THE AUSTRALIAN 23 HEAVY ANTI-AIRCRAFT BATTERY - PORT MORESBY WWII

432 TROOP - TUAGUBA "ACK ACK" HILL

This webpage is about the Royal Australian Artillery 23 Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery stationed at Tuaguba Hill in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea. To most soldiers there it was known as "Ack Ack Hill". To the men from the Troop 432 stationed there it became their home for a year. Much of the first-hand account that follows is courtesy of 23 Heavy A/A Battery gunner Laurie Ward.

|

If you have any feedback please email me: Dr Richard Walding Research Fellow - School of Science Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia Email: waldingr49@yahoo.com.au |

LINKS TO SOME OF MY RELATED PAGES:

Guns of Paga Hill, Port Moresby Port Moresby Naval Station

INTRODUCTION

Port Moresby lies on the southeast shore of Papua New Guinea and is built around Fairfax Harbour, the island's largest harbour. As the city capital and administrative centre of PNG, it has the greatest population density in the country. During World War 2 Port Moresby was coveted by both sides for control of the Coral Sea and the South Pacific Ocean. The Allies turned back the Japanese naval forces destined for Port Moresby in the 1942 Battle of the Coral Sea. The area became a major American and Australian staging area and airfield complex in support of the Allied push to the north of New Guinea. Japan suffered a further blow in 1943 when they were routed on the Owen Stanley Range. Harbour defences consisted of several army batteries and a naval anti-submarine indicator loop installation. This webpage is mostly concerned with the Anti-aircraft battery set up on Tuaguba Hill at Port Moresby for the purpose of repelling the attacks by Japanese bombers and fighters from Lae and Rabaul which were intent on destroying aircraft, fuel and munitions at the 7-mile airfield, ships in Port Moresby Harbour, and the guns and searchlights around Port Moresby.

LOCATION

|

The peak of Tuaguba (Ack-Ack) Hill is shown by the red dot. This was also the location of the 23 Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery manned by Troop 432. |

THE ACK ACK BATTERY

[from information supplied by members of 23 Heavy A/A Battery; courtesy of Laurie Ward].

The 23 Heavy Anti-aircraft Battery was formed from the 4th, 10th and 11th batteries in Victoria, Australia, and was assembled at Royal Park, Melbourne, in mid-December 1941. Other personnel were drawn from various coastal batteries. The unit was issued with khaki tropical clothing, including a tropical dress uniform. They all trained on the old Vickers 3-inch anti-aircraft guns.

The unit travelled by rail to Sydney to form 432 Troop and 433 Troop. They were joined by 438 Troop which had been formed from men mostly of the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales. The unit departed Sydney aboard the Aquitania on Christmas Day 1941 and arrived in Port Moresby at 3 pm on 3 January 1942.

A good description of the entrance comes from Bill Morphett who recalled sailing into Port Moresby Harbour aboard the Aquitania on 3rd January with 4500 troops of 30 Infantry Brigade AIF (mostly 39, 49 and 53 Battalions) including the 23 Heavy A/A Battery. They were a part of a convoy that also included two merchant ships, and the escort ships HMAS Perth, Canberra, Australia and Achilles. Bill wrote:

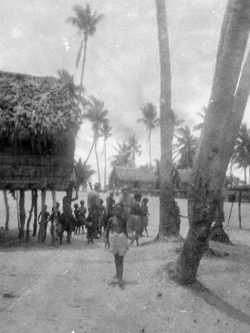

The most prominent land marks were the Owen Stanley Ranges in the distance with peaks above the clouds, green hills up to 900 feet, flanking the Harbour, and the Hanuabada native village. |

The three sections of 23 Battery comprised 208 men, including 8 officers. They disembarked at 7.30 pm to be taken ashore to the wharf area aboard the corvette HMAS Swan. The men were dispersed with the help of three guides supplied by Paga Heavy Battery:

433 Troop - marched (or struggled) the seven miles to Bomana carrying all their gear. Here at the airfield they set up four 3-inch AA guns but as they had no vehicle heavy enough to move these guns, they manhandled them with the aid of an old ute. This Troop moved several times before finding an ideal location, still at 7-mile. Their codename was "Harry 3".

438 Troop - walked from the wharf area to Hanuabada Village just to the north of Port Moresby township - where they set up camp. This was at the back of 'Wards Strip'. Here they established an anti-aircraft emplacement with four 3.7-inch ack ack guns. Please refer to my Hanuabada A/A Battery webpage for more details. Their codename was "Harry 2". All troops in those days were kept busy on roadworks or other menial tasks. The American docks were later built nearby.

432 Troop - walked from the wharf area up the nearby Tuaguba Hill where they pitched tents in small clearings just below the peak. Later, they levelled the top and and installed four 3.7-inch guns, with concrete footings to hold the guns firm. They soon called it "Ack Ack Hill" - the subject of this webpage. Their codename - "Harry 1". Apart from personnel being moved around a bit and experienced men sent to new gun sites for brief periods, 432 Troop remained on the hill until it returned to Victoria in 1944.

|

Some gunners from the 23 Heavy Anti Aircraft Battery, possibly Troop 432. On the right is Clarence Bowden who was with the 23rd after landing at Port Moresby on 3 Jan 1942, but not assigned to troop 432 until 9 March 1944. See more of Clarrie's photos later. |

It is understood that a fourth Troop of 23 Heavy A/A Bty arrived later and set up at Nine Mile ("Harry 4") near the quarry.

These four troops made up the 23rd battery. All were equipped with 3.7-inch guns, two heavy Lewis machine gun posts and one Bofors light anti-aircraft gun. There were four 3.7-inch guns per site.

For more on the role of the 53 Battalion at Port Moresby see 53 Battalion webpage.

GUN EMPLACEMENT LAYOUT

Information about the layout and operation of the gun emplacement on Ack Ack Hill comes from Laurie Ward - a gunner who served there with the Australian Army in 1943 and 1944. His comments here are taken from personal communications in April 2014. By way of background: Laurie was a farm labourer born in Gosford NSW in 1922 and enlisted in the army in October 1941. He arrived for duty at the Sydney Showgrounds on 1 January 1942 and travelled to Dubbo NSW for basic training. Laurie was sent to Newcastle NSW for gunnery training and duty using the Vickers 3" - and later 3.7" - anti-aircraft guns. He was sent north and departed Townsville on 17 February 1943 arriving at Port Moresby three days later. He was placed with 23 A/A Battery (438 Troop) at Hanabadua (near the United States wharf) but was often sent for A/A Bty for duty with 432 Troop at Tuaguba Hill - already known as "Ack Ack Hill".

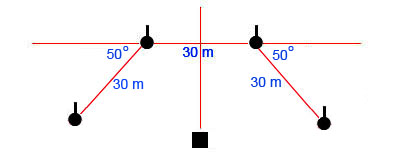

The gun emplacement on Ack Ack Hill consisted of four 3.7" Anti-Aircraft guns arranged in a semi-circular shape with about 30 yards between guns, and 30 years from each gun to a central command post (see diagram below). The men of 432 Troop were assisted in October and November 1942 with construction of the battery defences (air-raid and latrine trenches mostly) by soldiers of the 55th Battalion AIF under the command of Lt Col David Lovell. These same men later complained that when they saw action at Sanananda in December 1942 that they had never fired a machine gun before but that they were good at digging trenches and unloading ships - for that was all their 'intensive training' involved.

