OF THE ROYAL NAVY AT LOCH EWE, SCOTLAND

This is the story of the controlled minefield built during WW2 as part of the Royal Navy's anti-submarine harbour defences of Loch Ewe. Ihe minefield was supplemented by a 'guard loop' on the seaward side of the minefield, and a 'mine loop' surrounding the minefield. Even though it is often said that Loch Ewe was protected by 'indicator loops' but these were just guard and mine loops that worked on the same principle of electromagnetic induction, they were not what we normally call 'indicator loops'.

|

|

If you have any feedback please email me: Dr Richard Walding Research Fellow - School of Science Griffith University Brisbane, Australia Email: waldingr49@yahoo.com.au |

LINKS TO MY RELATED PAGES:

Indicator Loops - an overview (YouTube, 70 minutes)

Loch Ewe is located in the north west Highlands of Scotland about 80 miles west of Inverness. It was of great strategic importance in World War II partly because it is north-facing (and therefore protected from the prevailing westerly winds), plus being less exposed to air attack than the existing base at Scapa Flow. It was adopted as a gathering place for the North Atlantic Convoys destined for Russia. As well as anti-submarine boom nets, anti-submarine guard loops were laid in conjunction with the controlled mines across the mouth of the loch. Anti-aircraft guns were positioned at Aultbea, Firemore and Tournaig, and a coastal defence artillery site established at Rubha nan Sasan beyond Cove.

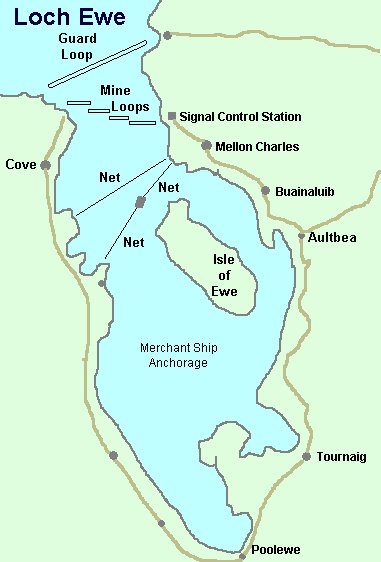

The map below shows the location of the harbour defence control huts, the antisubmarine guard loops, the mine loops and the boom nets used by the Royal Navy for its antisubmarine defences in World War 2. The guard loop for the mines ran from the island of Eilean Furadh Mor in the west to Slaggan Bay in the east. A series of mines were laid nearby and these could be detonated from the control centre at Leacan Donna.

|

Loch Ewe harbour defences |

A 40-page book (£7.99) by Steve Chadwick on "Loch Ewe during World War II" has been

produced by the Gairloch and District Heritage Society. Order a copy through Ullapool Bookshop).

Here's an extract from Steve's book (used with permission): Preface (Page 1)

To drive past Loch Ewe and Gairloch is to pass through scenery of wild and magnificent proportions. The ribbon of road picks its tortuous way through cliffs between sea and mountain, with each view seeming to vie with its predecessor for breathtaking grandeur. But what is this that sits ill with the scenery? Rusting metal posts, crumbling concrete edifices, old gun emplacements. What happened here, and why is it thus? It is with some trepidation that as an amateur historian, I begin to write the World War 2 Loch Ewe story. I began to realise as I researched the area for historical background for my walking guides, that here was history being lost before our eyes. A generation who's memories had to be captured before they were lost for ever. The war saw an almost total black out on pictures and media coverage, and many official records and log books have been lost, so that personal memories are to a large extent all we have to go on. I have spent many hundreds of pleasant hours making notes and talking with local people and war time personnel who have come back to visit. Indeed Loch Ewe must hold a very special place in many people's hearts for they come back year after year, but each year fewer return. Correspondence has come in from all over the world and each piece has helped to fit the jigsaw of a censored history. Some aspects are now fairly well documented, whilst others remain obscured by time and lack of data. I appeal to anyone who has a story or information on the area during World War 11, to let myself or the Gairloch Museum know, and let us record the information before it is lost. If what I say here is wrong or can be added to, let us know! In writing this I have leant heavily on the actual recorded notes of those involved. I make no apology for this, indeed I feel it adds to the authenticity of the writing to quote directly and to use the style of the originator. Finally thanks to all those who have given of their time and precious memories. It has been a pleasure during these last eight years to listen to people tell of their past, and to do what I can to bring to light a most remarkable and unsung part of our history. Steve Chapman - 1996 |

Chapter 1 (Page 2)

