, complex and at the time, very expensive at an

estimated cost of

£21,000 ($1.2

million in 2009 dollars). It took several months to construct and calibrate an

ACO radar system and the sheer size of the transmitter and receiver towers made

them difficult to camouflage. The Toorbul Station was constructed by men from

the Civil Constructional Corps (a division of the Australian Allied Works

Council). Specialist RAAF and British RAF personnel installed and calibrated electrical and radar

equipment. It is interesting to note that as many Australian industries were

affected by a shortage of physicists during the war, the introduction of radar

enticed many physicists to abandon their degree courses to obtain training in

radar for the RAAF.

|

|

| Radar Operator Lionel Gilbert on leave from Radar School, Richmond, NSW. Taken at his family home in Burwood, Sydney, July 1943. His mother's first experience with a Kodak Box Brownie camera. | Four teacher-trainees of Sydney Teacher's College on their RAAF enlistment day, mid-June 1943. All became Radar Operators. L to R: (initial Radar Station shown): Eric Smith (Nelson Bay), Ken Edden (Townsville), Doug Beard (Gabo Is.), Lionel Gilbert (Toorbul). |

The Toorbul Unit itself was formed at Sandgate on 20 September 1943 and moved to its

radar site at Toorbul on 27 October 1943 under the command of 23 year old FlgOff Athol George Price of the RAAF

who was fresh out of a 6-month training course at Sydney Uni under Professor V A

Bailey, set up to train officers for the RAAF in the new radar technology. Price

was thus known as one of the Bailey Boys. Accompanying Price were Ldg Aircraftman Gordon Felton and Sgt

Gordon Clarke as Senior Radar Operators recruited from the Darwin ACO Station

257RS. The radar equipment had

arrived at the site on 7th October 1943 and on the 18th of that month the 1RIMU

installation party arrived.

By November 1943 Toorbul Radar Station

No. 210 was still incomplete and heavy rain which rendered both camp and the radar

station very boggy.

Spring 1943 was the 3rd wettest Spring in Brisbane since records began in 1847.

December was worse with 15" of rain for the month - the 3rd wettest December on

record.

Installation of equipment was complete by 15th January 1944.

The Station became operational at 1100 hours on 4th March

1944 with a staff of 1 officer and 31 ORs. On 21st January 1945 operations had

been reduced to just one watch (0530 to 1130 hrs) daily, requiring the loss of 2

Radar Mechanics (1 FltSgt, 1 Cpl), 8 Radar Operators (1 Sgt, 2 Cpls, 6 Aircraftmen

(ACs)) and 2

Guards (2 ACs). The station was off air from 4th to 11th February 1945 for

maintenance. Operations ceased at No. 210 Radar Station on 31 August 1945 on a

care and maintenance basis and the unit closed on 13th February 1946. The unit was disbanded on 21st February

1946. Formation Order AFCO B359/43; Disbandment Order AFCO B132/46.

Note: originally, in November 1943, it was planned to have 9 RAAF men (1 Officer, 3

Sgt and 5 ORs) and 22 WAAAF women (1 Off, 2 Sgt, 19 ORs) but this never came to

pass (see note below).

Note regarding WAAAF: The roles carried out

by personnel at many of the radar stations in Australian were delineated by

gender with airmen serving as mechanics and airwomen serving as operators. The

WAAAF (Women's Australian Auxiliary Air Force) came into existence in February

1941 amidst some controversy and resentment. However, recruitment of (WAAAF)

radar operators began in May 1942 after the success of WAAF radar operators in

Britain. An order on 6 October 1943 made it clear that WAAAF personnel would not

be sent to the Toorbul station 'until suitable accommodation was available'. This

never happened and the only time WAAAFs were at the Toorbul Station was for a

dance in the Mess hall. The WAAAFs were sent up from the Southport Radar Station

(209RS) for a social gathering and a dance to help lift the morale of both stations.

Radar Operator Lionel Gilbert recalled "I don't dance; I went to bed early that

night".