Getting the guns up the hill was not easy - as Laurie Ward was told by one of the men who set them up:

When the guns arrived they were to be installed on top of the hill. There was a narrow road that zig-zagged up the hill, a rough track really. The guns were hauled by a 'gun tractor' a special machine for the job. The crew were a combination of army blokes and local people, natives mostly. The hairpin bends on the track proved impossible for the tractor, so a large team of men were set to widening the bends so the tractor could turn properly. |

Laurie said: "Each gun was surrounded by a ring of 44-gallon drums filled with gravel and stacked two-high. A small gap, about 5 foot wide, allowed entry and exit to the emplacement. In the centre of the semi-circle was the command post. It had a rangefinder, and a predictor for fire control - connected to each gun by electrical wires. [Personal communication: 5 April 2014].

|

|

| Royal Artillery 3.7-inch Anti-aircraft battery at Cornwall on the English Coast. Square emplacements were used after 1944. (English Heritage (NMR) RAF Photography 106G/UK/865 6465-7) | Approximate layout of the four guns and command post on Ack Ack Hill, Port Moresby. Exact location to be confirmed. |

|

| The typical arrangement for a four-gun Vickers 3" or 3.7" Anti-aircraft gun emplacement. The angles and distance could be changed to suit the terrain. Laurie Ward said that he thought the guns at Ack-Ack Hill, Port Moresby, were closer because of the limited area for the layout. |

|

| Men of the 432 Troop 32nd Australian Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery on Ack Ack Hill with one of their 3.7" guns - July 1942. Only three guns were calibrated before the first major Japanese air raid against Port Moresby in mid-February 1942. The battery was manned full time, in case of aerial attack. Laurie Ward said that the gunners could fill any position so if one was away with dysentery someone would step in. He moved between Ack Ack Hill and the other emplacement at Hanuabada on regular intervals. Amongst the men in the photo is L/Bmr Walter Bishop - whose story appears later. AWM025948 |

Laurie again: "The electrical wires had a rubber covering and ran off a battery. It was low voltage; it wouldn't kill you. A man stood to operatate the rangefinder and that would give height and range. The rangefinder was a big diameter pipe - about 150 mm (6 inches) - in diameter and about 6 to 8 foot long. They would feed height and range, temperature and wind data into a machine called a predictor. It was a box about 2'6" x 2'6" and sat on a concrete slab. It was about 1200 [4 ft] high. Signals would be sent along the wires to a 'magslip' that adjusted the card on the gun for aiming."

Another feature of the gun was an automatic fuze setter; instead of setting each shell's time fuze (which determined the altitude at which the shell would explode) by hand, the round was dropped on to a tray, where an operating flap (called a "pig's ear" due to its shape) was depressed, where after the fuze setter slid over the nose of the shell, set the fuze, then retracted allowing the tray to move the round into place where an automatic rammer put the gun in the breech, which closed automatically.

|

Hanuabada Battery, Port Moresby, Papua. c. 1942. Men of 438 Troop of the 32nd Australian Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery in their anti-aircraft position at Hanuabada. Note the range finder in the background, and a predicator for fire control in the foreground. The predictor was statically installed in the centre of the emplacement and attached with bolts to a concrete base. Also note the enclosing revetment made from empty drums filled with coral rubble. This setup was used at all 3.7" A/A emplacements including Tuaguba Hill. (Donor M. Williams). AWM P02497.056 |

Laurie: "The Coastwatchers would alert us by radio that Japanese bombers were coming. They would say x bombers or fighters leaving at so-and-so time, expected destination Port Moresby - or Milne Bay or wherever they were going to. They were very accurate. In the early days the Japs wouldn't bomb the airfield as there were no planes there. They'd go for the ammunition stores, ships and so on. Later they went for the sircraft on the ground. Once the Kitthawks arrived that was the first start of the turn of the tide."

"We'd have a watcher with binoculars waiting for the sound and sight of the Japanese planes. We'd all be at action stations waiting for them. The 'level bombers' would usually come down from Lae and drop their bombs on fuel dumps and ammo dumps and then on any aircraft on the field. They would then go out over the ocean and turn back towards Port Moresby where they'd drop any left-over bombs on the anti-aircraft guns. Sometimes they made a special raid to just get the ack ack guns."

Outside the emplacement were several gun pits: one for the Bofors gun - a medium anti-aircraft gun - and one or two for the Lewis Machine Guns. These lighter guns were for shooting at low flying aircraft rather than bombers - a situation where the big 3.7" guns could not move quickly enough."

"Men wore boots all the time. They were standard issue, big, with hob nails to help walk in the mud. The ground was very rocky so you absolutely needed boots, except when you sleep".

"The food was okay; not reasonable, but edible. The cooks did what they could. I can't remember what we had for breakfast but for dinner we had 'M& V' - meat and veges. Potatoes - bags and bags of potatoes but no other vegetables that I remember. For a change we sometimes it was canned potatoes. As far as fruit went - we had none; not supplied anyway. We'd get pawpaws locally from the bush. We drank lots of tea. I think there was coffee for the coffee drinkers. Afte a big action the cooks would have gallons of tea waiting for us. It was just what we needed. I remember the milk: it was powdered milk and it floated in big lumps on the surface of the tea. It was disgusting [laughs]. We decided to do away with the milk powder and have it black."

"Cameras were not allowed but I was surprised to see photos appear at a reunion after the war. Someone had a Box Brownie there during the war. It wasn't me. I didn't keep a diary either. I'm not a diary writer but some were. You weren't supposed to in case the Japs over-ran the post and found all of your stuff."

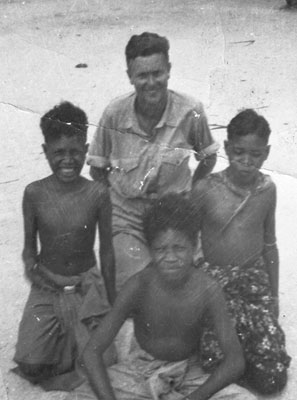

"We were not allowed to fraternise with the locals. You were allowed to say "hello" to them as you went past their villages but you were not allowed to enter them. At Hanuabada you couldn't get in to their village anyway as it was out in the water on stumps and the walkways had been removed at the start of the war. I surmise that it was to keep the Japs from getting to their village if they ever arrived. The natives would use canoes to get from their huts to the mainland. You ceratinly couldn't speak to native women; they were very heavily guarded by men with spears. Sometimes in the markets you could talk to the native men and women. I saw some photos of soldiers sitting with them and that seems to have been okay."

Edwin Holmes' Helmet

Pictured below is the helmet worn by NX96353 Corporal Edwin Dudley Holmes attached to HQ 32 HVY AA BTY Port Moresby. Ian Curry recently acquired this helmet via an online auction in Auckland, New Zealand. He managed to find the Service Number of Cpl Holmes on the inside rim of the helmet. If you have further information about Cpl Holmes please share it.

|

|

| The helmet is a nice near complete early production Australian Mk II model with a British made Mk I liner and strap lugs. | The helmet is stamped CS 13083 and the liner is marked size 7 BH & G (Barrow Hepburn & Gale - London, England) - 1939. The strap lugs are stamped 1939 also. |

|

| You can read Corporal Edwin Dudley Holmes' Service Number NX96353. It's also likely this helmet may have been supplied to New Zealand complete in the early war period before Australia then began the supply of helmet shells and Dunlop liners that were then locally assembled in NZ once local industry started producing parts. |

WALTER BISHOP'S WAR

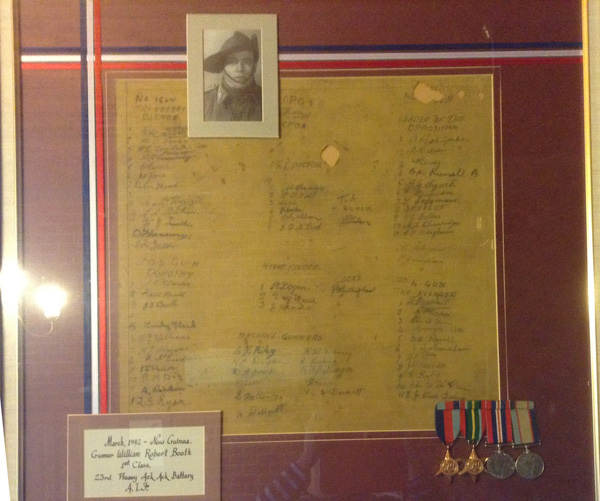

One of the names on the handkerchief (above) under No. 4 Gun "The Avenger" is Walter Thomas Roy Bishop, VX129256 (ninth down). How he came to be at Port Moresby is told below.

|

Wal Bishop outside his parents' home in Merlynston, suburban Melbourne in 1940. |

Walter Bishop was another of the gunners of the 23 Heavy AA battalion that arrived in Port Moresby aboard the Aquatania on 3 February 1942. At the time of his enlistment in August 1940 Walter worked at Millers Ropeworks in Brunswick, Victoria. He enlisted in the CMF (V20992) at Coburg Melbourne and trained at Ocean Grove, Port Lonsdale and Queenscliff in Victoria. His younger sister Joyce recently said "Come the war, and Wal ended up in the army, which he definitely did not want. He joined up in the R.A.A.F. and they told him to wait till they called him up, but meantime the army conscripted him".

