USCG CABLE SHIP PEQUOT - UNITED STATES

HARBOR DEFENCES

The Pequot's Magnetic Camouflage |

|

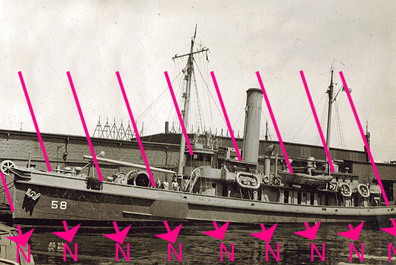

The US Coast Guard Pequot. During WWII this cable ship laid top secret Indicator Loop cables to protect harbors from German U-boats. Her mission ranged from the ports of Virginia up to Argentia, Newfoundland. (Calamaio family). |

HOW MAGNETIC MINES WORK

Before he joined the crew of the Pequot, Radioman John McCormack was jolted out of

his bunk on the USCG Storis (WAGL-38) near

Greenland when the Coast Guard cutter Escanaba (WPG-77) exploded and sank in a matter of minutes

directly in front of Storis. At the time it was assumed Escanaba was the victim of a U-Boat torpedo, but

German records indicate that no U-boat commander ever

claimed victory for the sinking. Speculation has

increased that a magnetic German mine was responsible

for the Escanaba’s icy fate.

The Germans planted several types of surface and

sub-surface sea mines in the shipping lanes commonly

used by the allied convoys and along routes that the Pequot routinely steamed. These mines were

detonated not only by physical contact, but by the use

of magnetic sensors. As a ship passed above it, the

mine's detector sensed a change in the magnetic field

emanating from the steel hull. They were designed to

trigger and explode against the mid-point of a hull,

usually breaking the ship in half and sinking it.

|

115. The first type of German magnetic mine used in the war. Recovered unexploded from Shoeburyness, England on November 23rd, 1939. (British Royal Navy Photo) |

All ships have a permanent magnetic field or “magnetic

signature” which is created during shipbuilding as a

result of the hammering, riveting, and movements of the

hull’s steel plates during construction in the shipyard

while in the presence of the Earth’s magnetic field (see

photo below, left). Changes to the strength of the

magnetic field in the hull also occur at sea mainly due

to the vibrations while in the Earth's magnetic field.

Any steel ship is like a huge floating magnet and the

Germans knew it. In November of 1939 alone more than

200,000 tons of shipping was lost off the coast of

England to German mines. To protect warships and

merchant vessels, the Allies needed a way to render

their ships “magnetically silent” and they needed it

fast.

In Britain Commander Charles

F. Goodeve of the Royal Canadian Navy (later Sir

Charles) worked with the Royal Navy in 1939-40 to

develop ways to neutralize the inherent magnetism of

steel ships. A series of experiments and sea trials was

conducted at the H.M.S. Vernon naval research shore

station. Work at Vernon determined that the magnetism in

a hull can be read by having a ship pass over a loop of

cable on the bottom of a harbor, like a miniature

indicator loop. The research team developed two methods

to trick the German sea mines. Since the Germans used

the term “gauss” as the unit for magnetic strength when

developing the triggers for mines, Goodeve named the

first hull treatment “degaussing” - that is - removing

the "gauss" (magnetism).

|

|

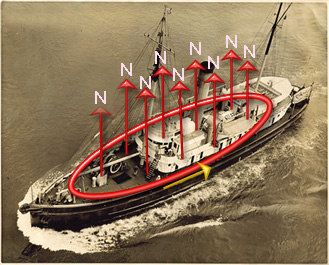

| 116. A ship such as the Pequot built and sailing at northern latitudes similar to Boston would have a "North-down" magnetisation due to the direction of the Earth's magnetic field there. The Pequot would behave like a magnet with the north pole underwater. | 117. To eliminate the Pequot's magnetisation an electric current would be passed through a coil orientated like the one drawn above. The direction of the current is shown by the yellow arrow and this would produce a "North-up" magnetisation to cancel that of the ship's. |

Degaussing involves the permanent installation of large

copper cables around the perimeter of a ship’s hull just above

the water line through which a large continuous electrical

current is passed which creates a magnetic field in opposition

to the field of the ship - and neutralizing it (see above

right). This system was hooked up to the ship’s electrical

system to easily permit degaussing at sea.

Deperming or wiping consisted of having a ship slowly

move past stationary electric coils while in port, or by having

large copper cables pulled across the hull through which a

current of up to 2000 amps DC would be passed, to “wipe or

flash” the ship to eliminate it’s magnetic signature. For most

small ships deperming normally had to be repeated every 3-4

months.

Both of these countermeasures proved to be successful and

permanent degaussing equipment was installed first on the

largest ships in the British and American fleets. Once these

techniques using large copper cables were widely adopted, the

demand for copper in the US, which was already in short supply,

soared, resulting in the minting of steel pennies by the US

Treasury for the remainder of the war.

Research indicates that the Pequot’s home port had the largest

degaussing operation on the Atlantic coast first at the Boston

Navy Yard, and beginning in 1943 at Castle Island in Boston

Harbor. Between 1943 and 1945 more than 500 ships were degaussed

at Castle Island. A note in the Pequot’s file at the US Coast

Guard History Office shows that between May 26th and June 26th

1942 the Pequot was at the Boston Navy Yard for

“conversion and installation of permanent degaussing” equipment,

although none of the photographs of Pequot after 1942 show the

addition of an exterior degaussing coil around her hull common

with permanent systems of the time. So although speculation

remains about that permanent solution, it is safe to assume that Pequot had periodic deperming treatments at the navy yard

or Castle Island to camouflage her magnetic signature and

greatly reduce the threat from sub-surface mines.

CASTLE ISLAND MAGNETIC RANGE

During World War II Castle Island in South Boston was the home of the Navy’s “Boston Magnetic Range,” which was both a deperming station and demagnetizing facility. This is where the Pequot went for periodic deperming treatments. The island also served as Boston’s Port of Embarkation.

|

Castle Island in Boston Harbor during WWII where on the left we see a ship being loaded with cargo and a deperming slip in the foreground at the end of a long pier. |

The Island is home to Fort Independence which has a colorful history being first established by the British in 1634 before the American revolution. The existing granite fort was constructed between 1833 and 1851.

|

A cargo pier with Fort Independence in the background. A demagnetizing range house was constructed on top of the Fort. Cables were laid across the channel and attached to the house where magnetic measurements were read. Ships were directed to continue on if demagnetizing wasn’t necessary, or head for drydock if the readings were too high. |

Castle Island is now one of the most popular parks in the metropolitan Boston area managed by the State of Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation

|

|

(Photos courtesy of the MA Dept. of Conservation and Recreation from the US National Archives and Records Administration and the Boston Public Library)

FEEDBACK

If you have comments or queries specifically

about the Pequot or her Escort Ships, please contact

Chip Calamaio chipaz@cox.net, Phoenix, Arizona,

USA. (H) 602-279-4505.

Click here to go to the Pequot Main Page.

Research and design: Chip Calamaio and Richard Walding