The property owner was WW1

serviceman Capt. Uvedale Edward Parry-Okeden MC, MID, a Gallipoli veteran who

greatly enjoyed the 'intrusion'. Servicemen, both Australian and later American,

would be invited to the Parry-Okeden house for afternoon tea and sometimes

dinner. He would keep the men enthralled - particularly the Americans - with his

tales of working in the Wild West in the late 1800s, befriending lawmen Wyatt

Earp and Bat Masterson in Kansas. Eggs were a rarity in a serviceman's diet so

Mrs "May" Parry-Okeden's curried eggs were a particular favourite. Dances were

held on the verandah and 'deck' tennis played nearby. Their daughter Elizabeth -

18 at the time - was a hit with the men but Capt. Parry-Okeden was sure to keep a

watchful eye on her and her visiting girlfriends from the boarding school in

NSW. More background on the family's relationship with the military may be found

on the Parry-Okedens at Toorbul website.

|

|

| Elizabeth Parry-Okeden (right) and friend Sue Rigby in front of the mango tree, January 1944 | The only sign that the Ningi homestead was ever there is the mango tree under which Elizabeth Parry-Okeden did her correspondence. It is now 8 metres tall. |

|

|

| The Parry-Okeden family at Ningi house, Toorbul, 1942 | The mango tree now provides shade for the Bishop's cows. Pancho is a young bull who is a bit camera-shy. |

Recounting the initial set-up of the Radar Station, Dr. Lionel Gilbert

said:

Our sergeant (radar) operator at Toorbul Point was Gordon S. Clarke. There was much to be done while the station was being prepared to become operational. A camp had to be established in the bush and roads made to service it. On a nearby flat, rather swampy, area stood the great towers of the ACO transmitter and receiver. It was crucial to complete the road from the camp to the station. Thirty inches of rain in three months made the digging relatively easy and the road critically important. We took it in frantic turns on a couple of spades - digging deep gutters from which the overburden was cast up to form the crown of the road. We were busy with the road-making, and also with clearing the camp area of combustible forest litter, so that admin, airmen’s sleeping quarters, the mess and cookhouse, etc, all of wood, would be out of fire risk – but at the same time, the cover of the natural forest was essential. The two towers and their accompanying igloos were however “unprotected” by our tree cover. Fatigue parties frequently scoured the local area for fallen logs to be sawn up and split into billets for the insatiable fuel stoves of the cookhouse. They also accompanied the station truck into Army stores in (or near) the Caboolture railway yards, where we used to man-handle 44 gallon drums of fuel on to the truck (along with other stores) and return along Pumicestone Road. This road was rough gravel, with narrow wooden bridges over creeks. Regrettably with additional traffic (and there were US troops at Toorbul Point opposite Bribie Island) the wooden bridges became shaky indeed. So shaky in fact that the truck had to stop at each bridge, so that we could unload those damned 44 gallon drums, roll them by hand over the bridge, and when the truck crossed over, we re-loaded them, by rolling them upwards on planks to stand briefly before the procedure was repeated at the next bridge. (Personal communication, 2009).

|

|

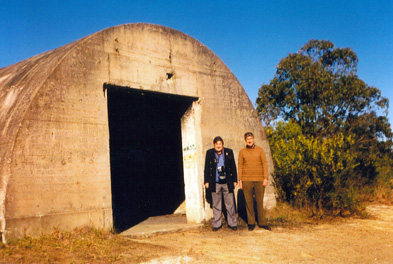

| The two Radar huts in 2009. The level cleared ground was essential for accurate altitude measurements of planes. | Transmission hut (left) and Receiving hut (right). Photos taken by Lionel Gilbert in 1963. |

PURPOSE & PROCEDURES

By means of Radio Direction Finding the Unit's responsibility was to locate and

promulgate advice of enemy and other aircraft approaching to locality of the

station. At its establishment it had a total of 30 personnel consisting of one

RAAF Officer, Senior Operators, Operators, Guards, a General Hand, a Clerk, a

Cook and Assistant and several Radar Mechanics. The Operators communicated

plotted data to the 8 Fighter Sector (8FS) in Brisbane by land line (with coded

call-names) or radio telephone using Morse code. The Radar Operator monitored

aircraft activity from an eleven inch cathode ray tube screen. Using the goniometer consisting of switches and controls of the direction and height