Walter's wife Hazel recollected in 2001:

Wal was sent down to Geelong, Victoria in the Engineers Battalion, building makeshift bridges, then posted to Yallourn [Victoria]. After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour Wal was sent to Camp Pell, Victoria - the large army camp at Royal Park near the Melbourne Zoo. During Xmas 1941 he was on leave till midnight and all the family walked up to the Merlynston train station where he caught the train back to camp. We didn't know when we would see him again. A couple of weeks later I got a letter to say they were taken by troop train to Sydney and onto a ship, still not knowing where they were going in case of sabotage. |

Walter sailed from Sydney aboard the troopship Aquatania on 27 December 1941 and arrived in Port Moresby on 3 January 1942. He was assigned to the role of a gunner with the 32 Heavy Anti-aircraft Battalion. Wal's section - 432 Troop - was put on a heavy anti aircraft gun which his wife later said: "they had to put together, and had never seen one before". In July that year Wal was classified as Assistant Height Taker TG II and in August was appointed Lance Bombadier. During an aerial bombing the Height Taker has to keep the enemy aircraft in the crosshairs of his range-finder so that height information can be relayed to the Predictors for setting the elevations of the guns.

Wal's younger sister Joyce said he was always a practical joker and his stay at Port Moresby didn't diminish this. She said that he and another gunner - Mick Dunn, [Michael John Dunn, VX142403] also from Coburg - "took a generator from a field telephone and strung a wire along the seat of the latrine, waited till someone went in, then they would give the generator a crank, with the result that the poor bloke on the dunny would get a mild electric shock".

While he was in Port Moresby, Wal was known to entertain the little native kids by drawing Donald Duck on their arms in white chalk. Joyce said:

They were as black as the ace of spades, and the white chalk would really show up, so the kids loved it. Wal was a pretty good at drawing; maybe that was why he was doing a course of hand engraving at Melbourne Tech. before the war. |

It was a hard life in Port Moresby during the war. Wal suffered tonsilitis, malaria, tropical ulcers on his legs, and had a bad back from being flung back on sandbags during bombings. With continuing proficiency he was promoted A1 Bombadier in early 1944. In April that year Wal left Port Moresby aboard SS Taroona for Townsville and then sent up to Cairns, North Queensland. His wife said

Out of the blue we got word that Wal was back in Australia and he was coming down to Melbourne on leave. It took quite a few days to travel down by troop train. I got three weeks leave from the AWAS [Australian Women's Army Service] and rushed plans for our marriage. After a honeymoon at Olinda in the Dandenongs, we both went back to camp, with Wal not knowing where he would be sent. He was sent to Strathpine army camp just outside Brisbane and then to Newcastle in November. After a few months Wal was sent back to a camp between Newcastle and Raymond Terrace, Tamago NSW. I got discharged and moved there - it was great - Wal got home every night, at times without leave. After about 6 months Wal was posted to Tamworth, and I moved back to Melbourne. Wal was then sent to Sydney and had to work on the wharves. It was 1945 war ended and Wal saw the POWs being brought off the ships so weak and thin and being brought off on stretchers - bloody Japs. |

He was discharged in November 1945. Walter Bishop's employment after the war years included as a painter and decorator, swimming pool manager and motel manager. He died aged 63 in 1983. His wife - Hazel Maude Bishop, nee Ludlow - died in 2001. Information courtesy of his daughter Pam Pendlebury.

CLARENCE BOWDEN'S PHOTO ALBUM

Clarence "Clarrie" Bowden landed at Port Moresby with the 23 Heavy Battery on 3 Jan 1942. He was assigned to the Ack-ack 432 Troop on 9 March 1944. These are photos from his album supplied by his daughter Bev Wilson from Victoria.

|

|

| Bathroom. | Huts in the bush. |

|

|

| Hut. | Clarrie is on the left. |

|

|

| Clarrie on motorbike. | Clarrie and friends. |

|

| Clarrie is second from the right. |

|

|

|

| Clarrie with a local boy and some big fish. | Huts by the shore. | Local huts and outrigger canoe. |

|

|

| On truck. | Bridge-building at the river. |

|

|

| Locals and soldier in canoe. | Locals and soldiers on canoe. |

|

|

|

| Local in canoe. | Bridge building. | Clarrie on right. |

|

|

| River bank. | River. |

|

|

|

| By shore. | Village huts. | Children near shore. |

|

| Army truck. |

|

|

| Soldiers on motrobike. | Soldier on motrobike. |

|

|

| Bathing. | More bathing. |

BERNARD DOOLEY'S WAR

|

Gnr Bernard Dooley 1940 |

Bernard Ortner Doolan served at Tuaguba Hill for 30 months as a gunner on the ack-ack guns. My thanks to Laura Thistlethwaite who provided the information and photos about her Great Grandfather Bernard Ortner Dooley. Laura is a Year 9 student from Geelong, Victoria, who wrote a story about her Pop's experiences for "The Spirit of Anzac" Competition. She wrote: "I have realised that over the years I have learnt a lot about my great grandfather's war experience, and have recently learnt a lot more by looking through many photos and documents of his experiences. This information was a fantastic resource when writing and developing ideas for my story."

Bernard Dooley wrote his reminisinces on Anzac Day 2000 from his home in Victoria.

On 22 September 1940 - my 21st birthday - I went into the army for 90 days training. I was working for a firm called Teisons and was boarding in Packington Street [Melbourne]. Had to pack up and be in camp at Maribyrnong by early afternoon. At the end of training I joined Citizens Military Force in the 4th Anti-aircraft Battery 3" mobile guns and we were stationed at Braybrook, North Essendon (Williamstown Rifle Range at the Williamstown Race Course) on 3.7" (anti-aircraft) guns. Then took over 3.7" static site at Goode Island. |

|

|

Members of the 4th A/A battery in Maribyrnong before they were sent to PNG circa 1940. Gnr Dooley is on the far left. |

Gnr Dooley - back left. |

It was after a time at Goode that we were advised we could be sent to Port Moresby. This was unusual as Citizens Military Forces had never been sent out of Australia. But with troops away overseas we were given the job. So ended up at Royal Park. No final leave so no time to say goodbye. Had Christmas Dinner on Christmas Eve at Royal Park. Christmas Day - no way of making Lethbridge or Hopetown so spent day sitting on seat outside church in Swanston Street. As yet, not knowing what was going on until Boxing Day. All out - breakfast, 5am. Full pack - marched out past Zoo to station and boarded train to city. Left at 8am for Sydney arriving on 27th on ship Aquatania 44000 tons. Convoy consisted of a number of ships - some for Moresby and Rabaul. Escort Destroyer Arunta. |

|

|

Gnr Dooley's tent at Tuaguba, 1942. He is on the far left. |

Next to their tent - 1940. Gnr Dooley is in the centre. |

After first air raid on 3rd February 1942 at 3.55 am it was decided to shift camp to top of Tuaguba Hill. It took too long to reach the top when the sirens went. Three guns were ready by 16th February. Air Force had used the hill for bombing practice and said it was hard to hit top with open sea on one side and harbour on the other; wind and air currents over the top. This proved to be true as time went on. Guns were (1) Strawberry Blonde, (2) Dorothea, (3) The Avenger, (4) The Leader of the Opposition. I was on No. 1 and the site known as Harry 1. For safety, 44 gallon drums filled with dirt were placed around each gun, two on bottom, one on top and sand bags on top of them. Most of this was completed by 16 February 1942 which was our first time in action. |

|

This a photo of the 4th A/A battery Football Team c. 1941. This was taken before Gnr Dooley joined the 23rd battery in 1942. He is in the middle row 2nd from the left. |

|

This is a photo of two of the A/A guns in Sgt Dooley's album. Not sure of when and where it was taken but is believed to be from the AWM. |