On the 7th of September 1939 the Admiralty gave Admiral Forbes a greatly exaggerated estimate of the bomber strength available in northwest Germany for an attack on Scapa Flow, and ordered a temporary base be prepared on the west coast of Scotland. The Commander-in-Chief selected Loch Ewe and sent the HMS Guardian there to lay antisubmarine nets. For security reasons, until March 1940 Loch Ewe was designated Port A. Between the 9th and 15th September the Fleet flagship and other major units arrived at Port A, they included HM ships Nelson, Rodney, Repulse, Ark Royal and Hood. They were visited by the First Sea Lord and returned to Scapa on 21st September, and prolonged discussions on the future of the Fleet's bases began. On instructions from the Admiralty, Admiral Forbes returned to Loch Ewe on 1st October with the Nelson, Rodney, Hood, Repulse, Ark Royal, and the 6th and 8th Destroyer Flotillas, leaving the Renown and Royal Oak at Scapa Flow. Although, owing to its geographical position, Loch Ewe was less exposed to air attack than Scapa Flow, it was even more unprotected against submarines, for it had only indicator nets and no gate, and was without any shore defences. When they moved to Loch Ewe, the Royal Oak was left behind at Scapa and insecurity against submarine attack was immediately made apparent. There was now no disguising the danger in which the fleet lay, in its temporary base in Loch Ewe. The Admiralty even considered that it was greater than at Scapa, and agreed to give Loch Ewe priority for certain additional anti-submarine defences. It was certain that before long the Germans would discover that the Home Fleet was using the place as a base. Nevertheless, it was decided that the fleet should remain there for the time being, and Loch Ewe was given priority over Scapa Flow for the provision of guard loops and controlled mines. The Admiralty was still apprehensive and proposed that the main fleet base should be moved to the Clyde. Admiral Forbes totally disagreed, on the grounds that a whole day would be required to get the fleet into the northern part of the North Sea. He expressed a preference for Rosyth, where the anti-submarine defences were good, and although it was more exposed to air attack, this was offset by better air defences. It was eventually decided that the fleet should remain at sea as much as possible and return alternately to Loch Ewe and the Clyde until the improvements to Scapa had been completed. At a meeting at the Admiralty on 24th October, the whole question of fleet bases was rediscussed, and it was decided that the Clyde should be used as the main base for the fleet and that Loch Ewe should be abandoned. This decision was signalled to the Commander-in-Chief but Admiral Forbes was still unable to agree. The outcome of a further meeting on the 31st October was finally that Scapa How should be the Home Fleet's permanent base, and Loch Ewe would be retained for occasional use. The temporary base for the Fleet at Loch Ewe was by no means ideal for at 07:52 hrs on 4th December as HMS Nelson was entering the Loch she exploded a magnetic mine. The next phase of Loch Ewe Naval activity centred around its use as a refuelling base for escorts, thereby enabling a new convoy cycle to be introduced from January 1941. Loch Ewe was established as a subsidiary assembly port for convoys, and in view of its growing importance, the naval base was commissioned as HMS Helicon at Aultbea on 14th June 1941. In addition to coastal and Atlantic shipping, convoys for Russia also used Loch Ewe from February 1942. All returned to Loch Ewe, with parts of the later convoys being despatched for the Clyde. |

I had an interesting note [20 January 2016] from Dusty Miller ex Royal Navy Telegraphist, who has lived in New Zealand since 1959. In response to the appeal for any information about Loch Ewe he wrote about Aultbea:

I was serving onboard a Boom Defence Vessel, HMS Barcarole, 12 August 1955 to 23 October 1955. We sailed from Rosyth to Aultbea and did some exercises with submarine nets across the harbour entrance. I was the sole Telegraphist on board and did not take part in these particular operations. Barcarole was a coalburner and we "Coaled up" at Ullapool and the skipper decided we had earned a weekend in Stornaway which was educational to say the least. I remember the small shop which also served as the Post Office and the old lady refused to give me the ship's mail until the skipper confirmed I was legit. The locals in the hotel spoke English until we arrived then they switched to Gaelic and except for the barman, nobody spoke to us, I don't think they liked us for some reason. On return to Rosyth we struck a force 8 gale in the Minches which was one hell of a ride in such a small vessel but we made it. Not sure if this is any use to you.

HMS Barcarole |

Major Cyrus Hunter Regnart (aka "Roy" Regnart) of the Royal Marines.

My thanks to historian Harry Ferguson for the following story about the WWI commander of the naval station at Loch Ewe.

The commander of the station from July 1914 until the end of the First World War was Major Cyrus Hunter "Roy" Regnart. His presence there on such a remote base has long been a bit of a mystery.

Regnart was born on 26 November 1878 and enlisted in the Royal Marines in 1897. He qualified as a Russian interpreter. In 1904 he was promoted to Captain and joined the Naval Intelligence Department (NID) where he eventually became personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence. In December 1909 he left the NID and joined the foreign section of the Secret Service Bureau (SSB), the body that today is better known as MI6, the UK's Secret Intelligence Service. The foreign section of the SSB had only begun operations on 7 October 1909 and consisted of just one officer: Commander Mansfield Smith-Cumming RN. Cumming was struggling: he had little previous experience of intelligence work and he was being outshone by the only other member of the SSB, Captain Vernon Kell of the Army, who was responsible for the home section of the SSB. (This organisation later became MI5.) Kell was making the Navy look bad and something had to be done. Regnart was the answer.

Regnart, described by one Director of Military Operations as "an artist in secret service work", transformed the work of MI6. He established many of the techniques that are still in use today. In July 1913 he was stationed in Brussels in charge of the very first MI6 overseas station (under cover of an upholstery workshop - his father was a director of the Maples furniture company). However, with the outbreak of war imminent, he was withdrawn from that city and re-joined the Marines with effect from 31 July 1914. He was then assigned as commander of the naval station at Loch Ewe where he remained for the rest of the war. His presence there on such a remote base has long been a bit of a mystery. However, two possible reasons have been suggested:

1) that the station was involved in the development of controlled mining loops, the first successful deployment being at Scapa Flow in 1918.

2) that the station was a listening post from where the Swedish overseas telegraph cables could be intercepted and the encoded messages relayed to Room 40, the code-breaking section of the NID. The Swedish cable was being used by the German government to send messages to its embassies abroad as their own telegraphic cables had been cut by the British at the start of the war. Even so, this seems a poor use for an officer of Regnart's talents. He was not a popular officer in the Marines and that may also have been a factor: a later Director of Naval Intelligence said that Regnart was "... neither hardworking, clever nor tactful....", a judgement with which Cumming, who knew him far better, profoundly disagreed.