finding components, the operator would alter the screen and make comparisons to

decipher the direction, elevation and distance of the aircraft. The radar

mechanics were required to regularly climb the radar towers to service relay

switches and aerials. The ACO, a fixed radar station, had some advantages over

others with its quick height finding capabilities and ability to monitor

aircraft movements up to 200 miles. The bearing and distance of each aircraft

was called out by the operator; a recorder noted the exact time, distance and

bearing as called out while another marked it on a large map of the area

“covered”. The “plots” (i.e. bearing and distance) were immediately relayed to

the 8 Fighter Sector in Brisbane. The Fighter Operations Room was

located in the WD & HO Wills Building in Brisbane where 'Ops Room' attendants

would take the calls from the various Radar Stations around SE Queensland and

place aircraft and shipping symbols on a plotting table. The average daily

number of aircraft plots at Toorbul 210 Radar Station was 433 for the busy month

of September 1944 with one heavy day reaching 540 plots. Thus a typical

operating crew would consist of one person on the receiver watching the

base-screen of a cathode ray oscilloscope, seeking signals from reflected radio

waves transmitted from the nearby transmitter igloo and its tower; another

beside him with a clip board to record and call out the bearing and distance of each aircraft; a third to relay

information by speech contact to the 'filter room' at Fighter Sector HQ in Brisbane; and a fourth to record bearings

in grease pencil and distances on a large Perspex map board, producing a tracing of the route of

an aircraft. Half an hour at a time was considered the appropriate unit of

activity for the operator and so the roles were rotated about every half hour.

Note: All Fighter Sectors were reclassified to Fighter Control Units on 7 March

1944 and then renumbered by adding 100 to the original unit number (eg 8FS in

Brisbane became 108FCU).

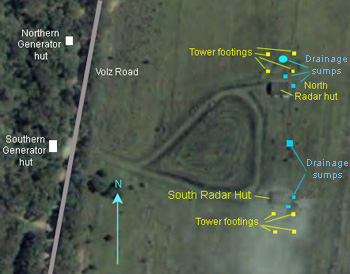

PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION

The station was designed by the British Directorate of Works for the Air

Ministry, Britain and was constructed by the Australian Allied Works Council in

1942 - 1943. The Radar Station 210 site is located on private (Bishop's)

property off Volz Road, Toorbul. The station consisted of six main structures:

Two Radar control huts (igloos): the northern Radar Receiving

(Rx) hut; and the southern Radar Transmitting (Tx) hut;

Two Electricity Generating huts (igloos), a northern and a

southern hut - one for each of the radar stations;

Two 42 metre (135 ft) high wooden towers, one for transmitting and one

for receiving.

Plus the campsite, consisting of the mess, the administration office, stores

hut, officers/sergeants and medical orderly quarters, bunk hut, ablution and

showers block, and guards' tents. A 2000 gallon tank was erected next to the

Parry-Okeden's house (Ningi), about 190 metres south of the campsite. The

tank received it's water from Ningi's roof and was fed through a galvanised

waterpipe to the kitchen in the camp. All that remains of the tankstand are the

support brackets

Layout of the campsite on the western side of Volz Rd. By 1943 the CCC tents were gone.

|

|

| The physical layout shown on a Google Earth map. 27°04'32"S, 153°08'33"S |

A female wallaby with joey were on Volz Road to greet me. |

|

|

|

|

Tank stand brackets |

Cow's skull near the tank stand |

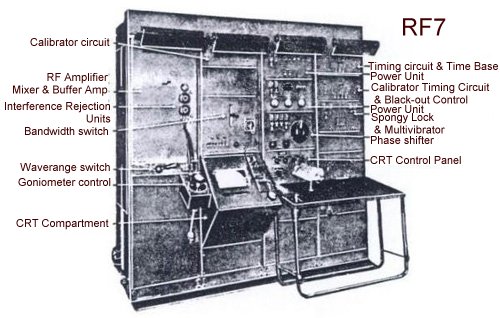

TECHNICAL DETAILS

The ACO radar used a floodlighting type wave system capable of simultaneously

scanning a wide area to detect enemy approaches. The sophisticated electronics

were the second generation of British CH type of radar, operating in the HF

band. The electronics contained panels and features not otherwise seen in other

types or deemed to be necessary in the Pacific during the war. Radar

Station 210 at Toorbul was one of nine ACO radar installations on mainland

Australia. The War Cabinet had originally intended to have 32 units to implement

the plan for Australia's radar station chain, but this became difficult to

achieve and later unnecessary as the war had moved away from Australia and the

need was for air transportable stations. The ACO radar equipment sent to Australia was originally intended