I was on Harry 1 for approximately 12 months in which time I managed to get a good dose of malaria. While in hospital an ack-ack lad died and on returning to Harry 1 they thought they had seen a ghost as they were told it was me. While at Harry 1 we all joined the AIF - 23rd Heavy Ack-ack Battery. I was later sent out beyond Jackson's Airport, or 7 Mile Drome to Harry 4 and was there until one day an officer said "How long will it take you to pack and make the boat. You're on leave." "Five minutes Sir" was the answer. This was something after 12 months. I don't think anyone could describe the feeling. I made the boat. Pretty rough trip on the flat-bottomed Taroona. It was good to make Townsville and put feet on solid ground. Bernard Dooley - Anzac Day 2000 |

|

| Laura said "It took us a while to notice, but Pop is the hiding on the right behind the tree. He was a bit camera shy. This is on Tuaguba c. 1943." |

|

| Section of an arm sling signed by all members of the Ack-ack Battery. Sgt Dooley donated the sling to the Australian War Memorial. Click on the image to see an enlarged and more complete view. |

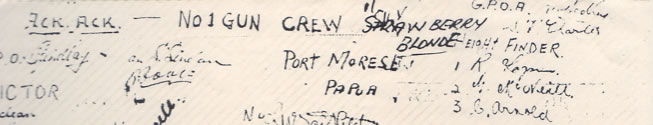

NAMES OF MEMBERS OF THE BATTERY

NO. 1 GUN |

NO. 2 GUN |

NO. 3 GUN |

NO. 4 GUN |

STRAWBERRY BLONDE |

DOROTHEA |

LEADER OF THE OPPOSITION |

THE AVENGER |

Roy W Bartlett |

D McMillan |

Robert H Porter |

D Matthews |

Bernard Dooley |

William R Booth |

B Wilson |

William Dwan |

Henry W Stevens |

Ray T McCracken |

K D Percy |

Stanley A Harris |

Peter R Cumming |

B Russell |

Albert H Plumridge |

Emil H Draeger |

John D Harry |

J Clark |

Sydney J Lynch |

P J W |

John D Jones |

Henry J Williams |

W Kinney |

Bromley R Steen |

Paul F Kent |

John D McLeod |

Lenard W Sedgeman |

Clarence McQualter |

Frederick L Taylor |

S Booth |

L McLaren |

A Dunn |

G McKenzie |

L E Watson |

Percy J Collins |

Walter Bishop |

Edward C Baker |

Ronald M Dole |

Alwyn H Robinson |

J K Fraser |

W J Smith |

Arthur F Rankin |

Edward P Bergheim |

Francis C Marshall |

Owen H Flannery |

Kenneth J H Simons |

Norman J Wishart |

Robert Montague |

Burtom Russell |

A W Wood |

Leo Lynch |

John T Monahan |

J Linklater |

|||

PREDICTOR |

OFFICERS |

HEIGHT FINDER |

TI |

Ian MacLean |

Capt Alex L Findlay |

R Logan |

Wallace McG Elliott |

Geoffrey J Neill |

Major Ian S Sinclair |

G McNeill |

H Black |

Lancelot E Panther |

Lt Arthur W Hedley |

C Arnold |

L Stoll |

J Clarke |

Sgt Stanley N Charles |

||

J Muller |

Lt Bernard A Foote |

COOKS |

|

Emil H Draeger |

WO2 Ross S Smith |

Reddick |

|

John H Gillingham |

|||

E Ryan |

|||

Kenneth W Charty |

TED PANTHER'S WAR

|

L/Bdr Ted Panther at Port Moresby 1944 |

Another of the 23 Heavy Battery gunners at Ack-Ack Hill was Lancelot Edward (Ted) Panther, born 1912 in Beaufort Victoria. Ted was from a farming family in nearby Raglan and enlisted in the CMF March 1941. He underwent training at Williamstown (Melbourne) with the 4th AA Battery and after five months was transferred to Coode Island where he trained as Specialist TG 11 (2) Predictor. From here he was sent to Port Moresby arriving 3rd January 1942 aboard the Aquatania and placed in the 23 AA Battalion for AA service at Tuaguba Hill.

Like many of the CMF men at Port Moresby Ted transferred to the AIF at the suggestion of General Blamey when he visited in March 1943. He was given a new number (VX 136127) and promoted to Lance Bombardier on 18 January 1944. Ted stayed with the AIF in Port Moresby until 2 April 1944 and returned to Australia thereafter. He was de-mobbed from Royal Park Sydney in February 1946. Ted died on 21 February 1974. [Information courtesy of his son David].

LAURIE WARD'S WAR

An oral history of the wartime service of Lawrence William Ward 1939 - 1945

This is a transcript of a voice recording made on 18 November 1997 in New South Wales Australia with Lawrence William Ward (Laurie). The interview was carried out and recorded by Tim Faulkner. Only a part of the transcript relevant to his army life in Papua and SE Asia is featured here.

|

Laurie Ward photographed outside his home in Gosford NSW - about May 1943 - after completing basic training in Dubbo. (Bruce Ward). Click image to enlarge. |

Laurie was a farm labourer born in Gosford NSW in 1922 and enlisted in the army in October 1941. He arrived for duty at the Sydney Showgrounds on 1 January 1942 and travelled to Dubbo NSW for basic training. Laurie was sent to Newcastle NSW for gunnery training and duty using the 3" - and later 3.7" - anti-aircraft guns. He was sent north and departed Townsville on 17 February 1943 arriving at Port Moresby three days later. He was placed with 23 A/A Battery but immediately transferred to 32 A/A Bty for duty at Tuaguba Hill - already known as "Ack Ack Hill". This is his story. This excerpt begins with Laurie being asked about the date of departure from Townsville for Papua.

Laurie: I think in August or early September 1942. These dates of sailing and coming home have long really escaped me, I have no recollection of dates.

Tim: And that vessel took you to Papua New Guinea?

Laurie: That vessel, which was the troopship Katoomba which had been a small pleasure liner plying the Pacific prior to the war.

Tim: How many men were on that troopship?

Laurie: I have no idea of the actual number, but it was very crowded. They had quite a few decks and we were right down on a lower deck and you just slept on the bare floor or on hammocks. You were allocated a place to sleep and swinging above you was a hammock to accommodate double the quantity of men. As we went down the stairs to that deck it had above our heads at the bottom of the stairs 'cattle deck'.

Tim: How long were you on troop ship Katoomba?

Laurie: For three days on the troop ship to go to Port Moresby. The journey normally does not take that long, but in convoys during wartime their speed is governed by the slowest ship in the convoy and we had one that could only do 4 knots. We were guarded by a warship called a corvette and overhead from daylight to dark, and it amazed me the number of hours these aircraft and crew could stand, but from daylight to dark a Catalina aircraft flew over the top, for spotting of enemy submarines. During the voyage there was a submarine scare. The Catalina circled the warship and waggled its wings. The Corvette turned around very sharply and raced slightly to the rear. And both the Catalina and the warship fired many depth charges. The result of this we will never know. We were never told any results of this action.

Tim: Would that have been an Australian Corvette?

Laurie: Yes.

Tim: And how many ships would have been in your convoy?

Laurie: About 7.

Tim: When you went overseas to New Guinea is that the first time you had been overseas?

Laurie: Yes, it was the first time I had ever been out of New South Wales.

Tim: And you were stationed then in Port Moresby?

Laurie: Yes. On arrival in Port Moresby things were very grim and serious because of enemy aircraft and the Katoomba pulled into the small jetty, but before our arrival there we had been drilled on how quickly to evacuate the ship. Before entering the harbour all troops were lined up with their full equipment on and we all doubled very smartly, which was a run, off the ship, down the gang plank, clear of the wharves, mounted what few trucks there were and we were very quickly removed from the harbour area - because of the danger of Japanese aircraft coming over. Our landing went very uneventful and thankfully there was no air raid at that particular time and the Katoomba made its turnaround safely.

|

|

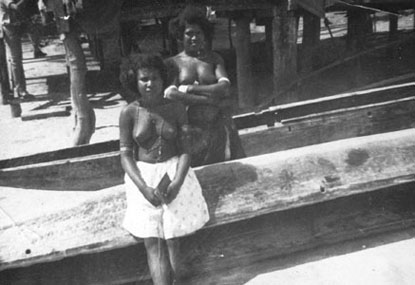

Two 32 Battery gunners with one of the locals - Port Moresby. (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

Local women at Port Moresby - 1944. (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

Tim: And then you were attached to a unit in Port Moresby?

Laurie: My unit at that time was called the 438 Heavy Ack-Ack Troop. After going to Murray Barracks, which was a staging camp. We spent one night at Murray Barracks and had our first experience of tropical rain and sleeping out in the open. Sometime through the early hours of the morning, the skies opened up and there was a absolute deluge, so we all got well and truly soaked.

|

Laurie Ward (2nd right) with his tent mates at Port Moresby. In the centre is Vincent John Quinn (grandfather of Jason Quinn). |

Next morning we were moved to our positions, our gun positions, which was a hill rising straight out of the Port Moresby village or small township. It was named then, after we had been there for a short time, ack-ack hill, but I don't know the actual real name of it, but it was a prominent hill. I think probably about 800 feet high. The top of that hill had been levelled to take our gun positions - our four guns and other equipment.

|

This painting by William Dargie from September 1942 shows the position of two 3.7 inch anti-aircraft guns on Ack Ack Hill. Men wearing shorts and tin helmets stand next the guns, while 44-gallon drums have been used to fortify the area. Camouflage netting was not used at the emplacement in 1943 or 1944. ART22249 |

Tim: How long would you have been stationed there?

Laurie: I was stationed there approximately 18 months.

Tim: From about September 1942, that would have taken you through to early 1944. Does that sound right?

Laurie: Yes.

|

| Anti-Aircraft gunners of 32 Bty Ack-Ack Hill just after an alarm that Japanese planes were in the vicinity. Photo taken of men at action stations in July 1942. Four 3.7" Heavy Anti-Aircraft Guns manufactured in Maribyrnong, Victoria were installed at this site. At one point, the battery ran out of ammunition, as it was firing nearly every day at attacking Japanese bombers. Laurie ward said "my job was to either spin the gun around to face the planes, or I'd sit on a seat [as above] and crank the handle to synchronise the pointer, actually an arrow with a hole, on the dot on the card". AWM025623. |

Tim: You would have seen a few air raids in that time.

Laurie: Quite a lot of air raids because the Japanese had complete control of the air. We had no fighters and very very few bombers. Our fighters having been shot down in the Darwin region in the early part of the New Guinea campaign, and up around Rabul. The Japanese having air supremacy just came and went at will.

Tim: And it was your job to shoot them down?

Laurie: Yes, our job was to protect both the harbour of Port Moresby and the then airfields, which were Ward's and Jackson airstrips.

|

|

Japanese Zero captured by RAAF. (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

At Camp. (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

Tim: Did you ever manage to shoot down any Japanese planes?

Laurie: The purpose of heavy ack-ack is not actually to shoot down planes, it is to keep the area above the target area very bumpy so the bomb aimer cannot take accurate aim on any target. These huge shells exploding create a turbulence in the air. But the air force did accredit us with having shot down 68 planes. Now we didn't actually see these planes - no plane plummeted to the earth like you see on the movies. The shrapnel from these shells pierced fuel lines or fuel tanks and the bombers used to go out with a trail of smoke behind them. People knew they were going to crash into the Owen Stanleys, because they couldn't climb to the altitude to get back over.

Tim: How did you feel when the air raids were taking place, did you find it frightening?

Laurie: One thing I must remark about military training, you are trained to such a degree that when action does occur, I guess for the first few seconds and the first few minutes there is that apprehensive feeling of not knowing what is going to happen, but from the time the first shot is fired you are all engrossed in carrying out the duties that you have been so highly trained to perform.

Tim: Was your position ever attacked by enemy planes?

Laurie: We were a great source of annoyance to the Japanese aircraft and they sent over dive bombers and fighters at various times to try to eradicate us but they were unsuccessful, never did us any real damage on any occasions. The bombers, after having crossed across the target area, which was the airfields, would go out to sea and circle and make their return run and they would drop any bombs they had left on the harbour or on us, which the two were varied only a few degrees on the difference in their bearing and several times strings of bombs were let loose at us from high level bombers, but very fortunately these missed.

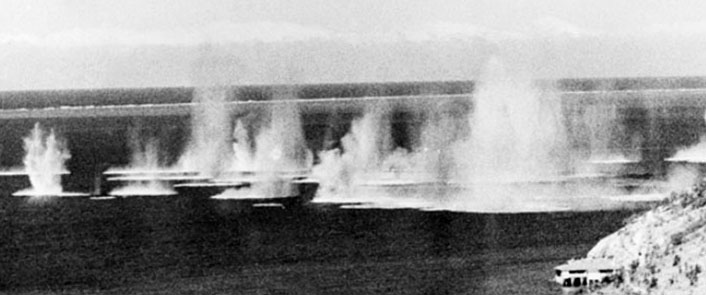

|

| Japanese raid (No. 73) on Port Moresby 24 July 1942. Bombs are seen bursting off Paga Point - with the Officers' Club not too far away (bottom right). The Japanese would fly south from their base at Lae or Rabaul. As Laurie said in the paragraph above, sometimes after bombing the Bomana Airport they would go out to sea and circle around again dropping bombs on the Ack-Ack position before returning home. Judging by the splash heights, this may have been one of those ocassions. AWM |

Tim: Did you ever see casualties while you were at Port Moresby?

Laurie: We had one of our crew slightly wounded, strangely enough not by the enemy action, but by the shrapnel falling from our own guns.

Tim: Was that a serious wound?

Laurie: No it was just a flesh wound on the arm.

|

|

PNG or Moratai - 1944 (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

"Alex Bailey and Co." Laurie Ward |

Tim: Did the enemy planes cause a lot of damage to the harbour and the shipping?

Laurie: There was one ship lying wrecked in Port Moresby Harbour. The procedure was as soon as an air raid was imminent, the ships used to untie or up anchor and clear out to sea and manoeuvre out at sea. There were ammunition dumps and aircraft damaged around the airfields. We would see huge plumes of smoke go up where dumps had been hit by bombs.

Tim: Whilst you were serving in Port Moresby did you have much information about what was happening further inland?

Laurie: We did, but it was very slow in coming back. When we were initially there, the KokodaTrail/KokodaTrack episode started. First of all our Australian Military Forces, which were as I mentioned were home defence, went in, up the KokodaTrack to meet the Japanese advance. They were badly mauled, beaten because of the Japanese superiority in numbers and experience. Now a unit of our 7th Division, the 25th Brigade arrived in Port Moresby and went straight forward into the KokodaTrack. Information used to drift back by way of the wounded coming back to hospital of what was happening on the KokodaTrack. These men were short of food, ammunition, and every kind of supply that you could imagine, and they put up an epic struggle to finally drive the Japanese back after initially retreating.

But Tim, I must clarify about my time in Port Moresby - I said that I was on Ack-ack Hill. That was initially the case, but later on, some six months later on, as we were experienced troops, we were sent out to various other new units that were arriving and for quite a while I was stationed near the American docks, which was built during my period there further up Port Moresby Harbour. [There is a note on his War Record for August that said he may be authorised to train others. Laurie recalls being posted with the American base for a time, helping train the new crews on the guns defending the American dockyards.]

Tim: And that would have also anti-aircraft?

Laurie: That was also heavy ack-ack.

|

3.7" Gun at Ack Ack Hill being dismantled in 1944 (courtesy Laurie Ward)

|

|

Dismantling "Harry 1" - a 3.7" gun on Ack Hill - 1944. This battery was manned into late 1943, until the threat of air raids had sufficiently passed. (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

Tim: Just going back to the KokodaTrail, did you think the Japanese were close to Port Moresby?

Laurie: We were well aware just how close the Japanese were, and in fact, all base troops were very much on the alert for Japanese patrols landing and being infiltrated by, I guess Japanese spies, such as natives, who were friendly to the Japanese. But all our infantry training was kept up so that we could fill in a role in the defence if the Japanese did succeed in pushing our troops back over the Owen Stanleys.

Tim: Were you afraid about the Japanese coming into Port Moresby?

Laurie: We were very apprehensive about it, being cut off from Australia, and they were terribly dark days, because the Japanese had never been defeated, they had air supremacy and as far as we knew, they had naval supremacy. It was shortly after that, the Battle of the Coral Sea, that the first naval victory took place. We, on the ground, were witness to this great event in that as the aircraft going out to bomb this Japanese fleet, we would count the aircraft going out and count them coming back in and knew of the allied losses. And the aircraft that did come back were so peppered with shell holes you that could almost see through them. These planes touched down, refuelled, rearmed and went straight out again.