for other territories such as Malaya and Singapore but diverted after Japanese

invasion of these countries. Radar Station 210 was sited on flat cleared

farmland adjacent to a eucalypt and swampy melaleuca forest. The transmitter and

receiver towers were over 42 metres in height and spaced 100 metres apart to

ensure that radio pulses were received as echoes and not confused with

transmissions. The floodlight system of the ACO radars required a high volume of

electrical power sourced from power mains with backup generator located in a

smaller dedicated bunker. Bombproof bunkers, meant to be underground, housed the

electronics for transmitter and receiver, each console weighing two tons.

The transmitter was a British MB3 model which put out 250

kW of

power at 42.5 MHz. The large output meant the valve filaments were drawing huge

currents (37 - 38 A or so) necessitating the big generators and heavy

underground cabling. The frequency was in the VHF band which would later become a

common use in television transmission. However, in 1942 this short wavelength

was unfamiliar technology. The transmitter aerial system was in two parts set at

different heights to enable height finding using the floodlit system. Each part

had four elements to cover four sectors of 120 degrees. The receiver was a

British RF7 (receiver fixed location) model built in four vertical racks held in

a frame of 2 x 2 x 0.6 metres. The receiver detected radio echoes from all

directions simultaneously. The receiver compared the strength of the echo from

within a radius to identify the direction from which a signal was originating.

The receiver had two parts on the tower plus crossed dipoles used for the height

finding of an aircraft by comparing the echoes from the higher and lower

sections on the tower. As the towers did not rotate like those commonly used in

other radar models, the ACO radar installation required fourteen switches on the

receiver tower and more on the transmitter . These had to be constantly relayed

from on to off, lower to higher and to between different directions. The

switches were controlled by the radar operator from the radar console located

within the bunker. It is said that the receiver cost £250,000 in 1943 ($14.0

million in 2009 dollars). Many radar mechanics and operators believed that the

smaller LWAW (light-weight air warning) radar systems could give just as good

results. Radar mechanic Keith Weir (78446) - serving with RAAF 41 Wing said the

LWAW sets he used in Kiriwina Island (one of the Trobriand Islands just to the

south of Rabaul in the Solomons Sea) and at Momote Point (Los Negros Island in

the Admiralty's) in 1943-44 was the equal of the ACO sets as used at Toorbul.

Ed. Simmonds was responsible for the technical installation. After the

war Ed became a civil engineer but remained quite aware of the limitations and

successes of the ACO radar system. He said that the electronics contained panels

and features not otherwise seen in other types or deemed to be needed in the

Pacific and because the ACO was totally unsuited to the fluid nature of WWII (as

shown in Malaya) it was not used in the Pacific. However, he said, in a fixed

situation it had some advantages over the existing 200 Mc/s VHF COLs and LW/AWs

namely better penetration of thunderstorms and quick height finding ability.

Fighter Sectors frequently asked operators to exercise extra vigilance during

storms when other search radars could be affected. Ranges in excess of 200 miles

were recorded on high flying aircraft and ACOs fulfilled the secondary role of

support to Allied planes.

|

| The RF7 Receiver as used at Toorbul 210RS |

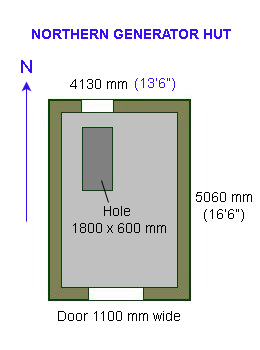

1. GENERATOR HUTS (IGLOOS)

There are two Generator huts and are quite easy to see as they are beside

the road. The axis of the huts is north-south and the buildings are very much

identical. The northern hut seems to have been used for animal feed and the

southern hut has clear evidence of human occupation (mattress, blinds, bong).

Originally, a Lister Diesel Generator was the Prime Mover for the power supply

and there was one of these in each hut.

The concrete igloos are about 15 metres in the bush off Volz Road.