Tim: Would these mainly have been American planes?

Laurie: No by that time the Australian Air Force was there and strangely enough it was during this period that they mixed the Australian and American crews. So there were Australians flying in the American aircraft and vice versa, Americans flying in the Australian bombers.

Tim: So these would have been Australian bombers flying from Port Moresby to take part in the Battle of the Coral Sea?

Laurie: Yes.

Tim: You said that when you first arrived in Port Moresby and came ashore from the troop ship, the Japanese had complete air superiority, eventually though you would have started to see allied fighters back in the sky. Do you remember when they started to return?

Laurie: I am not certain of the date, but I saw on a documentary that I think it was 77 squadron arrived with Kittyhawks. We'd heard about these Kityhawks for many months and had been waiting with anticipation for their arrival.

Tim: That would have been a unit of the Royal Australian Air Force?

Laurie: Air Force yes. And I think their actual stay in Port Moresby was 40 days in which time they did massive damage to Japanese aircraft, mainly on the ground over at Lae and in the vicinity of the enemy airstrips. They struck very early in the morning and wiped out - morning after morning - wiped out many aircraft.

Tim: And they only stayed 40 days?

Laurie: They were wiped out after 40 days of fighting. They were the only aircraft - fighter aircraft - and they intercepted all enemy aircraft coming in over Port Moresby. They went out and intercepted them and had dogfights.

Tim: Did you see any of that?

Laurie: No, we were well… - Yes we did see a little of it, mainly they did their intercepting before the aircraft reached target area and after the aircraft went out to sea, they would strike them out there again. But what was termed target area was left for the guns to control.

Tim: So that you would not shoot down your own planes?

Laurie: Yes. One American fighter did come in over target area and we had to quickly cease firing while he was in our range, and he was severely reprimanded and grounded for some months for violating regulations.

Tim: Were there ever any American fighters in the sky over Port Moresby?

Laurie: Yes, after 77 squadron, both air force, army, and navy had a huge build-up and the American planes started to arrive in huge numbers. But I can't tell you exactly what month that was.

Tim: And they would have made a difference, a big difference.

Laurie: Yes. But it was the 77 Squadron that seemed to have made a big hole in the Japanese aircraft.

Tim: How did you get information about what was going on in other places in the war, apart from Papua New Guinea, like what was happening in Russia and North Africa?

Laurie: Communication during the war was very very slow and if I may say so, pretty poor. Troops in general only heard by rumour or in New Guinea, some enterprising young men set up a very small newspaper. I guess the sheets were about 9 inches by 8 inches and the newspaper would consist of 4, sometimes 6 pages. And world events such as the British South-East Fleet shelling the islands of Japan, would appear in such a small little column. Mainly the news we got was American news, we got very little about what was happening in the Europe theatre of war or the Burma theatre of war.

Tim: So that was your only source of information?

Laurie: Apart from what came through by word of mouth.

Tim: In February 1942, which would have been just after you joined up, and probably while you were still in Australia, Singapore fell to the Japanese. Obviously you would have heard about that?

Laurie: That was a huge blow, both to morale, because Singapore was the fortress island, impossible to be conquered, and for that to fall was like a huge black cloud passing over Australia.

Tim: How did you hear about the fall of Singapore?

Laurie: I am not quite certain, but I think possibly we were told on parade, which we were about some of these big moments.

Tim: Do you remember the Prince of Wales being sunk by the Japanese? It happened in December 1941.

Laurie: Yes. I remember that news coming through and once again this seemed so incredible that such a mighty battleship would go down in what would seem to be so easily.

Tim: Do you remember whether there was ever a time when you thought that the allies would lose the war?

Laurie: Once again, I don't think that thought ever came into my head, but about this period, about the time that Singapore fell, I think a lot of us were very fearful that we would be fighting the war here on Australian soil.

Tim: Also in December 1941 the Japanese attacked the American Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbour and the Americans then entered the war against the Japanese. Obviously you would have heard about that event.

Laurie: Yes, once again that was shock-horror that they could be taken by such complete surprise and so much damage done.

Tim: Were you pleased though that the Americans had now become involved?

Laurie: I have no recollection of my thoughts at that time apart from the shock at the disaster.

Tim: Do you remember when you first met some Americans?

Laurie: Yes I first met American forces in Townsville, and they were there in quite big numbers at that stage. I guess they were once again possibly base troops, because when we got to New Guinea there was just the odd unit there and they seemed to have been units with pack mules and pack horses and training them for warfare and the New Guinea campaign. But the conditions proved too harsh for the animals, so that was a failure.

Tim: How did you find the Americans?

Laurie: Quite a surprise at their brashness and boldness, and they thought they could buy everything with money. They talked about two and three car families and to us Australians where cars were just a dream, and most families didn't even own a car, it just seemed so unreal that a family could be so rich they could own 3 cars. The American negros eventually came to camp alongside us in Port Moresby, near the American docks and we found them very helpful and we had a lot of amusement out of their antics. They were great troops to be camped along side of.

Tim: Were the Americans generally good soldiers?

Laurie: It is very difficult to answer that question Tim, because you can't brand everyone with the one brush. The initial troops in New Guinea weren't perhaps well led and they had many setbacks. Around about Buna, which was over the Owen Stanley Ranges, Buna and Gona, American troops, infantry, were sent to relieve or to support Australian infantry and on the areas where they had gone in and relieved they immediately lost the positions that the Australians had gained and their early part of the New Guinea campaign wasn't a success.

Tim: Let me just ask you briefly about something else. In October 1942, the battle of El Alamein took place in North Africa and the British 8th Army, including the Australian Divisions dealt a deciding blow to the Germans in North Africa. Were you told about that particular incident?

Laurie: Yes, we heard about that and I can't imagine at this stage how long afterwards we were told officially about the El Alamein battle and the 8th Army's victory and about the Australian 9th Division's part in that. I believe that they were the spearhead of that attack and it caused me some great concern because my eldest brother was with that unit. And we had no idea of his health at that stage - or his wellbeing I guess.

|

"Harry 1" - a 3.7" gun at Ack Ack Hill being dismantled - Port Moresby, 1944. Laurie Ward was one of a "tail party" left to disassemble all the guns - grease them and pack them up for shipping back to Australia at the end of the war. The summit of Ack-Ack hill has been largely untouched since the war. Metal 44-gallon drums used to form revetments are still present, and depressions for smaller gun pits and the concrete bunker at the center of the battery are still visible. (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

Tim: After you had been in Port Moresby until say early 1944, where did you go then?

Laurie: Briefly just to... - while in Port Moresby I had what is called peritonitis [this was appendicitis, which after the appendix ruptured, became peritonitis]. I was taken is stages to the 2/1st Australian General Hospital [AGH], which was just setting up its tents... - hospital had just returned from the middle east theatre of war. I was their first patient and the doctor operated on me immediately. Before I got to the 2/1st AGH, the Medical Officer that I had seen at a casualty clearing station gave me the option of going forward and having it out, or going back to my unit, but his description of it was that next time I mightn't be in a position where I could get out, and I was a lucky boy to still be alive that morning. So I went to the 1st AGH and was their first patient and looked after like royalty.

Tim: Where was that located?

Laurie: That was on the sea-side, the ocean side of Port Moresby.

After having had the operation, I went to a convalescent camp up on the foothills of the Owen Stanley Ranges and while there, because of the resistance being lowered I contracted dysentery and was sent back from there to the 2/9th AGH to a special dysentery unit, which was filled with lots of troops with that complaint.

Shortly after getting over dysentery I was sent to a staging unit and while at the staging unit, we were going out loading aircraft with supplies, both food, ammunition, first aid etc. These were American DC2s and DC3s and in charge of the work party I was consigned to was a sergeant from the 2/1st Engineers Battalion [actually Pioneer Battalion, correct in later references] and he was a mortar sergeant. Having been trained in mortars early in my infantry training during the course I talk I said that I had been trained in mortars and little did I know that would lead me on a different route for a few weeks.