Each is 5060mm (16'6") long and 4130 mm (13'6") wide and 3150 mm

(10'3") high. They have vertical sides for the first 1200 mm with a

cylindrical top.

The steel

reinforced concrete is of a high quality and is 300 mm thick although there is

some evidence of spalling. One end has a glass louvered window measuring 600 x

1000 mm to provide ventilation for the diesel motor. A 1100 mm wide door is

located at the other end and is about 2100 mm high. Inside, there is a trough in

the floor in front of the louvers measuring 600 x 1800 mm . This was the exit

hole for the cables. There are two 100 mm vents in the ceiling. There is also an

exhaust vent above the door and a pipe in the floor for electricity cables. On

the wall are the switchboard mounting holes made from wooden dowel. The

alternators

were coupled to 25 kVA Lister diesels driven and maintained by a Driver Motor Transport (DMT) who was qualified to

handle motors whether they were fixed or mobile. Sgt “Ed” Geier (127819) had

this task. The alternators produced 3 phase power and was connected to the Rx

and Tx igloos via a armoured underground 4-core cable. There was a Lister

25 kVA diesel alternator in each generator hut (used alternately every 6 hours when the

other was being refuelled, serviced or repaired). Each was connected to a switchboard

inside the hut (to switch from one to the other) and cables ran to both the Rx

and TX igloos some 100 m away. One diesel or the other was running 24 hours a

day (in 6 hour shifts). The Listers performed very well; even when they were

badly in need of decarbonising they would start almost first time blowing smoke

rings and emitting showers of sparks.

1A: NORTHERN GENERATOR HUT - provided power to the

igloos 150 m to the east.

|

|

|

Floor Plan |

Timber doorframes have largely rotted away. The wood is said to be turpentine, sourced locally. |

|

|

|

Northern end of the North generator |

Doorway into the north generator hut |

|

|

|

Northern end (inside) of the northern hut |

A 100 mm square vent hole (northern hut) |

|

|

|

| Pipe out of ground for electrical power cables | Arrows show wall plugs for mounting of instruments on the southern wall. | Rusted and bent steel bracket in a wooden wall plug |

1B: SOUTHERN GENERATOR HUT - provided power to the igloos 116 m to the east.

|

|

|

The author at the north end of the southern generator hut |

Chimney vents for diesel fumes (southern hut) |

|

|

| Reinforced concrete is showing some spalling but is of generally high quality | Inside the southern generator hut. The trough has filled with rain water as the louvers are broken. |

|

|

| Author surveys the southern generator hut | Posts outside the hut. Now what was on these? |

2. AERIAL TOWERS

There are two arrangements of four concrete footings that originally

supported 44 metre (144 feet) high timber aerial towers. The concrete footings are arranged in

a 9.0 metre square pattern with remnant steel supports protruding from each block.

The towers were built to the design of the Directorate of Works for the

Air Ministry in Britain by the (Australian) Allied Works Council. The complex timber

towers were prefabricated offsite. The timber merchants Codey and Willis

of Glebe, NSW had the initial contract for the prefabrication and

erection of the timber towers for the ACO stations. The timbers

were cut to specification and marked in the company yard at Lidcombe,

NSW then shipped to various locations on the eastern coast including the

Toorbul station. In some cases the timber had shrunk when the crew

started to erect them and it was necessary to either burn out bolt holes

or re-drill them on site. The timber towers were fixed to steel members set in four

concrete footings and placed in a north and south alignment. The complex

arrangement of the structure was designed to withstand hurricanes and

took a 12-13 men twelve weeks to construct. The crew would all work on

one tower from foundations upwards until the tower reached 60 feet. Then

two carpenters and a rigger would complete it.

The carpenter from the Civil Constructional Corps during the

aerials' erection was Bill Brown, a 'good bloke' as he is remembered.

It is a shame that he

technical integrity and aesthetic characteristics have been lost with

the removal of associated electrical and timber fabric of the aerial

towers. The remains of four square concrete footings, approximately 1.5

m x 1.5 m, of the wooden tower, which carried the receiving aerial, are

located approximately 10 m to the east of the igloo hut. The cost of the

two towers is disputed: Mellor, in The Role of Science and Industry,

quotes that each ACO tower cost £50,000 (page 431). But invoices for

towers from Adelaide suggest that the cost of each tower is likely to be

£5,000 (perhaps a typographical error in Mellor's book). Retired

engineer, former Sgt Ed. Simmonds from the Radar Installation and

Maintenance Unit (1RIMU) who was responsible for the installation of the

equipment believes that Australia was sold a lemon with the equipment as

it was out-of-date by the time it was used here. Nevertheless, he said

that "properly sited, it was useful for altitude measurements".

Only mechanics were supposed (officially) to climb the towers and then

only for maintenance. One of the achievements was to climb the tower and

then stand upright on the one metre square top, 135 feet above the

ground. At Toorbul Point, one mechanic (Alan O'Rourke) was seen standing

on one leg on

the top of the receiver tower for a bet. He recalls that the C/O Price

was not at all amused ("I can still recall the look on his face").

|

|

| Alan O'Rourke in 1942 | Radar Mechanics Robert Burne (left) and Alan O'Rourke revisit RS208 Newcastle in 1973. Each became known as "Herman the German" (Hermie 1 and Hermie 2) for their proclivity for speaking high-school German when at Radar Station 308 at Catherine's Hill, Newcastle. |

|

|

| Receiving tower at Toorbul RS210. Taken in 1944 (from Elizabeth Parry-Okeden). | Both towers at Toorbul. Photo taken in 1944 (from Elizabeth Parry-Okeden). |

2A: RECEIVING TOWER - northern. Type of array: 2 sets of cross dipoles on 132 foot tower.

|

|

| Toorbul Radar Receiving aerial footings are 9 m apart | Close up of Toorbul Radar Receiving aerial footing |

|

|

| Steel supports are 12 mm thick. | Something was fixed to this block (400 x 300 mm). |

2B: TRANSMITTING TOWER - southern. Type of array: 3 stack main array, 2 stack gap filler on 132 foot tower.

|

|

| Toorbul Radar Transmitting aerial. The steel is ½" (12mm) thick. | Transmitting aerial - close up of rusted bolts |

|

|

| The cables came down the centre of the towers into this 1.5 m diameter concrete structure which kept the underground pipes waterproof when it flooded. This one was located under the Receiving aerial. | Looking at the Receiving hut from directly under the Receiving aerial. There is a small square duct (1200 mm sides) between the two. Underground co-axial cables and switch wiring was conveyed to the igloos from here. |

3. RADAR HUTS

An igloo shaped above-ground bunker was located close to each of the

aerial towers. The bunkers were made of concrete and built to British

design for withstanding bomb blasts. The bunker located in the northern

part of the site housed equipment for the receiver radar equipment and

the southern bunker housed the transmitter equipment. This was true of

all ACO stations. Each bunker contains a small passage leading to a

turret at the coastal (Pumicestone Passage) side of the structure. The passage and turret

indicates that these bunkers were intended for underground installation,

however were constructed above ground at Radar Station 210 and at all

Australian ACO Stations it would seem. The siting of the bunkers above

ground demonstrates an Australian adaptation that adds to the historical

importance of the site. In the UK, the igloos were located underground

but in Australia and particularly at Toorbul, the igloos were above

ground. The Toorbul sit is quite low and swampy. After the war, with the

drains blocked and the pumps not being used it was not uncommon to

have 6" of water in the huts. Building them underground was

neither practical nor sensible. The footings and bunkers are symmetrically

placed across an east-west axis. The bunkers have remnants of electrical

fittings and recessed areas on the internal walls and concrete slab

floors and an egress on the eastern walls. were built on

steel-reinforced concrete slab foundations 300 mm thick. On top of the

concrete slab floor a waterproofing layer of hot bitumen was poured and

when hardened another slab of 90 mm was added. Each igloo has a

tower located at one end, which is believed to have been utilised as an

exhaust, with fans drawing in fresh air from the front of the igloo and

sucking it out the tower opening (see photo). The tower extends 1200 mm

above the top of the igloo to make a total height of 5000 mm. The two igloos are 56 m

apart (to centres). Along the rear wall of the igloo is a small timber

framed opening. There is an opening on the southern side, 2400 mm wide,

which was the doorway. It had a hardwood frame but this has been removed

(possibly by white-ants). The door itself is no longer present.