He was to fly back to his unit within the next couple of days and he found out on enquiring that they were very short of troops. So I was seconded to fly with him to a place - and airstrip called Tsili Tsili where his unit had just landed and from there we made many trips from there to the plantation on the banks of the Markham river, carrying supplies and bridging materials for crossing that river, and was a combined operation between the Australians and the Americans to take an airfield on the opposite side of the Markham River. We, after carrying all the supplies hid in the vicinity of the plantation waiting for the weather to clear for the paratroop landing. Finally after about 5 days of hiding, the weather cleared and the signal was given. The Americans dropped their parachutes - the first parachute landing by the American troops of the Pacific war. Simultaneously we crossed the Markham River and advanced from the side of the airfield. The airfield name escapes me at this moment. [The airfield was at Nadzab.]

It was a fairly uneventful action as there was very little resistance. It had taken the Japanese completely by surprise. Once we had, and I say the Americans and ourselves, the battalion I was with, had cleared the - secured the airport - we all set top to clear it of kuni grass to slash it and burn it for incoming aircraft. By that afternoon those aircraft were arriving and a massive build-up took place and units of the 7th Division arrived and once more the 25th Brigade - I mention this because later I became a member of that Brigade. This build-up took place and a week later the advance up what became known as the Lae Track took place. We advanced with the 25th Brigade up this track and was in support of or in action with B Company of the 2/33rd Battalion on several occasions. I was with this 2/1st Pioneer Battalion on loan as a mortar man, so I was with the mortar section of that unit.

Tim: And was that action the last action you had in Papua New Guinea?

Laurie: After the fall of Lae, all troops returned to this said airstrip, in other words we retraced our steps. I had another bout of dysentery and was flown back to Port Moresby. Thankfully this was very brief - I also had malaria at the same time. At this stage they weren't flying troops back, but seeing that I had malaria and dysentery. I went back briefly to the 2/9th AGH and then back to my unit in Port Moresby, which was packed up and ready to return to Australia. And I along with 9 or 10 others drew the lucky straw to remain with the unit equipment.

Tim: In Port Moresby?

Laurie: In Port Moresby, and unbeknown to us the boat arrived duly, about a week after the rest of the unit had left, to take our equipment - our big guns and unit equipment, but it had no room for us, it only took one of our members with it as a caretaker of the unit's equipment. The rest of us remained there and became like lost sheep. As far as records were concerned we were home in Australia, so we had no food rations or supplies. We got onto the end of any mess queue we saw forming at any unit and mostly we could sneak right through, but at other times the troops would sing out loudly that we were stealing their food, so it became quite embarrassing at times. Finally a young lieutenant came over to see what the argument was about and thankfully took charge of us and got us a boat home. But we were there some six weeks after our unit returned.

Tim: And when you went back to Australia whereabouts in Australia did you go to?

Laurie: We landed in Townsville, I can't remember which ship we were on - we landed in Townsville, went to a staging camp there and were issued with a rail pass - no I am sorry, eventually put on a troop train and sent back to Brisbane.

[snip]

Tim: And then you were shipped abroad again?

Laurie: We went almost immediately to Townsville where we one again boarded troop ships and we knew not where our destination was. The rumour was that we were going to join the American landing in the Phillipines.

We went to an island called - a harbour called - Moratai and I feel this island is in what was called the Celebrities group of islands. They have been changed I believe.

Tim: And you went there straight from Townsville?

Laurie: Straight from Townsville our convoy went there. The Americans had taken a portion of the island, the portion that they needed and the Japanese were still pushed up at the other end of the island.

As soon as we arrived there units of the 7th Division were given the job of manning the line, the defence line, between the American base and the Japanese that had been pushed back.

Tim: Did that include your unit?

Laurie: Our unit did 10 days there in its turn. During the term there on the perimeter you were sent out on patrols to patrol the vicinity of the line to make sure the Japanese - keep an eye on the Japanese to see what their intentions were.

Tim: Did you have any contact with the Japanese while you were up in the perimeter?

Laurie: Several Japanese marines came in and one Japanese nurse. They were on the point of starvation, they were skeletons. The Japanese nurse was I think 6 or 7 months pregnant and weighed about 5 stone.

Tim: They came in to surrender did they?

Laurie: They came in to surrender, yes.

Tim: So did you get the feeling that the Japanese on the island were in a fairly poor condition generally?

Laurie: Yes, they had no rations and I guess very little supplies of any sort.

Tim: So did they give you any trouble?

Laurie: They didn't give us any trouble. They fired on a few of the American boats that went around their end of the island, fishing and doing things for pleasure, which was very stupid. They fired on a few of those.

Tim: When would this have been?

Laurie: This was in 1945,

Tim: So early 1945?

Laurie: Yes, I think.

From Moratai, we boarded landing craft. There was a huge build up at Moratai, both American and Australian personnel of both air force, naval - naval ships were just bristling everywhere. We boarded landing craft. Before boarding we had to load them with the supplies for landing. And we set forth and our destination, so we were told once we had put to sea, was Balikpapan in Borneo, which was an oil - rich in oil - and had many oil refineries around it. Our task was to take the oilfields at Balikpapan.

|

|

Tropical beach possibly at Moratai - a northern island of Indonesia. (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

Native children in Morati - 1944. (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

Tim: How long would you have been on the landing craft once you set sail?

Laurie: We were approximately 5 days on the landing craft. Not all of this was straight sailing. At times we were virtually stationary or moving very slowly, and I guess this was all to coordinate the fleet and everything that was involved.

Tim: Were these open landing craft or was it a big ship with small landing craft that went away from it?

Laurie: No it was an open air landing craft, you were exposed to the weather.

Tim: For 5 days?

Laurie: For 5 days.

Tim: Before you landed?

Laurie: Before we landed. We - the 25 Brigade was considered - had had a lot of action during the war and they were going to be rested in this campaign, so they were left on board the landing craft, sitting slightly out to sea, witnessing the landing of the other 2 brigades of the 7th Division. The naval and air force bombardment was horrendous, apart from the destroyers and medium types of warships, that were in our vicinity shelling the shore and inland, there seemed to be big battleships way out to sea booming away. We thought it was one of the British 'battle wagons' as we called them, but on talking to naval personnel since the war, they said no, there was no battle wagon in that vicinity at that time, it must have been a heavy cruiser.

Tim: And they were shelling the island where you were about to land?

Laurie: Yes. As the infantry go into one of these landings, there had been underwater crews that had gone in and cleared all underwater defences from the beaches. As the infantry go in the barrage moves further inland, in other words 'lifts'. The infantry go in and secure a foothold and as soon as there are enough troops assembled they push back from the beach as rapidly as they can to get off the beach.

The 2 brigades that landed, one was to go more or less directly inland and the other one was to take the coastal strip - take the air strips along the coastal strip. The second day after the landing, we were very quickly landed because the Japanese were coming down in between the two spearheads that were attacking, the one inland and the one up the coast. They were quickly advancing down the middle of these two. We were quickly landed and raced up the middle of these, what became known as the 'Vassey highway'. It was a road, not really a highway, and we advanced fairly quickly up until we met the Japanese, and the opposition was quite stiff. There was lots of medium sized hills of various heights and they had all of these. They were quite steep and very very well fortified. It took quite a bit of dislodging from these peaks.

Tim: Did your company go into action?

Laurie: We were into action quite a lot there. Sometimes, in our turn, we were forward company. Other times we were perhaps on a wing position, which meant a supporting position. Other times we were pulled back a little bit to have a breather. But during these breathers we patrolled quite heavily.

Tim: So you would have had direct contact with the Japanese, you would have personally had direct contact with them?

Laurie: Yes.

|

|

US Cemetary Morati. (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

Moratai - 1944. (courtesy Laurie Ward) |

Tim: And did your unit suffer many casualties?

Laurie: We suffered quite a lot of casualties there - when I say quite a lot, a fair amount, because as I said, these positions were very steep and very well defended. There were quite a few decorations given out to members of the 7th Division for that campaign.

Tim: Would this have been the first time you had shot at Japanese with small arms?

Laurie: No because I had been engaged along the Lae track. Now B Company of the 2/1st Pioneers who I had been attached to had been in support of B Company of the 2/33rd on several occasions, and I had seen action there.