Anecdotal evidence indicates that the door was staggered, that is, enter

one side, walk around one partition, and then another, like an s-bend,

to ensure that light was contained inside the igloo at all times. This

would also have provided a constant flow of air into the igloo, which

was then drawn through the igloo by an exhaust fan situated in the

tower. The floor was covered with heavy rubber which had to be mopped

and polished each day during the one hour maintenance break in both the

Transmitter and Receiver igloos, partly to minimize dust but, as the

operators believed, "mostly to keep us disciplined". Mild steel reinforcing rods of 10 mm

(3/8") diameter and 200 mm (8") long poke out from all over the igloos

(photo below). These were intended for camouflage but the buildings were

never camouflaged. As Lionel Gilbert said "It's hard to camouflage 135

foot towers; they're hardly subtle."

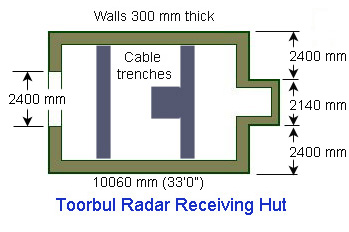

3A: TOORBUL RADAR RECEIVING HUT (NORTHERN) - RX

|

|

| Floor plan - northern radar hut. Exit holes for the aerial cables are shown in the concrete floor. | The author surveys the northern hut. It is 3800 mm high but the doors have been taken or eaten by termites. |

|

|

| The eastern interior wall showing the doorway (minus door) and the yellow air ventilation duct above the doorway. | Walls are 300 mm (12") thick and designed to stand the impact of a 500 lb bomb. |

|

|

| The main exit to the hut as seen from the inside. The doorway is 2400 mm wide by 2400 mm wide. | One of the trenches in the floor to take the electrical cable. |

|

|

| Looking up into the tower. The glass louvers and hatch are no longer extant. | The tower with the dilapidated Kombi van. The top of the tower is 5000 mm from the ground. |

|

|

| Note the shape of the turret. There is a small covered opening 300 mm square on the back. | The turret in the tower has two openings; a glass-louvered section and a small hinged doorway. Note the camouflage supports (which were never used). |

|

|

| The ventilation duct. It is not certain what the small platform is to the right but the blocks of wood have been added recently. | The other side of the ventilation duct, opening out into the tower. |

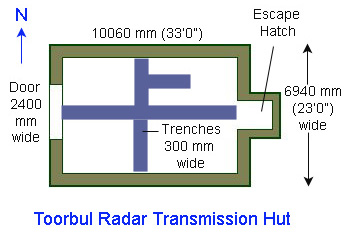

3B: TOORBUL RADAR

TRANSMISSION HUT (SOUTHERN) - TX

|

|

| Floor plan - southern radar hut | Note the flat ground surrounding the huts |

|

|

| Rear (eastern) wall showing the doorway and above-ground exit hatch. There is a 300 mm diameter vent in the ceiling. The landowner has a hay-baling machine and some tractor spares stored here. | The eastern end of the Transmission Hut showing the turret's escape hatch and tower clearly. The tower is 2140 mm wide by 900 mm deep. |

|

|

| Author measures width of tower (2140 mm). At his feet is a well (see photo below right). | The turret showing the escape hatch and camouflage support rods. |

|

|

| The tower is 1500 mm deep. The author took these photos on 23 January 2009. | The 'sump' at the base of the tower is 1000 mm square with 120 mm concrete walls. It was to assist with drainage of the cable trenches and was pumped out periodically to an area well away from the site - "probably only to run back again" as the operators believed. Some wells had hand pumps, other, like this one, had a Tecumseh petrol engine pump (USA). The broken lid is shown here inside the well. |

|

|

| Small window on the southern wall of the Transmission hut. The window is 1800 mm from the eastern end and is 300 mm square.The coaxial 'feeder' cables were attached to the aerial through this opening. | A concrete pillar faces the feeder cable exit hatch, but now it only supports swallows' droppings. |

|

|

| The support pylon is about 10 metres from the edge of the hut. A concrete box structure can be seen to the right. This was for cable entry into the underground pipes. | Photo of the same scene taken by Lionel Gilbert in 1963. Some of the wood is still in place on the aerial supports. |

|

|

| The entry point for cables as mentioned in the photo directly above. It is 1200 mm square with walls 150 mm thick and is only 1 metre from the nearest pylon. | 3/8" mild steel reinforcing rods poke out from all sides of the two radar huts. They were to support the camouflage netting. |

STAFF: (as recalled by Radar

Operator Lionel A. J. Gilbert, 135268) Commanding Officer (1): 20 Sep 1943 FlgOff Athol G. Price

(255060); 2 Mar

1944 PltOff Lionel J. Burder (119945); 15 Mar 1944 FlgOff A. G. L. Price; 4 Apr 1944 PltOff

Maxwell T. Sinclair (51844); 30 Dec 1944 FltLt John C. Sands (61621), 17 May 1945 FltLt Morris W. Gunn

(63095). Medical Orderly (1):

Corporal Percival “Perce” Davies

Fitter DMT (1): Edwin Wilfred “Ed” Geier (127819) -

transport/driver/mechanic/generator attendant Guards (2): Mervyn Roy “Merv” Delphin (126307) and Leslie John “Jack” Kyte

(152782) (who had served in WW1)

General hand (1): Cpl. Frank Purser (with whom I

established a small garden for fresh greens and tomatoes – it was wiped out by

insect invasions!)

Clerk General (1): Wallace “Wally” Coomber (62089) Clerk Stores (1):

Cooks (2) and

Assistant (1): I’ve forgotten them – They used a fuel stove fed with bush wood –

fatigue parties regularly brought dead logs for reduction by man-powered

cross-cut saws.

Radar Mechanics (4): William Brice “Bill” Whipp (71925)

George Peyton Whitfield (81669) Albert Rodney Sing (57526), Alan “Herman” O’Rourke,

Frank Savage (79458) - dropped to 2 by June 1945. Senior Radar Operators (both fresh from Darwin):- Corporal Geoff Felton, Sergeant Gordon Clarke

Radar Operators: Kevin Hawkins (124840), Allan Gray, John Walker,

Jim Mitchell, Don Edwards, Ray Stewart, Colin Wesley Tipping (13117), Lionel Arthur

James Gilbert (135268), Clive James Taylor (49323). Telegraphists (2): Machinery: 1 Light Truck. The General Purpose Utility was

removed on 14 April 1943. The

Radar Installation & Maintenance Unit (1RIMU) included F/O Bill Sanderson

and the celebrated Radar historian Sgt Edwin (Ed.) William Simmonds (61591)

(coauthor, with Norm Smith of Echoes over the Pacific, 1995; Radar

Yarns, 1991 & More Radar Yarns, 1992.

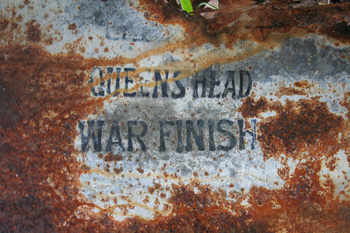

The 24 gauge galvanised sheet

iron was "Queen's Head" brand. The

lettering was always stamped with the same coloured blue dye.

Queen's Head was the most uniform and reliable plain

galvanised sheeting on the market. It had been around since

1887.

Queen;s Head was made by Lysaght,

whose name can still be seen on the piece above. Lysaght was the only manufacturer of galvanised iron and

steel sheet in Australia prior to and during the Second World

War. The symbol K42 on another piece indicates that the

galvanised iron was made at the Port Kembla works in 1942.

This is the only structure left

standing in the camp. It appears to have been one of the storage

boxes at the mess; possibly for firewood. The concrete is

beautifully rendered.It measures 1073 mm W, 980 mm D and 840

mm H. Alan O'Rourke remembers helping the cook's assistant

(a Queenslander) cut firewood with a 6ft bush saw.

The 6" thick concrete floor has been cut

up with a diamond saw to reveal the high quality matrix that

has lasted 70 years.

|

|

| Concrete floor slab is now in a broken heap. | 4" diameter Fibrolite water pipe also remains |

|

| A final photo. The male wallaby stands guard as his female partner and her joey hop off into the bush. Goodbye! |

Richard Walding, Brisbane, Australia.