Tim: And was the action in Borneo successful, did you push back the Japanese?

Laurie: Yes, and the remarkable thing about the action there was the more support that we had. Never had we had such naval support, air force support and artillery support, because of the better roads, the artillery and tanks could move with us; we had never had this in New Guinea. If a position proved to be too heavily fortified we were always ordered to withdraw and naval and air force support was called in to plaster. And in most instances after a plasting, the Japanese would withdraw, not all occasions. The unit attacking would go straight in after a barrage, a plastering, a unit would go straight in and try to take the fixture.

Tim: So you were engaged with the Japanese at Balikpapan when the war ended?

Laurie: Yes, just prior to the end of the war, or the ceasefire being announced, there seemed to be an unusual calm over the frontline situation. Patrolling continued but there was no… At the end of this calm period rumour spread like wildfire through all the lines that the Japanese had surrendered. There was no official announcement and this first rumour that spread through proved to be false. I think approximately 7 days later - during the 7 days patrolling continued very strongly and approximately 7 days later the official announcement came trough of the ceasefire - that the Japanese surrendered.

Tim: Do you remember precisely where you were when you heard that?

Laurie: Yes, we were in a forward position along the Vassey Highway. Patrolling continued for quite some time, I think perhaps 2 weeks, I am not quite clear on this, but some time, then gradually the Japanese troops started to file through and surrender. There were pockets, not in our area, where they completely disbelieved that Tokyo had surrendered and refused to lay down their arms, but this didn't happen in our sector, in the Balikpapan sector.

After the Japanese had surrendered, we were withdrawn down to the beach at Balikpapan, and this proved to be paradise. We set up a regular army camp, pitched tents and did all that type of thing. We only had one parade a day at I think perhaps 8 o'clock in the morning, we had a battalion parade, the orders for the day were given, that just meant carrying out ordinary regimental duties such as guard for the camp area. We were at liberty to do what we liked - we surfed, it was a beautiful, I say surfing area, it was inside the coral reefs, just moderate waves, but it was golden sands and just an idyllic spot. We played in the water and swum and did everything that you do at the seaside. We really had a ball.

Perhaps two weeks down the road, at parade we were ordered to make ourselves bathing trunks as a lot of the people coming back from concentration and prisoner of war camps were women, mainly Dutch women. So we were ordered to make bathing trunks and make ourselves respectable. Up until then we had swum in the nude. The only material we could get to make bathing trunks out of was sugar bags, which are hessian bags, or flour bags, but the sugar bags were finer hessian, so we scrounged, by fair means or foul, sugar bags and cut ourselves out and sewed swimming trunks for ourselves.

But the scream of the whole situation was they put up hessian barricades for men and women to get undressed in, but when the men went inside this enclosure to put on their swimmers or get dressed, the Dutch women walked up and leant on it and talked to them! And the Dutch women, being European, either swam in the nude, or put on their swimmers standing on the beach - they got completely undressed. So the ridiculous situation was we were made cover up, but the women we were protecting, so we didn't disgust them, were completely the opposite.

Tim: How long were you in camp in this paradise situation?

Laurie: Just about from the time we arrived there we started to whinge and moan about getting home. We were in paradise, but didn't really like it, we wanted to get back home to Australia.

The forces were split up and sent all round to all points of the compass to take the Japanese surrender. I was sent to a town around the south-western coast of Borneo - a city I think of 30,000 Chinese and 35,000 Malays, called Pontianak. We boarded at Balikpapan Harbour the frigate HMAS Barcoo, which incidentally sunk in a gale in South Australian waters a couple of years after the war.

On this frigate, we went around the south-west coast of Borneo. I took us roughly a day to get there. We dropped anchor off shore and Chinese lighters came out, these were in the form of a barge, came out to take us ashore. I don't know how all this had been prearranged, but they came out, they had to come outside the coral reef because the Barcoo couldn't go in. We boarded that and there was a party of about platoon strength, which is 12 to 15 men, with a lieutenant in charge. We went in two lighters to the shore at Pontianak. They had small jetties, and we climbed up on the jetties and formed up in the vicinity of the jetties into marching order, and with the lieutenant in the lead, we marched right through the centre of Pontianak, which had just one narrow tar road and not very long. And I say a city, it had just a few shops, but a city by the mass of population. We marched down and we took the Japanese surrender - they were lined up somewhere in the centre of the city and the Japanese officer-in-charge came forward and passed his sword over to our lieutenant and then the remainder of the Japanese came forward and laid their rifles on this tarred road.

TUAGUBA "ACK ACK" HILL TODAY

Photos and captions courtesy of Kell Nielsen.

|

The location of the A/A gun emplacement is shown by the red dot on Tuaguba Hill. It has a commanding view of Port Moresby Harbour and the rich people with their playthings at the Yacht Club. |

.jpg) |

| This photo was taken from the south-east side of the emplacement looking out over Port Moresby Harbour. Above the left pair of bolts is Napa Napa and the newly built oil refinery. To the right is Tatana Island. Between Tatana and the emplacement lies the MV MacDhui, sunk by Japanese bombers in June 1942 and rolled over on the coral reef. She is not quite visible in this picture. |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

This photo shows the bolts used to hold down and level the gun.The 40 mm bolts were cemented into the concrete floor/slab during the pour. There were very large nuts with notches in them so a special tool could be used to raise or lower the nuts and thereby levelling the gun. |

Taken from inside the one of the main Ack Ack bunkers looking NW. Burns Peak can be see just behind the tree. The triangular cut through the mountain was made by Curtain Brothers so the new Poreporena Freeway could be built directly to The Papua New Guinea National Parliament building, Boroka and Jacksons Airport. |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

| Anciliary gun pits were constructed on the outside of the main emplacements and were for use by Lewis machine guns and a Bofors gun. The structure in the centre is believed to be one of these anciliary gun pits. | Taken from the gun emplacement on Ack Ack Hill. On the right is the 'Royal Papuan Yacht Club' Club House down on the banks of the Harbour with Hanuabada just behind it. Only one of the Marina Jettys can be seen. To the right of RPYC is a massive reclamation job going on. |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

The gun pits were constructed out of two layers of 44 gallon drums with the tops cut out. The area of the gun pit was levelled by hand and the drums placed in position and filled with local rock. The drums provided an excellent barrier against bomb splinters from the outside. Today the rocks inside these remaining drums look like washed river rocks. But that is only due to 60 years of washing and flushing by rain. Sadly, if the developers don't destroy these sites, they will probably not last more than 10 years anyway. |

According to Laurie Ward fuel drums supplied early in the war (like the one shown above) were heavily galvanised. Later supplies of fuel came in lighter non-galvanised drums. You can see the difference in corrosion between the two types. He said the men would just cut the tops out of the drums with a cold-chisel and a hammer. |

.jpg) |

This photo shows the bolt pattern for the mounting the QF 3.7 inch Vickers A/A Gun.The concrete floor is more than 20'' thick and the bolts are set right through it. Each of the eight bolts has an adjustable nut as seen in the photo. The 9 ton gun with a thick steel plate at the base was lowered onto the bolts lining up the holes in the plate. Then it was just a matter of adjusting the lower bolts to make gun vertical (using a plumb-bob) and securing it with nuts on the top of the plate until it was steadfast. For a 5.25" or a 6" gun - as were mounted at Basilisk Battery and Paga Hill respectively, the levelling ring was 5" thick steel. The gap between the underside of the plate and the top of floor was filled with a sand and cement mix. Kell Nielsen said that when he was installing the 30 meter high light towers on the Container Wharf Site in Port Moresby Harbour in 1970s, this same system was used. |

"ACK ACK HILL BRINGS DOWN JAPS"

This article by Geoffrey Hutton first appeared in The Argus, 22 August 1942. Hutton was assigned to General HQ in Melbourne as a correspondent and then as a field correspondent in Townsville. He relieved George Johnston in Port Moresby in August 1942 where he wrote the following article. He reported fighting in Papua before covering allied offensives in New Guinea. Geoffrey Hutton was Mentioned in Despatches for his reporting of the P & NG campaign [Australian Dictionary of Biography]. The photos in this article were not a part of the original but have been added to illustrate the text.

ACK ACK HILL BRINGS DOWN JAPS |

.jpg)

.jpg)